Three massive volcanic eruptions led astronomers to speculate that these presumed rare outbursts were much more common than previously thought. Now, an image from the Gemini Observatory captures what is one of the brightest volcanoes ever seen in our Solar System.

"We typically expect one huge outburst every one or two years, and they're usually not this bright," said lead author Imke de Pater from the University of California, Berkeley, in a press release. In fact, only 13 large eruptions were observed between 1978 and 2006. "Here we had three extremely bright outbursts, which suggest that if we looked more frequently we might see many more of them on Io."

De Pater discovered the first two eruptions on August 15, 2013, from the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. The brightest was calculated to have produced a 50 square-mile, 30-feet thick lava flow, while the other produced flows covering 120 square miles. Both were nearly gone when imaged days later.

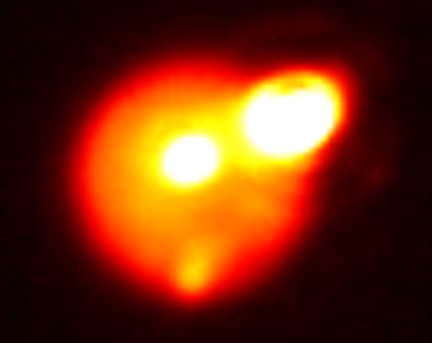

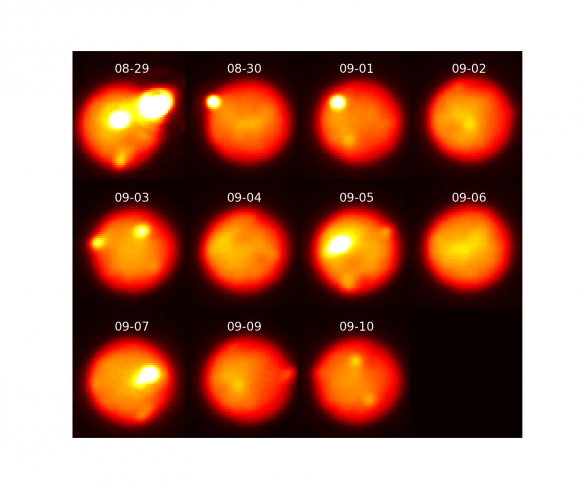

The third and even brighter eruption was discovered on August 29, 2013, at the Gemini observatory by UC Berkeley graduate student Katherine de Kleer. It was the first of a series of observations monitoring Io.

This allowed the observations to "represent the best day-by-day coverage of such an eruption," said de Kleer. The team was able to conclude that the energy emitted from the late-August eruption was about 20 Terawatts, and expelled many cubic kilometers of lava.

"At the time we observed the event, an area of newly-exposed lava on the order of tens of square kilometers was visible," said de Kleer. "We believe that it erupted in fountains from long fissures on Io's surface, which were over ten-thousand-times more powerful than the lava fountains during the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajokull, Iceland, for example."

The team hopes that monitoring Io's surface annually will reveal the style of volcanic eruptions on the moon, the composition of the magma, and the spatial distribution of the heat flows. The eruptions may also shed light on an early Earth, when heat from the decay of radioactive elements - as opposed to the tidal forces influencing Io - created exotic, high-temperature lavas.

"We are using Io as a volcanic laboratory, where we can look back into the past of the terrestrial planets to get a better understanding of how these large eruptions took place, and how fast and how long they lasted," said coauthor Ashley Davies.

The latest results have been published in the journal Icarus.

Why is IO volcanic? Most sources say because of gravitational pull of Jupiter and its large moons Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Can the strong radiation coming from Jupiter have a play in IO's volcanism? (JMCanney)

Also there is plasma dynamics, electric discharge, double-layer plasma sheaths, these phenomena apply at planetary scale described in this excellent book:

[Link]

[Link]

[Link]

"The volcanic activity contributes sulfur and other ions to the charged particle field around Jupiter, interacting with its strong magnetic field. These charged particles are swept around the planet and form a donut-shaped region called the Io plasma torus. "

[Link]

Who are we to believe?

Io is only slightly further away from Jupiter than our Moon is away from Earth. But since Jupiter has 317 times the mass of Earth, the gravitational pull the little moon Io experiences is roughly 250 times stronger than for our Moon. You can calculate this if you look at the force of gravity between two bodies:

F = G*m*M/r^2

Since the mass M is 317 times larger, and r_Io=421000km is only slightly larger than r_Moon=384000km, you get 317*(384000/421000)^2=263 times stronger gravitational forces on the same mass m.

Io has 1.5% of the mass of Earth, our moon is 1.23%... so Io and the Moon are very similar, especially since they are almost the same size and density, too.

As you can see, Earth's gravity was enough to deform the Moon so that its center of mass has moved towards Earth and it has been tidal locked. On Io, the same effect deposits so much energy that the interior stays molten. It is like as if Jupiter is kneading a giant loaf of lava.

The whole story is a bit more complex than what I told you because Io has an orbital resonance with Ganymede and Europa, which keeps the moon in a non-circular orbit at a constant distance. Without it, the tidal forces would slowly make the orbit circular, resulting in a much lower heat generation: