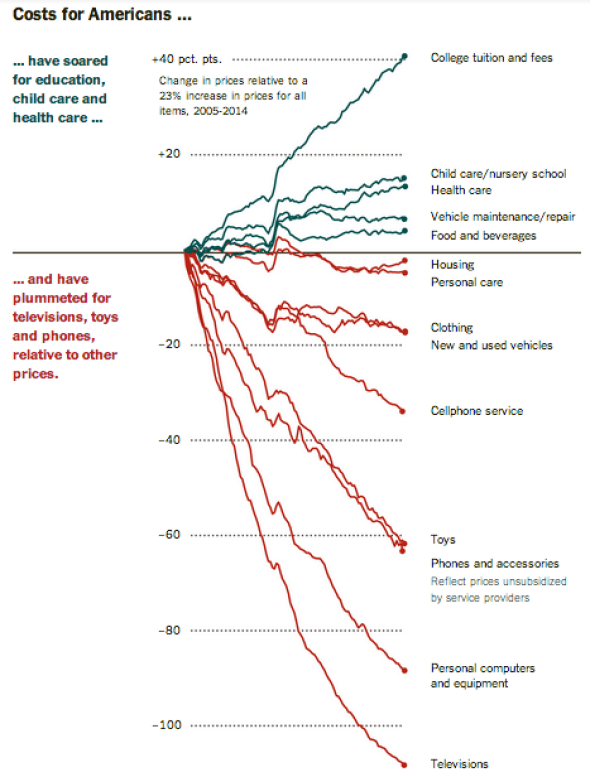

At the same time, some essentials are receding from the poor's reach. Education, health care, and child care, I probably don't need to tell you, are all becoming more expensive by the year.

This is the tension at the core of modern impoverishment, which Annie Lowrey takes on in the New York Times today. The wonders of globalization, modern manufacturing, and ruthless Walmart-style supply-chain management have made the stuff we buy to fill our homes and time much cheaper, and as a result the poor now enjoy a level of material well-being that would have seemed unimaginable decades ago. The safety net is also infinitely more generous compared with the early 1960s, before Lyndon Johnson launched his war on poverty. Yet, because the prices of key services are spiraling out of control, the poor's lot is still rather hopeless. The NYT captures it in this very, very long graph.

Here's what makes this trend so treacherous: Prices are rising on the very things that are essential for climbing out of poverty. A college education has become a necessary passport to financial stability. It's hard to hold a job if you're chronically ill. Working full-time is difficult if you can't pay somebody to watch your child. While a high-definition television is nice, it won't permanently improve your circumstances. And psychology has told us that the stress of financial instability, of not knowing whether you'll be able to pay your next bill or get enough hours at work, is part of what makes poverty such a horrible experience. Humans also tend to judge their experiences relative to their immediate surroundings, so the fact that the poor are materially better off than during the Carter era doesn't offer them much personal solace.

Lowrey doesn't address that point explicitly, but she does offer some telling anecdotes. Take this nugget, about the challenge of child care:

Tiffany Beroid, a 29-year-old mother who works at a Walmart in Laurel, Md., said she works part time, rather than full time, because she and her husband could not otherwise afford child care. Their incomes already suffered when her doctors told her to stay off her feet during the late stages of her pregnancy, and she said Walmart would not accommodate her with a desk job.Of course, the government provides help with some of these essentials. Medicaid isn't particularly generous or easily available in every state, but thanks to health care reform, it's become more so in much of the country. There are Pell grants and financial aid available to needy kids who want to attend college. The TANF program - aka post-Clinton welfare - provides child care to help single mothers get to work. But none of that changes the fact that, fundamentally, the economy is moving in a direction that will leave the poor in a deeper hole. Decency says we should help dig them out of it.

Comment: This affects not only the poor, but also the middle class, for whom college education for their children and housing in many markets is becoming increasingly out of reach. As far as retirement goes, jobs with pensions are increasingly a thing of the past.