This strange flickering, known as earthquake lights, can occur before or during quakes. Recent findings suggest earthquake lights seem to happen at rifts where pieces of the Earth are pulling apart from each other.

Normal lightning results from the buildup of electrical charge in clouds. However, lab experiments now suggest earthquake lights may instead originate from the buildup of electrical charge in the ground surrounding geological faults.

'Improbable' effects

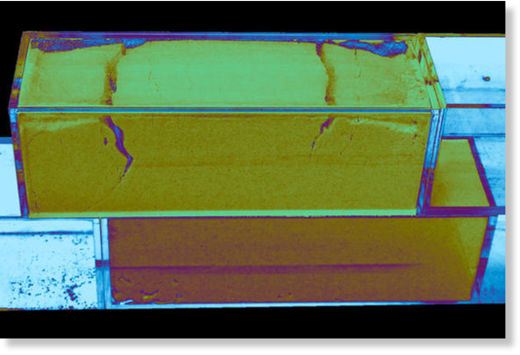

Applied physicist Troy Shinbrot, of Rutgers University in New Jersey, and his colleagues looked at three different kinds of particles - plastic disks, glass particles and organic powders, such as flour - that stick and slip in much the same way the Earth does in earthquake zones. He and his colleagues studyelectric charge in powders, which, for example, can make pharmaceutical mixtures separate or stick to surfaces in unwanted ways in factories.

The researchers discovered these different systems all developed an electrical voltage when physically disturbed, though there is currently no known physical mechanism for exactly how they do this.

"If you take a Tupperware container filled with flour and tip the container, when the flour shifts, voltages of around 100 volts inexplicably appear," Shinbrot told Live Science's Our Amazing Planet. "Except for the fact that we cannot get these voltages to go away, I would call this 'crackpot physics,' and even as it is, I wish I could hedge my bets, but the voltages are very repeatable, and we have so far failed to account for a spurious influence that might cause them."

The effects are "so improbable that they could be wrong," Shinbrot said. "This is why we tested the effect in as different situations as possible." This included using a variety of particles, a variety of container materials and sizes, and a variety of humidity levels.

"Always we expect the effect will go away, and always it persists," Shinbrot said.

Unexplained electrical effects

The scientists previously sought to explain other mysteries regarding electrical charge. For example, it remains unclear how lightning can happen in sandstorms, even though sand is an electrical insulator, making lightning in sandstorms akin to seeing thunderbolts emerge from a storm full of rubber balls.

The researchers suggested there may be some unknown material property that produces voltages whenever cracks appear in powders or grains.

"There are analogous - and also largely unexplained - effects seen in other materials," Shinbrot said. "These go by the name of 'fractoluminescence,' and appear as flashes of light when wintergreen Life Savers [candies] are broken in a darkened room, when transparent tape is peeled from a roll or when mercury slips on glass."

Discovering the roots of this phenomenon could help scientists better predict earthquakes, Shinbrot said. Also, "Incipient cracks in ceramics could perhaps be detected in advance of failure," which could help authorities detect when bridges might collapse or ceramic turbine blades might shatter, he added.

The scientists will detail their findings March 6 at the annual American Physical Society's March meeting in Denver.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter