- Rocks make metallic and wooden sounds, in many different notes

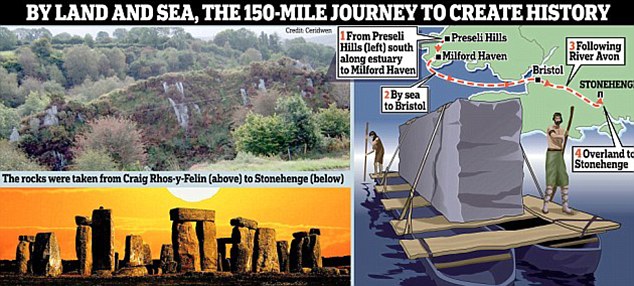

- Monoliths were moved by Stone Age man from Wales to Stonehenge

- Researchers believe their musical make-up could be why they were moved

Stonehenge may have been built by Stone Age man as a prehistoric centre for rock music, a new study has claimed.

According to experts from London's Royal College of Art, some of the stones sound like bells, drums, and gongs when they are 'played' - or hit with hammers.

Archaeologists, who have pondered why stone age man transported Bluestones 200 miles from Mynydd Y Preseli in Pembrokshire, South West Wales to Stonehenge, believe this discovery could hold the key.

The 'sonic rocks' could have been specifically picked because of their 'acoustic energy' which means they can make a variety of noises ranging from metallic to wooden sounding, in a number of notes.

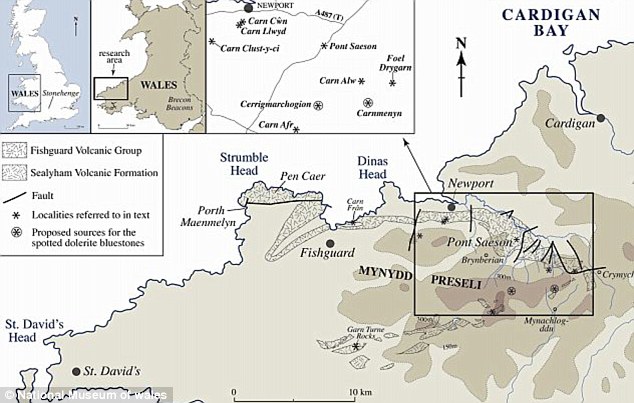

Research published today in the Journal of Time & Mind reveals the surprising new role for the Preseli Bluestones which make up the famous monument, and which were sourced from the Pembrokeshire landscape on and around the Carn Menyn ridge, on Mynydd Preseli, South-West Wales.

Bluestones were used in the village of Maenclochog - meaning bell or ringing stones - until the 18th century.

The Landscape & Perception project drew upon the comments of the early 'rock gong' pioneer, Bernard Fagg, a one-time curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum, in Oxford.

He suspected there were ringing rocks on or around Preseli and suggested that this was the reason why so many Neolithic monuments exist in the region - with the sounds making the landscape sacred to Stone Age people.

To the researchers' surprise, several were found to make distinctive if muted sounds, with several of the rocks showing evidence of having already been struck.

The stones make different pitched noises in different places and different stones make different noises - ranging from a metallic to a wooden sound.

The investigators believe that this could have been the prime reason behind the otherwise inexplicable transport of these stones nearly 200 miles from Preseli to Salisbury Plain.

There were plentiful local rocks from which Stonehenge could have been built, yet the bluestones were considered special.

The principal investigators for the Landscape & Perception project are Jon Wozencroft and Paul Devereux. Wozencroft is a senior lecturer at the RCA and the founding director of the musical publishing company, Touch.

Jon Wozencroft told MailOnline it was 'amazing' to find that the stones used in the monument make the noises that the researchers hoped for.

'It was a really magical discovery and refreshing to come across a phenomenon you can't explain,' he said.

The researchers have looked into geological reasons as to why some rocks make noise and others do not and one theory is that the amount of silica in the rocks could explain why in the future.

'Walking around Mynydd Y Preseli you can't tell which stones will make sounds by sight, but in time you get a sort of intuition by the way they are positioned,' he said.

The researchers had feared the musical magic of the stones at Stonehenge might have been damaged as some of them were set in concrete in the 1950s to try and preserve the monument and the embedding of the stones damages the reverberation.

Mr Wozencroft said 'you don't get the acoustic bounce' but when he struck the stones gently in the experiment, they did resonate, although some of the sonic potential has been suffocated.

In Wales, where the stones are not embedded or glued in place, he said noises made by the stones when struck can be heard half a mile away.

He theorised that stone age people living in Wales might have used the rocks to communicate with each other over long distances as there are marks on the stones where they have been struck an incredibly long time ago.

He believes that Stonehenge can be described as the first real musical instrument - after the voice and basic drums - and it had the potential to be make noise over long distances, a little like a chruch tower.

The researchers believe both Stonehenge and the site where the stones were from were venerated.

They think Stonehenge could have been used to make noises for special rituals.

'It could have been used for periodic special spiritual occasions - the sound is mysterious,' he said.

Devereux is a research associate of the RCA, editor of the academic journal, Time & Mind, and is currently working on a book, Drums of Stone, which will tell the full story of musical rocks in ancient and traditional cultures.

THE STONEHENGE EXPERIMENT

This experiment was the first time researchers have been able to strike - or tap - the monument to explore its sonic noise potential.

They used rounded hammers made from quartz hammerstone to strike the stones - although our ancestors might have used flint.

They tapped the stones 'very slightly' and could tell quickly if they would get a reverberation.

'Different sounds can be heard in different places on the same stones,' said the researchers.

The blue squares seen in the photos are used so that the special hammers do not leave a mark on the Bluestones.

Oh I get it.....it's a 'pun?

Interesting claim, I'm curious though, do the stones show signs of having been 'played'?