© Unknown

Bats are not normally considered essential parts of the ecosystem, but they are an integral part in balancing the natural infrastructure of the world, particularly in insect population control. Areas where the bats have been hit by WNS have noted a measurable increase in insects, including those that are damaging to crops.

Here's what we know. A white fungus grows on the face and wings of bats as they hibernate in lower temperatures. This stirs the bats and makes them active prematurely. As a result of increased activity during times of limited food supply, they die. Estimates are conservative placing the deaths of bats in North America at around 6 million since it was first noted in 2006.

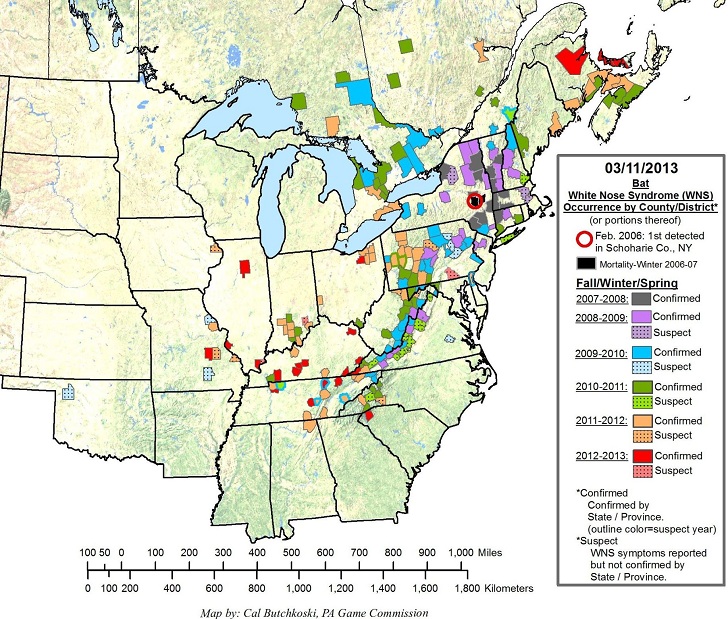

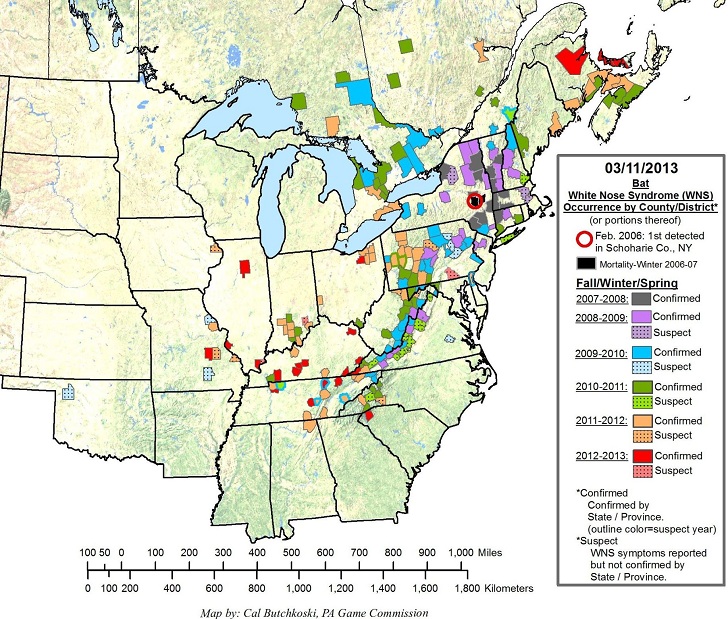

The spread is continuing. It starts in caves and spreads throughout them where tens of thousands of bats may be hibernating. It then spreads bat to bat, infecting other caves as a result. From Canada to Alabama and from the east coast to the Mississippi river,

more bat caves are

being infected every month.

There is a distinct potential for an ecological collapse that could affect other animals, plants, and even humans. Bats are the primary control animal that keep insect populations at a proper level. Reducing bats without a reduction in insects can cause a exponential increase in the population; fewer bats means more insects living longer to reproduce. It isn't just that fewer insects are being eaten. It's that more of them are then able to make even more. In other words, it's not a 1:1 ratio. The increasing imbalance of the insect population can have catastrophic effects on food supplies.

Today, it's present in

22 states and Canada.

"We have been expecting WNS in South Carolina," said Mary Bunch, wildlife biologist with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources. "We have watched the roll call of states and counties and Canadian provinces grow each year since the first bat deaths were noted in New York in 2007."

The scale and implications of this phenomenon are having an effect on those who understand them. Dr Scott McBurney of

Atlantic Veterinary College says this is the worst epidemic he's ever seen.

© Cal Butchkovski

"I'm saddened and I'm depressed, to be perfectly honest with you, because this is the most catastrophic wildlife disease that's affected a wildlife population, at least in my lifetime," McBurney said. "It's catastrophic because it's affecting so many species of bats, and because of the level of mortality associated with the infection, so it's just horrible."

Here is a map from the

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. If the spread continues and no solution is found, this could dramatically affect everyone in North America and as a result everywhere in the world.

I have seen (don't have link) that the fungus that causes "white nose" is the same fungus that forms the white covering to brie cheese. Also, that European bats are immune to this disease.

It would be ironic if something like this should affect, say, only the upper .5%. and they should come down with something similar.. like white butt syndrome or other such fatal disease:-)