© unknown

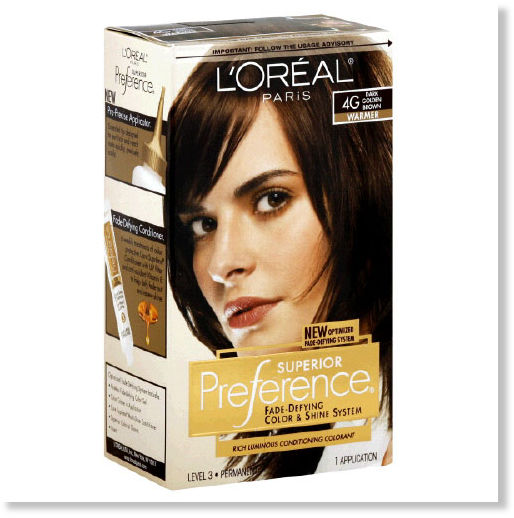

A 38-year-old woman from Keighley, West Yorkshire was in a coma last week following a suspected allergic reaction to a home hair dye. Doctors have given Julie McCabe, who coloured her hair with L'Oréal Preference colourant three weeks ago, an 8% chance of survival with little chance of a full recovery.

McCabe's case is the latest in a series of recent news reports linking the use of hair colourant to serious anaphylactic reactions. Anaphalactic reactions can be fatal. Less than a month ago, teenager Tabatha McCourt collapsed and died following what is believed to be an extreme reaction to a home hair dye kit she'd used just 20 minutes before.

The chemical culprit is widely believed to be p-Phenylenediamine (PPD), an organic compound used in over 99% of all permanent hair dyes, as well as in a variety of other applications, such as permanent makeup, black clothing and even newsprint (it is illegal in all other cosmetic products, so black eyeliners, mascaras and so on, are always PPD free). A known irritant, PPD allergies have the potential to affect 1.5% of the population.

In February, I was admitted to hospital after dying my hair. I had begun to feel unwell minutes after leaving the hairdresser and 10 minutes later was covered in large red welts, with very swollen limbs and extremities and a great deal of difficulty breathing. An ambulance was called and paramedics spent half an hour trying to stabilise me, while I suffered a serious fit. The hospital's doctors told me they had almost certainly saved my life. Everything pointed towards PPD as the likely aggressor. I have now stopped using permanent colourant. But in Britain alone hair dye is still used 100m times a year (60% of these in the home). So why is something as potentially dangerous as PPD still so ubiquitous?

© Ben Lack/Ben Lack Photography LtdJulie McCabe and Tabatha McCourt.

PPD is the

most effective known method of covering grey hair and, currently, there are no approved alternatives. Market leading brands such as Clairol, Avon and L'Oréal seem in no rush to find replacements to the ingredient while smaller companies don't have the necessary resources without their support. Some temporary colourants (lasting for six to eight washes and not covering grey) are PPD free, but virtually all semi-permanent and permanent colourants contain the ingredient. Even those without PPD are almost certain to contain "PTD", a compound so similar that those allergic to the former will almost always be allergic to that too (and which needs to be used in around double the quantities of PPD).

The Cosmetic, Toiletries and Perfumery Association (CTPA) claims that only a tiny percentage of the population has the potential to develop an allergy to PPD, but an article in the

British Medical Journal in 2007 called for more investigation into the safety of hair dyes after an increase in allergic reactions in recent years. The EU has recently reduced legal PPD levels (despite some recent newspaper reports to the contrary, no European countries have a PPD ban in place, nor does the US), to a maximum of 2% when the mixed dye is applied to the hair (in general, the darker the colour - in my case a deep brown, the more PPD a dye will contain).

Many women might assume that "natural", "organic" and "eco" hair dyes are PPD-free, but this is rarely the case. There is currently no hair colour on the market that covers all grey without PPD or PTD (henna, though PPD free, can't achieve the same effect). There is a glimmer of hope courtesy of companies such as OCS, who make ammonia-free hair dyes, which require lower levels of PPD (an average of around 0.4% rather than the more common 2%) to make them work, but some PPD remains, nonetheless.

The message from the hair companies is always to do an allergy test at least 48 hours before application, as specified on the packaging. This is sound, if unsatisfactory, advice. I went to a well-respected salon where a skin test was carried out well in advance and my highly qualified colourist did everything he should. Yet I still found myself, one hour later, in an ambulance with paramedics unsure if I'd even make it to the hospital. The CTPA admits that skin allergy tests are neither conclusive nor infallible.

I had been dyeing my hair for almost 20 years, with the same popular brand of colourant, and had never experienced anything more than mild itching and slight redness around the hairline. Yet one day, for no discernible reason, the same process very nearly killed me.

Reader Comments

("henna, though PPD free, can't achieve the same effect")

Not true. Henna mixed with a T spoon of apple cider vinegar and a T of lemon juice in a glass bowel and plastic spoon (no metal) not only covers grey, it last longer than any chemical coloring. It will cover the virtually white hairs around my face for months--until it grows out. It does not wear off or fade so make sure the color is one you like before you do your whole head.

While henna is a plant product and an allergy to a plant is a possibility, there is no comparison in risk and it thickens the hair and makes it glossy and healthy feeling.

Also, stop using all shampoo products with any version of sodium laural sulfate for even healthier hair and scalp--read the "No Poo" thread in the "Diet and Health" section of the SOTT Forum for more information.

After having bad reactions to salon dyes, including open sores on scalp, I decided to go to henna and it is amazing. If you get quality henna, and mix it with citrus (juice of lemon and grapefruit) it covers white and grey hair permanently. My salon applies it for me (it is messy) and then I do touch-ups on my roots and hairline for six months. The color on the rest of the hair does NOT fade at all during this time!