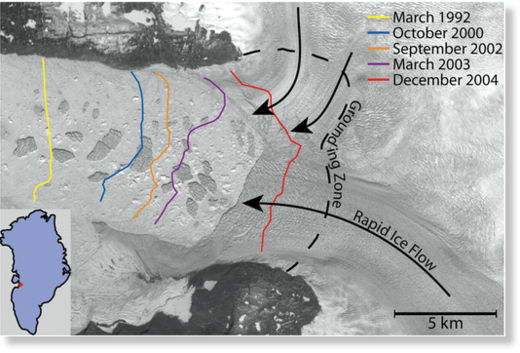

The finding, by University at Buffalo geologists working in Greenland, stems from new research on Jakobshavn Isbrae, a tongue of ice extending out to sea from Greenland's west coast.

Through an analysis of adjacent lake sediments and plant fossils, the UB team determined that the glacier, which retreated about 40 kilometres inland between 1850 and 2010, expanded outward at a similar pace about 200 years ago, during a time of cooler temperatures known as the Little Ice Age.

"We know that Jakobshavn Isbrae has retreated at this incredible rate in recent years, and our study suggests that it advanced that fast, also," said Jason Briner, the associate professor of geology who led the research.

"Our results support growing evidence that calving glaciers are particularly sensitive to climate change," Briner added.

Jakobshavn Isbrae has been the focus of intense scientific interest because it is one of the world's fastest-flowing glacier, releasing enormous quantities of Greenland's ice into the ocean.

Changes in the rate at which icebergs calve off from the glacier could influence global sea level rise.

An analysis of sediment layers from the bottom of Iceboom Lake showed that Jakobshavn Isbrae reached Iceboom lake about 20 or 25 years later, around 1820.

Jakobshavn Isbrae's rate of expansion from Glacial Lake Morten to Iceboom Lake, as documented by the UB team, matched the glacier's rate of retreat between those two points.

A paper detailing the results is in press and available online in Quaternary Science Reviews, a top peer-reviewed journal in the field.

Comment: Now, imagine a sudden drop in global temperatures, due to external and cosmic related influences, then consider the following excerpts from Superluminal Communications:

February 22, 1997: March 18, 2000: