|

| ©Unknown |

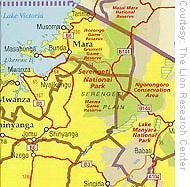

| Located in Northeastern Tanzania, the Serengeti National Park has the greatest concentration of large mammals in the world |

Wild lion populations can generally tolerate a certain level of parasites and disease. But new research shows that extreme climate conditions - such as severe droughts - can cause infection rates to skyrocket, resulting in mass die-offs. Véronique LaCapra reports.

The savannas of Tanzania are home to as many as half of the world's lions. University of Minnesota ecology professor Craig Packer has been studying lions in Tanzania's Serengeti National Park for the past 30 years. He was there in 1994, when inexplicably, the animals started dying.

He estimates that about 1,000 lions died over a relatively short period of time. Packer says it was unprecedented. "Over the previous 30 years nothing had been seen anything like it."

Then, in 2001, it happened again. "In the nearby Ngorogoro crater we saw another die-off," says Packer, "just like the one in the Serengeti seven years earlier."

|

| ©Unknown |

| About 3,000 lions (Panthera leo) inhabit the savannas of the Serengeti |

About 3,000 lions (Panthera leo) inhabit the savannas of the Serengeti.

By analyzing the lions' blood, Packer and his colleagues found that the two die-offs seemed to be triggered by outbreaks of canine distemper virus, a disease that usually affects domestic dogs.

Packer describes distemper as the "carnivore equivalent of measles." When a person gets measles, their body produces an immunological response to the virus, so that if the same person is infected again, the disease will not develop.

"Distemper has the same effect in the bodies of carnivores," Packer explains. "Whenever an animal is exposed to distemper, the animal - if it survives the infection - has antibodies and is therefore immune to further cases."

According to Packer, it's relatively common for lions to get the disease. In the Serengeti, he has seen distemper outbreaks about every six or seven years, usually with no symptoms. "Most of the time it's harmless, you just find out that the animals were exposed because you see their antibodies in their blood."

But in 1994 and 2001, about a third of the animals that got infected, died. What had turned a normally benign outbreak into a devastating epidemic?

The Serengeti National Park covers an area of about 15,000 square kilometers The Serengeti National Park covers an area of about 15,000 square kilometers Packer says that in 1993, in the Serengeti, "we had the first in a series of pretty serious droughts that we've been having out in East Africa."

The drought was especially brutal for a common prey of lions, the Cape buffalo. For the lions, the drought-weakened buffalo made an easy catch: they ate almost nothing else. But the unexpected feast came at a high price. "The buffalo," Packer explains, "were infested with ticks."

And with them, came a tick-borne parasite, called babesia. Animals in the Serengeti are always exposed to ticks and babesia, which at its worst can cause malaria-like symptoms, anemia, and hemorrhaging. In a normal year, Packer says, lions can tolerate the parasite. "But [...] the drought of 1993 led to an unprecedented increase in the lions' exposure to babesia."

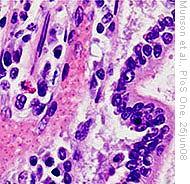

|

| ©Unknown |

| Magnified image of the capillaries of the small intestine of an adult lion that died during 2001 epidemic. The capillaries are blocked by red blood cells parasitized by Babesia |

And then, as soon as the drought ended, distemper struck the babesia-ridden lions. The combination proved fatal. As Packer puts it, "getting canine distemper is like having a short sharp bout of AIDS."

Like AIDS, the distemper virus attacks the immune system, weakening the body's defense against other infections. "So the virus kind of liberated the tick-borne disease so that it could be far more destructive than it would have otherwise been," explains Packer.

Although the lion populations were able to recover from the die-offs within a few years, Packer thinks deadly epidemics will become more frequent if climate change continues.

"What we're seeing now is much greater variability in the weather than we'd ever seen in the past." Packer says that most climate change models predict a greater variance in weather, with a greater chance of flood or drought in any given year. "That's definitely been the experience in my 36 years in working out here."

Packer adds that extreme droughts and floods are likely to continue unleashing new, potentially synergistic combinations of diseases, which could be more deadly together than they would be on their own. His research is published in the journal PLoS ONE.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter