Standing in a lava field about three kilometres from the mountainside, I watched boulders the size of Chevy Suburbans fly out of the clouds and tumble down the grey and black slope.

|

| ©Rural Costa Rica |

| The Arenal Volcano during a sunset. |

Oddly, the volcano's audience treated the spectacle with casual curiosity. A dozen Dutch and German tourists sat or leaned on black pumice boulders, chatting while they scoped the geological show with their binoculars.

"Doesn't this make you a little nervous?" I asked my guide, Alexander Araya.

"A little. See that lake?" he pointed to a body of water a couple of kilometres behind us. "The old town of Arenal is under there. It was destroyed when the volcano blew up in 1968. This thing has been active every day since. It can throw a boulder five or six kilometres."

During a four-day excursion across Costa Rica's interior, I often had the feeling that I was watching a special-effects-laden movie instead of experiencing reality. Maybe it was suddenly going from the grey world of a Midwest winter to the saturated colours of the equatorial tropics, but everything -- the exploding volcano, the cloud forest as viewed while flying down a steel cable, a flock of iridescent hummingbirds -- seemed too extravagant to be true.

Araya, 31, added to the sense of disassociation. Perpetually clad in wraparound shades, he told outrageous stories with disarming nonchalance and an utter lack of irony. When we checked into a hotel near the volcano, he told me not to get too close to bushes or trees with my camera because of the abundance of poisonous snakes.

"The fer-de-lance is the only aggressive one. If he sees you coming, he'll come out toward you," Araya said. "My uncle got bit by one. Blood comes out your eyes and pores. He was in the hospital six months, but don't worry, he survived it."

At the juncture between North and South America and between the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea, Costa Rica compresses an intense amount of geography and wildlife into a very small country about 500 km north of the equator.

The character of the people who live amid all these phenomena is interestingly relaxed. They are known to other Latinos (and to themselves) as Ticos, for the Costa Rican tendency to add the Spanish diminutive to nearly every noun. In Costa Rica, a coffee is un cafecito.

With milk? Con lechita.

That tendency seems representative of an affectionate and non-violent outlook on life. Araya proudly told me that the country hasn't had a standing army since 1948, and that the money is better spent on schools. "Tourism is the No. 1 industry," Araya said, "but high-tech is No. 2. And that's because everyone here can get an education."

The people are non-violent, but the landscape isn't. There are more than 100 volcanoes in Costa Rica and at least five are active. Arenal, reliably rumbly, has become a hub of geo- and eco-tourism. The volcano provides heat for a number of hot-spring spas, and a dramatic setting for a number of other attractions, such as a private park with hanging bridges suspended in the rain-forest canopy.

We spent the morning hiking in

Arenal National Park, a rain-forest preserve at the base of the volcano. There, stark evidence of the Earth's potential for destruction was brightened by its powers of creation; orchids sprouted from crevices in lava, from trees, from the damp forest floor. An orchestra of insects, frogs and birds made the air vibrate. Down the trail, Araya pointed out a termite mound, as big as a cluster of bowling balls, growing around a tree stump. The tiny bugs crawled around the nest.

"These are the kind that are good to eat," he said with a nostalgic sigh. "I used to eat a lot of them when I was a kid -- like candy. Now, I just can't do it. They work so hard to build that nest. I feel guilty to break it up."

That Araya would feel guilty about breaking up termite nests to eat the bugs seemed to fit the stereotype of the peaceful Costa Rican. I had a harder time putting the zip-line phenomenon into any kind of context.

A day after leaving the volcano, I joined several other tourists in climbing a tall scaffolding, attaching myself to a pulley on a high-tension steel cable and then taking off on a high-speed journey through the upper canopy of the cloud forest. It was another surreal experience, kind of like being Tarzan, if Tarzan wore a hockey helmet and a neon-orange jumpsuit.

Light rain added luster to every leaf in the jungle on the morning I showed up at Selvatura Canopy Tours in the mountain town of Monteverde.

I went through a 10-minute orientation with a honeymooning couple from Toronto. Briefly, we were taught how to brake with our heavy leather gloves and how to keep our feet forward (in case the braking doesn't work, you don't want to come to a stop against a tree with your head -- it makes sense).

The "tour" consisted of sliding down nine cables strung down the side of a cloud forest mountain. The longest, we were told, was 600 metres. We had a minder in front of us (to help us make safe landings) and one behind (to push us along if we got stuck in the middle of a cable; it is possible to brake too much.)

The climax of the trip was the "Tarzan swing," a 16-metre cable strung from the branch of a massive tree. The Canadian groom and I climbed an 18-metre high platform. I went first. There was quite a bit of falling straight down before the cable caught and I became a 90-kilogram pendulum. I was told that I let out a strangled scream as I dropped. When the Canadian's turn came, his legs shook like Bugs Bunny's about to get shot by Elmer Fudd.

I was happy to have my feet back on the ground the next day, when Araya and I spent several hours hiking in Monte Verde's main attraction: the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve.

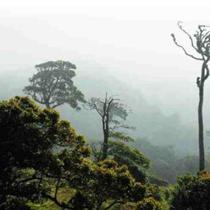

|

| ©Minneapolis Star Tribune |

| A magical view of the cloud forest reserve near Monte Verde, Costa Rica. |

At 1,200 to 1,500 metres high and straddling the country's continental divide, the reserve shelters more than 3,000 kinds of plants, 500 bird species and 120 mammals. For birders, the ultimate aim is to spot the rare resplendent quetzal, a spectrum-defying bird with a metre-long train of luminous feathers that might make a peacock jealous.

We hiked for hours. At times, the trail disappeared in thick fog. The moss-covered trees dripped. When the clouds parted momentarily, I could see we were walking along a ridge, with deep valleys on either side of the path. Every available surface supported life. In the cups of pineapple-topped bromeliads, poison-dart frogs sang. Along the trail, leaf-cutter ants busily carried their harvest to the colony. Araya shined his flashlight in a hole to illuminate a tarantula, as broad as my palm, lying in wait for its next meal.

Periodically, Araya blew a short double whistle, hoping to hear the wikka-wikka call of the quetzal in response. "When people see it, they cry," he said. "I've cried when I've seen one. There is something about them, a special energy. When one flies by, it's like the colours stay in the air behind it. I can see why the Maya thought it was a god."

|

| ©Traveling Costa Rica |

| A male Resplendant Quetzal |

Finally, a bird returned Araya's call. He set up his spotting scope and in short order identified a female, not quite as resplendent as her male counterpart, sitting quietly in a tree about 45 metres from the trail.

Through the scope, I saw a bird about the size of a crow, but radiating colours -- iridescent green and gold across the back, a glimmer of red near the tail, and checkered black and white tail-feathers. It was like a fragment of rainbow, living and breathing. A minute later, the quetzal flew away, vanishing into the clouds.

"You know, once I did the zip line a few times, I don't need to do it again," Araya said. "But I never get tired of this."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter