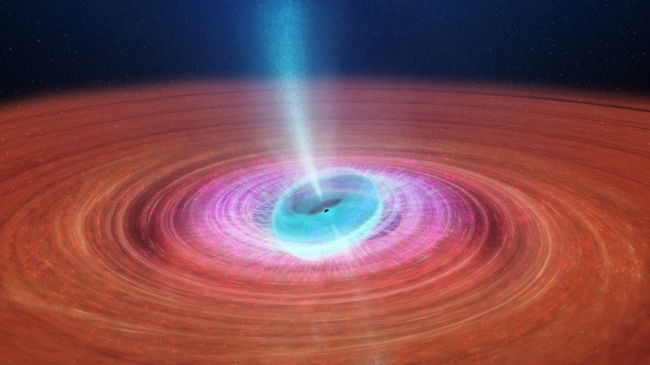

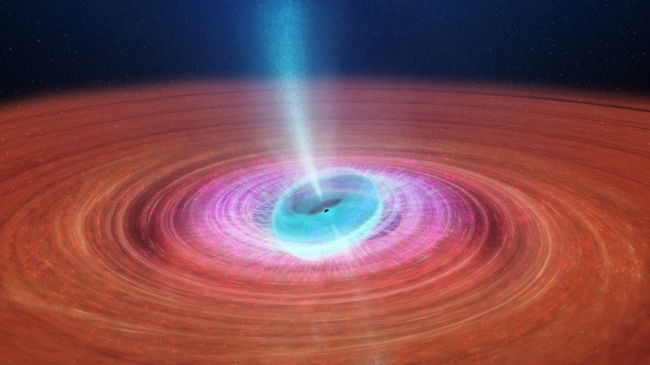

© ICRARAn artist's impression of the inner parts of the accretion disk around the black hole V404 Cygni.

Astronomers have spotted wildly wobbling jets of particles spewing out of a

black hole, and they think this unusually rapid motion could be happening because the black hole's strong gravity is warping space around it.

The black hole, named V404 Cygni, is located about 8,000 light-years from Earth and is

relatively small as far as black holes go - only nine times the mass of Earth's sun. It is part of a binary system in which it and a sun-like star orbit one another. The black hole is constantly siphoning material from its stellar companion, and as that material gets sucked in, it forms an

accretion disk around the black hole.

Some of the particles falling into the black hole

escape through relativistic jets, long beams of energetic plasma that flow from the black hole's axis of rotation at more than half the speed of light. Astronomers have

seen black hole jets before but

have never seen jets that wobble as rapidly as those from V404 Cygni, which were observed oscillating over time periods of only a few minutes.

Comment: There are some fascinating and fruitful discoveries here, although they also show how science can be so easily blinded by its own suppositions these days.

See also:

- Planet-X, Comets and Earth Changes by J.M. McCanney

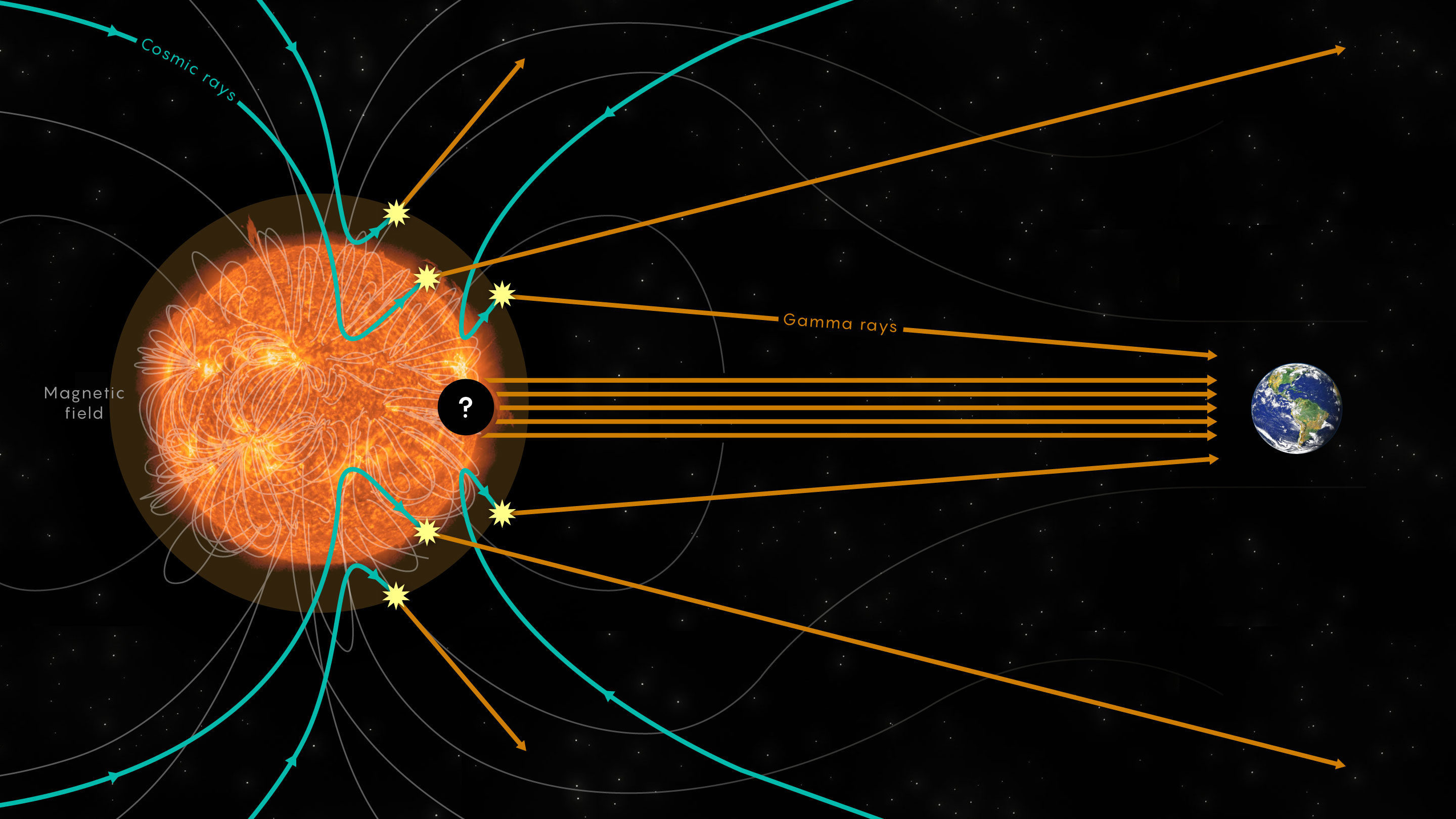

- The sun's magnetic field is ten times stronger than previously believed

- NASA footage captures sun shooting giant strands of plasma (VIDEO)

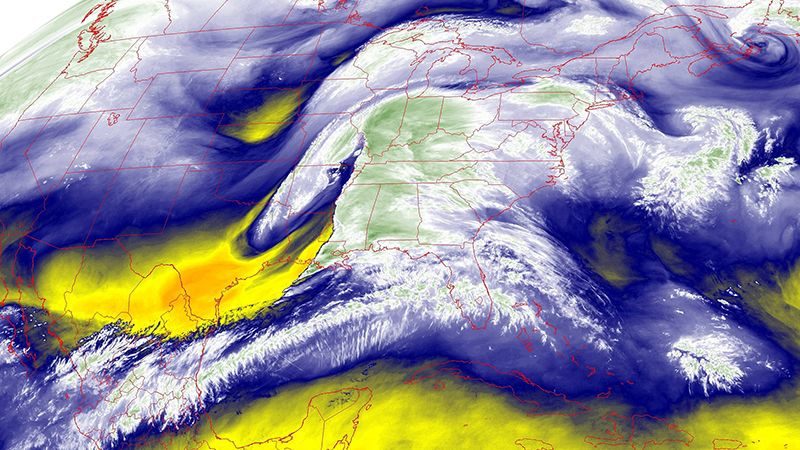

- Electric Universe: Supersonic plasma jets discovered in Earth's atmosphere

Also check out SOTT radio's: