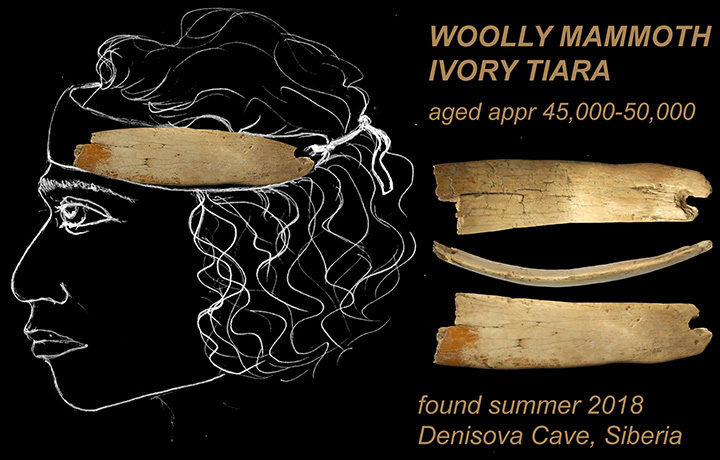

The suspicion is that the tiara - or diadem - was made by Denisovans who are already known to have had the technology 50,000 or so years ago to make elegant needles out of ivory and a sophisticated and beautiful stone bracelet.

The tiara maybe the oldest of its type in the world.

It appears to have had a practical use: to keep hair out of the eyes; it's size indicates it was for male, not female, use.

Another theory, although related to tiaras made 20,000 years later by people living around river Yana in Yakutia is that they could have denoted the family or tribe of ancient man, acting like a passport or identity card.

There were, though, no religious symbols or ornaments on the woolly mammoth tiara - made at a time when the giant species still roamed Siberia with ancient man as a predator.

The Palaeolithic tiara can be dated to between 45,000 to 50,000 years, and was worn by a man with a large head, according to researcher Alexander Fedorchenko, from Novosibirsk Institute of Archeology and Ethnography.

There is a hole in the rounded end of the tiara, where a cord was threaded to tie the it at the back of the head.

Earlier a small piece of a frontal part of an ornamented mammoth ivory tiara was found in the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia.

The latest discovery adds to the theory of Siberian researchers that the ancient inhabitants of the cave wore tiaras for many millennia and most likely produced them.

The fact of manufacturing is evidenced by numerous fragments of mammoth tusk found inside the cave.

'Finding one of the most ancient tiaras is very rare not just for the Denisova cave, but for the world. Ancient people used mammoth ivory to make beads, bracelets and pendants, as well as needles and arrow heads', said Fedorchenko.

'The fragment we discovered is quite big, and judging by how thick the (strip) is, and by its large diameter, the headband was made for a big-headed man.'

He explained that some 50,000 years after it was made, it fitted his own temple and the back of his head.

Its diameter could have changed with years due to gradual straightening of the curved part, he said.

'Mammoth ivory plates were first thoroughly soaked in water to become more ductile and not crack during processing, and then they were bent under a right angle,' he said.

'Any bent object tends to return to their original shape over time.

'This is the so-called memory of the shape effect. We must remember this while trying to judge the size of the head of the tiara's owner by its diameter.'

The world famous Denisova cave first caught the attention of Soviet scientists in 1970s, when they found palaeo-archeological remains which led to further research.

Now the site on the border of Altai region and the Altai Republic, in the south of western Siberia, has a permanent research camp, seen as the pride of Novosibirsk Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography.

'We have quite a collection of mammoth ivory found inside the Denisova cave, thirty pieces in total with various types beads, three rings, parts of bracelets and arrowheads', said Fedorchenko.

'Finding a piece as big as tiara is an incredibly rare discovery for Siberia.

'There were mammoth ivory tiaras, including some decorated, found on Palaeolithic sites in the extreme North and in the east of Siberia.

'But these tiaras were created much later, from 20,000 to 28,000 years ago.'

Such examples are from the Yana site in Yakutia.

The tiara is a gift for trace evidence experts as it shows all possible ways of processing mammoth ivory used by ancient men from the Denisova Cave, like whittling, soaking in water, bending, grinding, polishing and drilling.

'These are all possible technologies from A to Z typically used in the Paleolithic time, but which are usually associated with activities of Homo sapiens.

'Here we likely deal with another, more ancient culture, because there was not a single piece of bone belonging to a Homo sapiens found in the cave', said Fedorchenko.

Comment: And yet homo sapiens were in the area at the time: Siberia: 50,000 year old bones may be the oldest Homo sapiens outside Africa and Middle East

What the Siberian scientist did find were bones of a new type of human that was named Homo altaiensis, or Denisovan.

The researchers are still working with the precious piece of mammoth ivory, defining its dating and reconstructing the tiara.

Once assembled, there will be pictures and drawings of what the tiara looked like many millennia ago.

There is a good chance other pieces of the tiara will be found.

'The mammoth ivory is so durable it keeps for centuries. As long as other pieces of tiara were not damaged or eaten by cave hyenas, we will find them,' said Fedorchenko.

He explained the issues researchers face when dating pieces made of mammoth ivory.

The radiocarbon method gives the date of the mammoth's death, but the age of the tusk and the time it was processed might differ for dozen thousand years.

To get a more accurate dating, scientists have to date the archeological layer where the tiara was found.

This can be done by radiocarbon dating of animal remains found in this layer, or by using a more up-to-date Optical Dating method.

This technology allows experts to establish the time when the culture-containing layer was upper and revived daylight (photons).

A finger bone fragment of 'X woman', a juvenile female, found in Denisova cave in 2008. Picture: Max Planck Institut

Earlier this year details were revealed in Nature journal of the discovery of evidence of an inter-species child called Denny who lived some 90,000 years ago.

She was the product of a sexual liaison between a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father, according to DNA findings.

Other discoveries in the cave include bracelet made from made from stunning green-hued chlorite, bead jewellery from ostrich eggs, and a needle - still useable today.

These testify to their talents, say archeologists.

Denisovan blood lives on, but nowhere near Siberia.

Remarkably, Denny's relatives - with five per cent Denisovan DNA - are the native peoples of Australia and Papua New Guinea, presumably after her descendants gradually migrated eastwards from Siberia - interbreeding as they journeyed.

Comment: Extinct Denisovan people may have colonized Earth's highest plateau in Tibet 30,000 years ago

The Denisovans were first identified a decade ago when a tiny finger bone fragment of so-called 'X woman' was discovered, a young female who lived around 41,000 years ago.

She was found to be neither Homo sapiens nor Neanderthal.

Comment: The exact function of the diadem and the details of its owner remains to be seen, but what is fascinating is the length of time these were being manufactured and the other insights its presence shines on the lives of the Denisovans.

See also: