Researchers said on Tuesday they had found its first known victim: a hunter-gatherer who lived 5,000 years ago in what is now Latvia, whose remains carried the Yersinia pestis bacteria that causes the disease.

"The analyses of the strain we identified shows that Y. pestis evolved earlier than thought," Ben Krause-Kyora, head of the aDNA Laboratory at the University of Kiel in Germany, said.

Krause-Kyora and colleagues wrote in a paper in the journal Cell Reports the bacterial lineage emerged as far back as 7,000 years ago when it split from its predecessor, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis.

The new date pushes the previously held timeline back by 2,000 years.

Comment: Interestingly, an unknown strain of Yersinia pestis was detected in a 5000 year old tomb of a 20 year old female farmer in Sweden.

The bacteria was missing key genes, such as one that enabled it to be spread via fleas - meaning the ancient strain was both less contagious and deadly than the medieval version.

Comment: Research shows that the plague as we know it is not spread by fleas: Book Review: New Light on the Black Death by Mike Baillie

Scott and Duncan explain how Yersinia pestis has never persisted in any European rodents because they are not resistant. In addition to that, the only species of rats in Europe came either some 60 years after the last European plague or could not survive without a warm climate, making it impossible to spread infection rapidly and wildly in winter.

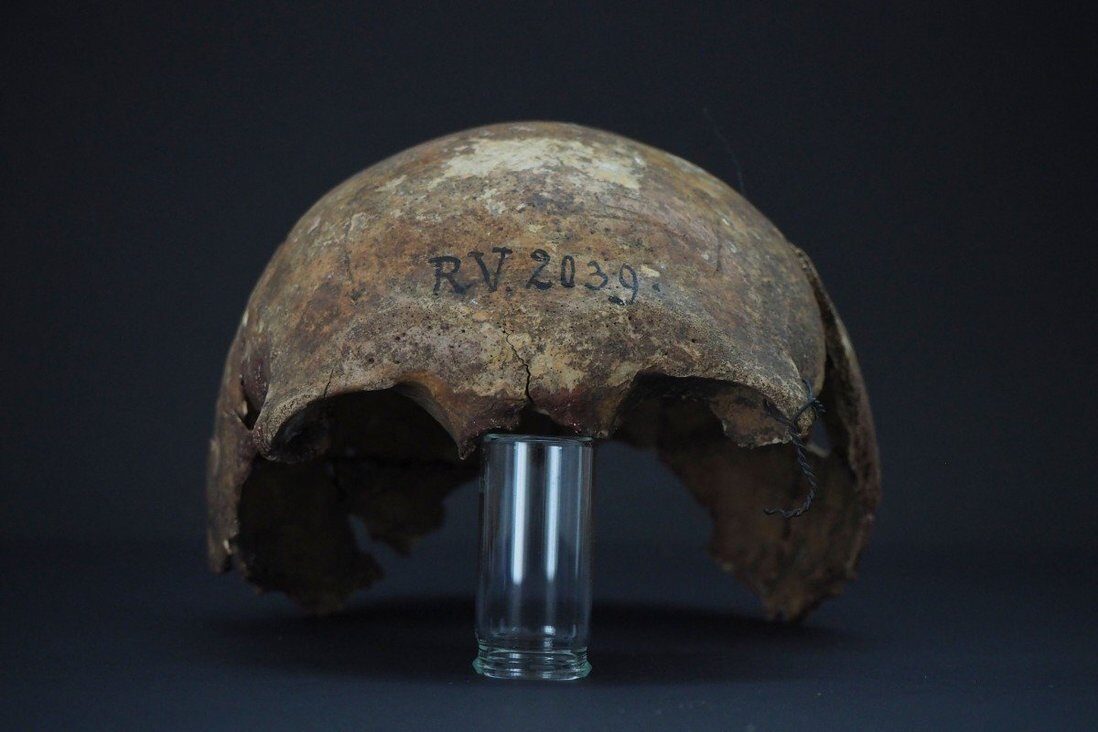

The hunter-gatherer was a man in his twenties called "RV 2039". He was one of two people whose skeletons were excavated in the late 19th century from a region called Rinnukalns in present-day Latvia.

The remains vanished until 2011 when they reappeared as part of the famed German anthropologist Rudolph Virchow's collection.

Following this rediscovery, two more burials were uncovered from the same site.

The plague finding "was really a surprise", said Krause-Kyora: the team was sequencing the teeth and bones of the four individuals to determine if they related to each other when they stumbled on the discovery.

Evidence of Y pestis was found in RV 2039's bloodstream, and it probably killed him, though researchers think the disease course might have been slow.

He had a high level of bacteria in his blood at the time of death, and that has been linked to less aggressive infections in rodent studies.

The people around him were not infected, and he was buried carefully, meaning he was unlikely to have had a highly contagious respiratory version called pneumonic plague.

Researchers think instead he was infected by a single direct contact, such as a rodent bite, in keeping with other Neolithic findings.

"We see it in societies that are herders in the steppe, hunter-gatherers who are fishing, and in farmer communities - totally different social settings but always spontaneous occurrence of Y. pestis cases," added Krause-Kyora.

The growing population density probably triggered further adaptation of the bacteria.

Tracking the history of Y. pestis could also shed light on the ways in which human genomes evolved to keep up.

For example, around the same time as cities were forming in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, changes began to emerge in a set of human genes responsible for helping the immune system keep track of foreign pathogens.

"Therefore, we are very interested in future research into how these early infectious diseases influenced our present-day immune systems," said Krause-Kyora.

Comment: See also:

- New Light on the Black Death: The Viral and Cosmic Connection

- The Seven Destructive Earth Passes of Comet Venus

- Medieval plague outbreaks picked up speed over 300 years

- Did unknown strain of plague discovered in 5000 year old tomb wipe out Europe's stone age civilization?

And check out SOTT radio's: Behind the Headlines: Who was Jesus? Examining the evidence that Christ may in fact have been Caesar!