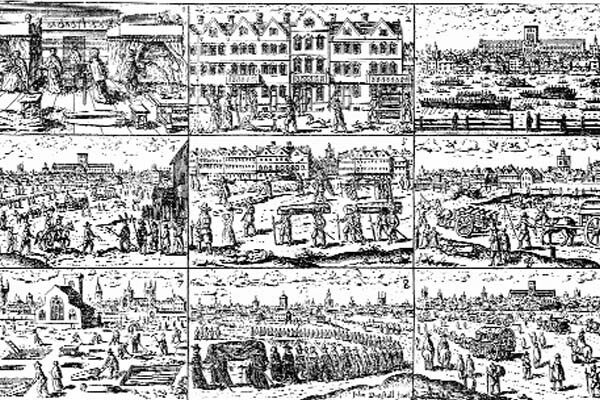

© National ArchivesThe Great Plague of 1665

McMaster University researchers who analyzed thousands of documents covering a 300-year span of plague outbreaks in London, England, have estimated that the disease spread four times faster in the 17th century than it had in the 14th century.

The findings, published today in the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

show a striking acceleration in plague transmission between the Black Death of 1348, estimated to have wiped out more than one-third of the population of Europe, and later epidemics, which culminated in the Great Plague of 1665. Researchers found that in the 14th century, the number of people infected during an outbreak doubled approximately every 43 days. By the 17th century, the number was doubling every 11 days.

"It is an astounding difference in how fast plague epidemics grew," says David Earn, a professor in the Department of Mathematics & Statistics at McMaster and investigator with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, who is lead author on the study.

Earn and a team including statisticians, biologists and evolutionary geneticists

estimated death rates by analyzing historical, demographic and epidemiological data from three sources: personal wills and testaments, parish registers, and the London Bills of Mortality.

It was not simply a matter of counting up the dead, since no published records of deaths are available for London prior to 1538. Instead, the researchers mined information from individual wills and testaments to establish how the plague was spreading through the population.

"At that time, people typically wrote wills because they were dying or they feared they might die imminently, so we hypothesized that the dates of wills would be a good proxy for the spread of fear, and of death itself. For the 17th century, when both wills and mortality were recorded, we compared what we can infer from each source, and we found the same growth rates," says Earn. "No one living in London in the 14th or 17th century could have imagined how these records might be used hundreds of years later to understand the spread of disease."

While previous genetic studies have identified Yersinia pestis as the pathogen that causes plague,

little is known about how the disease was transmitted.

"From genetic evidence, we have good reason to believe that the strains of bacterium responsible for plague changed very little over this time period, so this is a fascinating result," says Hendrik Poinar, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at McMaster, who is also affiliated with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research, and is a co-author on the study.

The estimated speed of these epidemics, along with other information about the biology of plague,

suggest that during these centuries the plague bacterium did not spread primarily through human-to-human contact, known as pneumonic transmission. Growth rates for both the early and late epidemics are more consistent with bubonic plague, which is transmitted by the bites of infected fleas.

Researchers believe that

population density, living conditions and cooler temperatures could potentially explain the acceleration, and that the transmission patterns of historical plague epidemics offer lessons for understanding COVID-19 and other modern pandemics.

This new digitized archive developed by Earn's group provides a way to analyze epidemiological patterns from the past and has the potential to lead to new discoveries about how infectious diseases, and the factors that drive their spread, have changed through time.

Fear works contagion, and biological responses perceived as retribution, cures or punishment can increase the fear and empower it to mistreat or abandon the living need in ways that compound the detoxification sickness and the narratives of identifying in fear.

The constraints of our current era do not readily allow a clear view of the past. We also live 'in' or through fear defined psychic-emotional systems.

Heads up for SOTT - Look up the Xhosa cattle killings.

There was a lockdownsceptic reference to it a couple of days ago

[Link]

About 2/3 down the page under a red image.

The Xhosa Cattle Killings

In the early nineteenth century, the British colonized Southeast Africa. The native Xhosa resisted, but suffered repeated and humiliating defeats at the hands of British military forces. The Xhosa lost their independence and their native land became an English colony. The British adopted a policy of westernising the Xhosa. They were to be converted to Christianity, and their native culture and religion was to be wiped out. Under the stress of being confronted by a superior and irresistible technology, the Xhosa developed feelings of inadequacy and inferiority. In this climate, a prophet appeared.

In April of 1856, a fifteen-year-old girl named Nongqawuse heard a voice telling her that the Xhosa must kill all their cattle, stop cultivating their fields, and destroy their stores of grain and food. The voice insisted that the Xhosa must also get rid of their hoes, cooking pots, and every utensil necessary for the maintenance of life. Once these things were accomplished, a new day would magically dawn. Everything necessary for life would spring spontaneously from the earth. The dead would be resurrected. The blind would see and the old would have their youth restored. New food and livestock would appear in abundance, spontaneously sprouting from the earth. The British would be swept into the sea, and the Xhosa would be restored to their former glory. What was promised was nothing less than the establishment of paradise on earth.

Nongqawuse told this story to her guardian and uncle, Mhlakaza. At first, the uncle was sceptical. But he became a believer after accompanying his niece to the spot where she heard the voices. Although Mhlakaza heard nothing, he became convinced that Nongqawuse was hearing the voice of her dead father, and that the instructions must be obeyed. Mhlakaza became the chief prophet and leader of the cattle-killing movement.

News of the prophecy spread rapidly, and within a few weeks the Xhosa king, Sarhili, became a convert. He ordered the Xhosa to slaughter their cattle and, in a symbolic act, killed his favourite ox. As the hysteria widened, other Xhosa began to have visions. Some saw shadows of the resurrected dead arising from the sea, standing in rushes on the river bank, or even floating in the air. Everywhere that people looked, they found evidence to support what they desperately wanted to be true.

The believers began their work in earnest. Vast amounts of grain were taken out of storage and scattered on the ground to rot. Cattle were killed so quickly and on such an immense scale that vultures could not entirely devour the rotting flesh. The ultimate number of cattle that the Xhosa slaughtered was 400,000. After killing their livestock, the Xhosa built new, larger kraals to hold the marvellous new beasts that they anticipated would rise out of the earth. The impetus of the movement became irresistible.

The resurrection of the dead was predicted to occur on the full moon of June, 1856. Nothing happened. The chief prophet of the cattle-killing movement, Mhlakaza, moved the date to the full moon of August. But again the prophecy was not fulfilled.

The cattle-killing movement now began to enter a final, deadly phase, which its own internal logic dictated as inevitable. The failure of the prophecies was blamed on the fact that the cattle-killing had not been completed. Most believers had retained a few cattle, chiefly consisting of milk cows that provided an immediate and continuous food supply. Worse yet, there was a minority community of sceptical non-believers who refused to kill their livestock.

The fall planting season came and went. Believers threw their spades into the rivers and did not sow a single seed in the ground. By December of 1856, the Xhosa began to feel the pangs of hunger. They scoured the fields and woods for berries and roots, and attempted to eat bark stripped from trees. Mhlakaza set a new date of December 11 for the fulfilment of the prophecy. When the anticipated event did not occur, unbelievers were blamed.

The resurrection was rescheduled yet again for February 16, 1857, but the believers were again disappointed. Even this late, the average believer still had three or four head of livestock alive. The repeated failure of the prophecies could only mean that the Xhosa had failed to fulfil the necessary requirement of killing every last head of cattle. Now, they finally began to complete the killing process. Not only cattle were slaughtered, but also chickens and goats. Any viable means of sustenance had to be destroyed. Any cattle that might have escaped earlier killing were now slaughtered for food.

Serious famine began in late spring of 1857. All the food was gone. The starving population broke into stables and ate horse food. They gathered bones that had lay bleaching in the sun for years and tried to make soup. They ate grass. Maddened by hunger, some resorted to cannibalism. Weakened by starvation, family members often had to lay and watch dogs devour the corpses of their spouses and children. Those who did not die directly from hunger fell prey to disease. To the end, true believers never renounced their faith. They simply starved to death, blaming the failure of the prophecy on the doubts of non-believers.

By the end of 1858, the Xhosa population had dropped from 105,000 to 26,000. Forty to fifty-thousand people starved to death, and the rest migrated. With Xhosa civilization destroyed, the land was cleared for white settlement. The British found that those Xhosa who survived proved to be docile and useful servants. What the British Empire had been unable to accomplish in more than fifty years of aggressive colonialism, the Xhosa did to themselves in less than two years.

Original by David Deming, Associate Professor of Arts and Sciences at University of Oklahoma. Copyright © 2009 by LewRockwell.com. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is gladly granted, provided full credit is given.