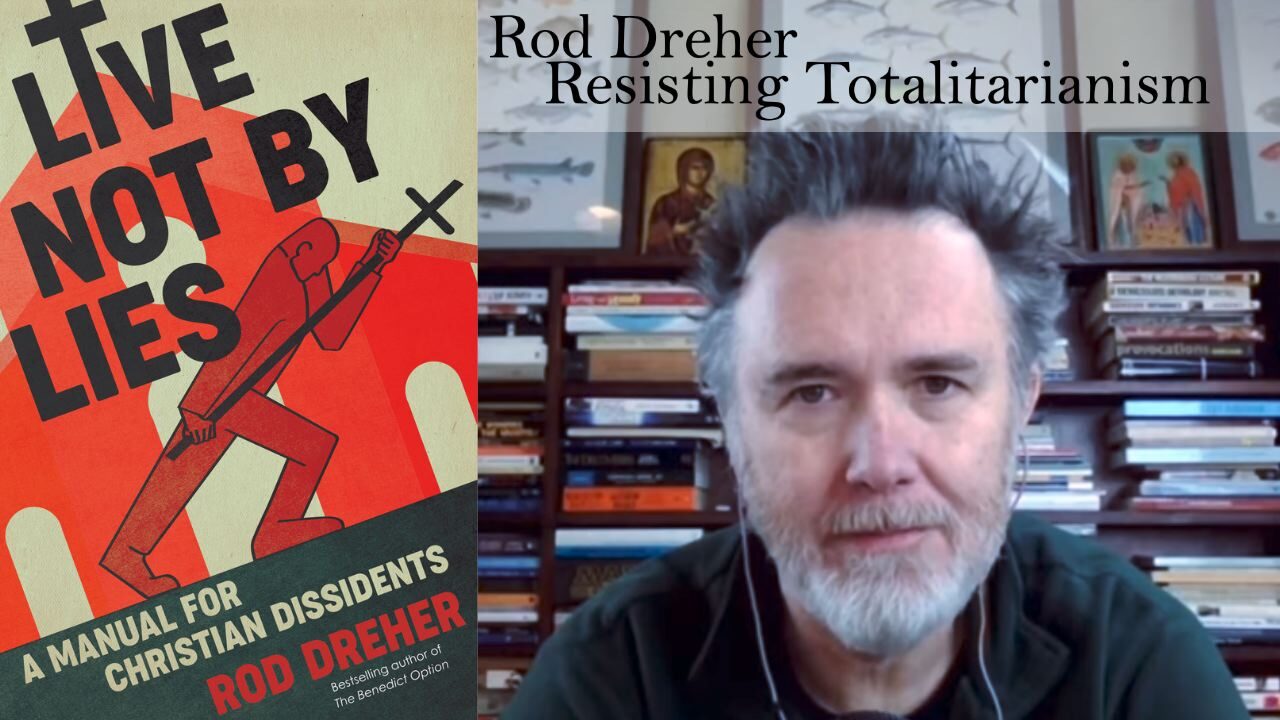

This week on MindMatters we discuss Live Not by Lies with Rod Dreher and take a hard look at the radical left's 'soft totalitarianism' already tearing away at the very fabric of society. Between Big Tech's cancelling of conservative perspectives, ideologically motivated political policies, mass consumer surveillance, and the misled foot soldiers that threaten to attack and burn all those who disagree with them, Dreher asks the prescient question - what should one do in the face of such an onslaught?

Making use of invaluable interviews and accounts of Christian dissidents who lived under communism in Eastern Europe, Dreher relates the thoughts, strategies and faith that assisted those who sought to live in truth under the harshest and most harrowing of communist regimes. We also delve into why the church and Christianity was specifically targeted and sought out as an enemy of the state, and why the conscience inherent in religion is quite often exactly what makes it such a powerful enemy of totalitarian thinking.

Running Time: 01:20:17

Download: MP3 — 73.5 MB

Here's the transcript:

Harrison: Today we have Rod Dreher. First Rod, did I pronounce your name correctly?

Rod: It's close enough.

Harrison: Close enough. How do you say it?

Rod: Dreer (phonetic) is actually how it's pronounced in German but here in south Louisiana we say Drayer (phonetic).

Harrison: Okay. Rod is a senior editor at The American Conservative and the author of this new book Live Not By Lies-A Manual for Christian Dissidents. We're going to be talking about this book today. It just came out last month Rod?

Rod: September 29th.

Harrison: September 29th, so a bit longer than that. Maybe to start out, could you give us an overview of what the book is and what inspired you to write it.

Rod: Sure. Well five years ago I got a phone call from a doctor in Minnesota. He was at the Mayo Clinic. A friend of mine was his patient and the man was really agitated and anxious. He said, "Look, I have to tell somebody this and it's going to be you." He said that his elderly mother was with him and his wife and that she is an immigrant from Czechoslovakia and she spent four years in prison in the 1950s in Czechoslovakia for practicing her catholic faith. He told me that mother told him that, "Son, the things I'm seeing happen in America now remind me of what it was like when communism first came to my country."

That just struck me as so weird and alarmist. So I made a point though, when I would travel around the US to conferences or to give speeches, if I would run into somebody who grew up either in the Soviet Union or in Soviet dominated Eastern Europe, I would put the same question to them, "Are you seeing things in America today that remind you of communism?" Every single one of them said yes. If you talked to them long enough they would be emphatic about how angry they were that Americans wouldn't take them seriously. The main thing they were talking about was 'cancel culture', the fear that they're going to come for your job because you said the wrong thing or believed the wrong thing, that sort of thing. That's how it starts but they say it inevitably gets worse and worse.

So that was the genesis of the book. What I've done in this book, in the first half of the book I try to explain what they're talking about, why are the things that are happening here in our liberal, capitalist democracy, why does it remind them of totalitarianism. Is our definition of totalitarianism too rigid? In fact I argue - we can get into this in our talk today - that it is too rigid, that what they're seeing is a soft totalitarianism but a totalitarianism nonetheless.

The second half of the book is based on my interviews and travels in Russia and Eastern Europe talking to Christians who were dissidents under the communist rule to find out what their experiences were like and what people - not just Christians but all people here in the United States and in the west more broadly - can learn from their experience about how we can live through a form of totalitarianism without losing our integrity. Also I not only talk to them but I've read through some of the literature of the dissident experience, Solzhenitsyn, Havel and others to try to glean practical lessons for American people in our own situation and also to give people some hope.

Harrison: I think that's a good thing and it comes through in the book, this element of hope, but I noticed there's also a kind of - I don't know if I would call it cynicism but almost a resignation. Maybe you can correct me if I'm wrong, if I'm not interpreting you correctly, but that it's already too late in a certain sense. Would you agree with that?

Rod: That's fair. I don't want to be defeatist about it but the things that I identify and the people I interviewed identify as markers of soft totalitarianism have gone very far. There just seems to be so little resistance to it because so many people don't even realize it's happening. And if they do think it's happening they believe their resistance is simply to vote republican as if that were going to be sufficient.

Now I'm politically involved but I think that to think that politics alone are going to solve this problem and meet this challenge is incredibly naïve. We're still not even talking about effective politics which, by the way, would be a politics that should unite people on the left and the right who believe in old fashioned liberal values. But we're not there. We're not even talking about this yet.

Harrison: Yeah. I want to read just a little bit from the introduction to the book. Right at the end of the introduction you're quoting a Soviet born émigré who teaches in a university deep in the US heartland and that he stresses the urgency of Americans taking people like her seriously. So she warns,

"You will not be able to predict what will be held against you tomorrow. You have no idea what completely normal thing you do today or say today will be used against you to destroy you. This is what people in the Soviet Union saw. We know how this works." Then you write, "On the other hand, my Czech émigré friend advised me not to waste time writing this book." This is getting to the resignation or cynicism element. So he said, "People will have to live through it first to understand, he says cynically. Any time I try to explain current events and their meaning to my friends or acquaintances I am met with blank stares or downright nonsense." And you write, "Maybe he is right, but for the sake of his children and of mine, I wrote this book to prove him wrong."Now one of the things I've seen in just the readings that I've done over the years, and I think you mention this in the book, that even in some of the quotes that you include at the beginning of each chapter, that for a lot of people who went through this experience in Eastern Europe or in Russia or even in Nazi Germany, they couldn't have imagined that it could have happened there. So you have this society that seems to be stable or seems to be immune to a certain degree to what might imaginably come. And then it comes and people are introduced into what could be called a completely new reality, an alien reality that is completely outside of their previous experience so it hits them like a railroad train.

And then you have the people on the outside looking in, who might have some idea that something over there is going wrong. Of course there were always criticisms of the Soviet Union and the communist world from the west but even then, I think even from those critics, they didn't and couldn't really actually know what it was like to live in that kind of system. So now you have the experience of all of these émigrés and people who have lived through it and you quote their thought that people here just don't get it. "I try to explain it to them" and the one at the end said, "Well they're just going to have to live through it on their own." Could you say anything about that phenomenon and maybe why you think that it might be possible to get through to people, the information they need to take this warning?

Rod: Well I can tell you that the Czech émigré and I have stayed in touch. We email almost every day. When Live Not By Lies hit the New York Times bestseller list he wrote to me and said, "You know what? Maybe I'm wrong. I didn't think anybody would buy this book." He said, "You'll have to forgive me. I am an Eastern European and we're very dark." But it did give him a little bit of hope and I'm just happy for that.

But it is human nature that we don't want to think about the worst that can happen. If we go back to the bible, the prophets would come warn the people of Israel in the old testament, "You've got to change, you've got to change. Bad things will happen." They wouldn't change. Bad things happened and they learned their lesson. This is a constant of human nature. Solzhenitsyn said at the beginning of one of his early editions of the Gulag Archipelago that one of the great mistakes people can make is thinking what happened in Russia couldn't happen in their country. He said given the right set of circumstances it could happen anywhere on earth.

Similarly, Czesław Miłosz the great Polish intellectual who defected from Poland, in his book The Captive Mind, I quote him in Live Not By Lies here, he said that the people of Eastern Europe woke up one day rather unhappily to discover that the kind of ideas that were only talked about in coffee shops and intellectual circles 20 or 30 years earlier were suddenly ruling their lives. This was Milosz's way of saying that you've got to pay attention to what is discussed in intellectual circles because when certain ideas take hold among the elites then that's how they really gain traction over people's lives.

I can understand why the people who were so traumatized by communism are acutely aware of similar conditions happening here today and also about how Americans, because our historical experience has been one where we've never really had to deal with ideological radicalism and we've never been invaded - communism was forced on the people of Eastern Europe - we just don't think it can happen here. They're trying to tell us, no actually it can and if you're going to stop it then you need to be aware of where these ideas and this way of thinking goes.

So just before we came on to talk with y'all, I was reading something in Quillette magazine about a racial panic that's happened at Haverford College's campus in suburban Philadelphia and it is straight out of something that you could have read about Bolshevism. It doesn't have anything to do with Marxism/Leninism but this idea that a radical group that was a vanguard that was extremely insistent on its ideological point of view, even though the leaders gave them everything they demanded it still wasn't enough and they managed to intimidate any dissenters on the faculty and among the student body at this very liberal college and to silence! And now nobody knows what's going to happen at this college.

Again, a very liberal college that has been radicalized very quickly and totally disrupted by a powerful vanguard of radicals among the student body that met no effective resistance from the school's leadership. You read this sort of thing and then you look at what happened in Russian history and you begin to understand why these émigrés are so anxious.

Elan: Well that's a very interesting reference to that recent development because as you say in your book Rod, even if the totalitarianism doesn't look and seem exactly the way it was presented in Bolshevik Russia and Soviet Russia, there is still some version of it that is making itself manifest in today's west. There are very crucial similarities that we need to take a good look at because, as you were saying earlier, there is a cultural memory that we can learn from, that we can listen to, that if it doesn't describe everything exactly in the same way, does get at the very heart of the matter.

So in your book there is this kind of intersection I would say, between societal changes, political changes, but also religious ones where the individuals that you interviewed had survived their experience of communism and persecution through a religious, Christian faith that kept them on the straight and narrow. This is I think a very interesting and important feature of your book, which was that this is a kind of spiritual battle that these people experienced and chose to face but could only have done so in many cases, through their faith. I wonder if you could speak a little bit on that and how that forms your own views of things.

Rod: Right. One of the lessons I got from talking to people in these different countries is that really the only way to have survived totalitarianism and keeping your integrity is to believe in something higher, something greater than yourself. Now it is the case in Czechoslovakia, Václav Havel and his circle were all atheists. Václav Benda and his wife Camilla - they're also in my book - were the only Christians in Havel's inner circle but in most of the other countries the dissidents were often believing Christians and they were able to withstand all the state through at them because they believed that there was an ultimate reality beyond the material world and faith in that ultimate reality is what got them through.

This one professor I spoke to in Warsaw had a really good analogy or simile to describe this. He described human existence as like a kite. He said a kite can go very high in the air if it is connected by a string to someone on the earth but if you cut the string the kite, however high it is, will spiral to the ground. He said that's how it is for us and god. If humanity is connected to the transcendent, to god, the ground of transcendence, we can achieve great things. But if that line is cut then we make a mess of it.

I think he was talking about that in connection to the phenomenon you just brought up about how this belief in god, not only in god in general but in the Christian god and in transcendent values, which is also something that Václav Havel and these others believed in, if not god, they believed that some things were true and that communism itself was a massive lie, a system built on lies about ultimate truth. But the way you prove things are true - this is a very Kierkegaardian point I guess you might say - the way you show things are true is by being willing to suffer for them and the fact that Christianity teaches the ultimate meaning of suffering, that if you are willing to suffer and die for Jesus Christ ultimately but also for the truth that Christianity proclaims, then that is how you demonstrate to others that these are truths worth living and dying for.

In the book I talk about the great Terence Malick movie that came out earlier this year called - what is it?

Elan: I was just reading about it.

Rod: A Hidden Life. I can't believe I can't remember that. But it's based on the true story of a man who faced totalitarianism in Nazi Germany, Franz Jägerstätter. There's a moment in the movie - I don't think this really happened in Franz's life but Franz goes to a church there were an artist in the village is painting images of the bible on the side of the church wall and the artist tells him, "Yes, this church is full of people who admire the life of Christ and admire these stories but they're just admirers. When it comes down to it and they have to suffer for their faith, then they go away. Jesus didn't call admirers, he called disciples. The way you prove your discipleship is by being willing to suffer."

This is something to pull out away from Christianity specifically. This is why I think that in the United States, whether we're Christians or not, are particularly susceptible to a form of totalitarianism that proclaims itself and institutes itself by manipulating status and comfort. It's more of a Brave New World than Orwell's 1984. If we are not willing and able to suffer for our principles, much less our religious faith, then we're going to be smashed by a system that is prepared to make us suffer even something as simple as a loss of status or a loss of a job. We'll roll over for it.

Adam: I think you talked about this in your book as well, the state of the American populace and just the way that consumerism has influenced society to such a great extent, that any kind of discomfort or anything that is difficult or requires suffering is bad. Because it requires suffering it's bad essentially, which is a fundamental contradiction to the actual reality and to Christianity itself. It's a contradiction of what Christianity preaches. In order to bring something about you have to suffer for it. That's the only way that you're ever going to really value whatever it is that you have, is if you actually sacrifice for it. If you don't make any sacrifices for it then you don't really care about it and you did nothing to earn it.

That was something that I really enjoyed about your book, the way that you were able to bring that out and I guess reveal the extent to which there is the social justice warrior aspect where they are critical of suffering but only in a certain respect, only when it pertains to specific minority groups. Their suffering is paramount and everyone else is not non-existent...

Harrison: Irrelevant.

Adam: Yeah, irrelevant.

Rod: It doesn't matter.

Adam: Yeah, it doesn't matter because they're the power holders even though those are completely contrived categories of people. I think you also made that point in your book where the older white male who's living in poverty versus the Ivy League black lesbian professor, one is clearly better off than the other but still the white man is more privileged because he's white. That's totally irrelevant.

So there's that aspect of it but there's also the consumerism. I really like the way that you bring it out to say it's getting hit at both fronts, the value of suffering and that is dangerous.

Rod: Right. You know, one thing that really shocked me doing research for this book is reading about when the Bolsheviks came to power, the way Marxism/Leninism decided who was good and who was evil only on the basis of social class. So a quote in my book, this order that came down from a official from the predecessor of the KGB, directing the red terror, the mass terrorism and murder campaign that the Bolsheviks used to consolidate power. He told his agents, 'When you go out into the field, don't actually look for guilty people on the basis of what individuals did. Check their social class. If they're bourgeoisie, the middle class or rich farmers, kill them. If they're not then they're on our side.

Well you take that same mentality and apply it to our own social justice warriors where they decide the guilt or innocence of a person. It doesn't depend on what the individual actually thinks, believes or has done, but only on their identity. You can justify any amount of cruelty on the basis of that. And we're accepting it! That's the thing that just blows my mind! People are rolling over for it, maybe because nobody has told the stories of how this was used in the communist countries to suppress free thought and free exercise of religion and all forms of freedom.

I think one thing that we can look at from our own history is the way Martin Luther King and the civil rights marchers and leaders were willing suffer for the things they knew to be true and the fact that they were willing to suffer without striking back deeply, deeply struck the consciences of most Americans and led to radical and positive social change. I do wonder though to what extent that sort of protest would work in America today given that we are so post-Christian. The civil rights movement in the 1960s was led by black preachers and they spoke in the cadences and the symbolic language of the bible.

Well that's gone. The capacity for Americans to hear that kind of rhetoric and to understand the symbolic language of what the civil rights marchers were doing, we seem to have lost that. So I'm not quite sure to what extent the willingness of people to suffer, how that will affect a social change. But we do have - in the book I talk about this too - Václav Havel's story of the green grocer. It's a fable he told in a very powerful essay he wrote in 1978 I think it was, called The Power of the Powerless. Havel was the leader of the dissidents in Czechoslovakia.

He told a fictional story of a green grocer. Let's say the green grocer under communism has to do what every other store owner does and hang a sign in his window that says, 'workers of the world unite', a Marxist slogan, just to avoid trouble, just to go along to get along. Well what happens, says Havel if he decides one day not to hang the sign, to take the sign down? What happens to him? The authorities come, he loses his business, he is an outcast, his kids can't go to college, he can't travel and so on and so forth. He takes a serious hit. But what he has done by his act of resistance, as simple and as small as it was, is to show to everybody else that it is possible to live not by lies, that is to say to live and survive without having to say that you agree with the system, that you accept the lies that you're supposed to tell so you can get along in the system. Most people will look at him and think maybe he's a fool or a bad man for doing that, but there will be others who see his protests and realize, 'You know what? These are lies we're living in.' And that will grow and grow and grow. His act of integrity.

I think that we're going to have to see something like that here before this madness stops. We're going to have to see people willing to sacrifice themselves to inspire others to stand up as well. One thing I believe that people, whether they're people of faith or people who believe in old fashioned liberal ideals have to do is to make it easier for people within corporations, universities and these structures to stand up and even sacrifice their jobs. One way we can do that is by supporting them, standing up for them when they do that and also standing up not just rhetorically in public but by giving money to help them and their families support themselves when they make these moves.

Harrison: That brings to mind a couple of things. One of my favourite books was written by a Polish exile, Andrew Lobaczewski. He was a psychologist in Poland and he wrote a book called Political Ponerology which was his attempt to account for the phenomenon of totalitarianism from the perspective of the psychological science that he acquired before the institution of communism in Poland. One of the things that he writes about in his chapter on religion and the system, which he calls pathocracy, basically meaning the rule of the sick or the ill or the diseased because he saw the essence of communism as experienced in the eastern bloc as the product of diseased minds. We can get into that if we want later. He said that when it comes to religion, if a country falls to a homegrown rise of a revolutionary totalitarian movement, that the responsibility for that pretty much lies with the church, that they have failed their function in society if they've allowed the society to become weakened to the point where it becomes susceptible to that kind of thing.

But, he said, once it is there, religion then becomes the sine qua non of not only resistance but survival. It's a very dry work with stilted, chunky writing - clunky writing - but I'll paraphrase something he wrote. He said something like 'after some years in a system like this, religion ceases to be just tradition, dogma and one other negative aspect associated with old religion that's dry and ossified and not doing its job, and it becomes faith' because it is that the suffering caused by living in this system, the atomization, the setting people against each other, creates the crucible of suffering that then not only necessitates a life of faith but it almost forces it out, like striking a piezoelectric stone or something. By being hammered, something lightens or awakens within.

Some of the accounts that you give in the book of some of these Christian dissidents are just beautiful, whether it's a short anecdote or a long story or a long conversation, two come to mind. One is the guy who had a realization when he was arrested that it was the greatest thing he could do in life would be to die for god, for his faith, for the truth.

Rod: Silvester Krčméry. That was who that was. He was in Bratislava.

Harrison: I think he was in the car with his arresting officers and he just started laughing and they weren't very pleased with that. That also reminded of a story that Andrew Lobaczewski tells about his own arrests. He reports that he was arrested and tortured three times, I believe. On the fourth time he was arrested he was given his passport and told to leave the country. But on the first time that he was arrested he didn't have any of that clarity. The whole experience was almost like a dream for him. He was arrested. I can't remember if he was tortured during that first arrest but afterwards they let him go just as arbitrarily as they had arrested him and he was just left thinking - I think the quote that he gives he said something like "God, where are you in this world? What's going on? How can this happen?"

But on the second or third time that he was arrested and tortured he accessed this inner strength and confidence and out of his interrogators, he looked at the one that was the head guy, the meanest one, looked him directly in the eye and said - paraphrasing - 'I wonder why it is that people in your profession end up in the mental institute after so many years." {Rod laughs} The guy looked at him and said, "What are you talking about?"

But it was that confidence that he showed and actually cracking a joke, even if it was at the other guy's expense, the guards then actually treated him pretty well from then on and let him go some days later. So the inspiring thing about these stories and the ones that you share in this book is the inner strength that faith can and did provide for all these people. It not only let them survive but it gave their lives meaning and they were the ones who could sit through solitary confinement and torture and to not only be broken by it but to actually be refined by it.

Rod: Yeah, that's it. What is the difference between those who were refined by it and those who were broken by it? That would require a longer book but I did write in Live Not By Lies about the experience that Timo Prishka had. Timo Prishka is a Slovak photographer who was a child when communism ended, a little boy, so he has no real memory of communism, but he ended up doing a book, a photographic essay and interviews with elderly Slovaks who had been put in prison for their faith back in the 1950s and 1960s. He went to visit them and take their portraits and talk to them and it really changed his life Timo said because most of these people were still quite poor. Some of them had been tortured and lived in solitary and so forth, but they all told him that the times they were in prison were among the most meaningful times of their lives because that was when they had everything taken from them. That was when they had to fall back entirely on god.

Timo began to understand from the people he was talking to who just has this inner light glowing, how rich their lives were and how impoverished his own life was even though he had vastly more freedom and more material wealth than his parents' and grandparents' generation had but he didn't have what they had. He said that it led him to a deep inner repentance.

Similarly Solzhenitsyn in the Gulag Archipelago writes these incredible words, "Bless you prison." This is a man who had the worst that the 20th century could throw at anybody, absent the gas chambers, thrown at him and yet he looked back on it as a blessing because it awakened his moral conscience and his religious conscience.

That orientation towards suffering is the only way we can survive it, I think, without being cracked. Here in the United States, I really don't see anything like the Gulag Archipelago coming towards us. It may one day, but I don't think it's going to happen. I don't think it really needs to because we're so soft about suffering and so unused to it and we've been so acculturated to a culture of middle class convenience.

I'm as guilty as anybody else. I'm a hobbit. I like to sit on my couch and drink my nice tea and have all the creature comforts, but I think these things are going to be taken from us. In fact I think this year of Covid has been, in a way, a dry run for a future of deprivation. I'm one of these people who believes that Covid is real, don't get me wrong here, but I think that we have been shown that our normal lives can be radically disrupted by things we can't control and if we can't manage to get through this in a stable way and not only survive it but thrive it, how much worse will it be when there are things that are actually done to us that make life much harder for us?

To be honest, I've gone back - this year with the lockdowns first started we couldn't have church - I'm Eastern Orthodox and we couldn't go to liturgy and there were some people in our church who were understandably really upset by this because they missed having church. And I felt the same way about it because church is such an important part of my life and my family's life, but I went back to the stories that I had read of the Eastern Europeans and the Russians who suffered so much more. It wasn't a case of "Oh quit feeling sorry for yourself. It could always be worse" though that's true. It was rather that these people had to learn how to deal with this in the long run. Not a single one of the dissidents I've talked to ever thought they would live to see the end of communism so they had to build a life for themselves, a life of integrity and a life of faith believing that they were always going to live in captivity.

I think that there's a lot we can learn from that about learning how to abide in suffering.

Elan: Well, along those lines, there were these very proactive people that you discuss in your book, Kolakovíc, who was a gentleman who could see what encroaching communism was going to do in Eastern Europe during the 1940s I believe and was able to talk to people, create networks of discussion groups and classes and social meetings and really had an incredible vision for how to offset the negative effects of communism among the faithful and among people who were just open to his message it seemed.

I thought that there was a very powerful message there in your discussion of his See, Judge, Act and his networking ability and his ability to see so far ahead and plan for those times with individuals who shared his vision for networking, for keeping strong and keeping faith in groups. I wonder if you might expand on that Rod and talk about that network that he created.

Rod: I'm so glad you asked about Father Kolakovíc. He's this unsung hero of the Cold War. I knew nothing about him until I went to Bratislava to speak at a conference and to do some research on the underground church there for my book and I learned that he was the reason.

He was born Tomislav Poglajen in Croatia - it's his home country -and became a Jesuit priest. In 1943 he was there in Zagreb doing anti-Nazi work and he got a tip that the Gestapo was coming for him so he slipped out of the country and went to his mother's homeland, Slovakia nearby and adopted her last name, Kolakovíc and he began teaching in the Catholic university in Bratislava. Because earlier in his career he had trained in the Vatican to do missionary work in the Soviet Union, he understood deeply the communist mindset and that gave him insight into what was likely to happen in Czechoslovakia after the war was over. He told his students, "Look, the good news is the Germans are going to lose this thing. The bad news is the Soviets are going to be here. We're not going to be able to get rid of them and the first thing the communists are going to do is come after the church. We have to get ready."

Well the catholic bishops there didn't want to hear this. They accused him of being an alarmist, of upsetting people for no reason but he didn't listen because he knew what was coming. So what he did was organize these student groups. They started out as prayer groups but they were also discussion groups and they were modeled after a program that he had learned about, the Young Catholic Workers I think they were called, in Belgium which was a social movement to get working class catholic youth together to talk about social problems and social reform. They had a model called See, Judge, Act. It was a simple model for how to analyze social problems and how to talk about them as Catholics, 'What shall we do?' and then make a decision to act.

Kolakovíc brought that to his own groups. He called them The Family. In Slovakia he started one in Bratislava and they spread quickly all around the country. Each town of any size had a chapter of The Family. All they would do was this: they would come together for prayer but they would also come to hear lectures about economics, sociology and so forth and to apply their faith and their knowledge to analyzing what was happening in the real world there in Slovakia. For them, that meant also preparing for the coming of totalitarianism at a time when the church would be suppressed.

So they would learn practical things too, like how to resist an interrogation. You can imagine to the bishops this sounded crazy but sure enough, when the iron curtain fell and they kicked Kolakovíc out, the first thing the communists did, the Soviet puppet government did come after the churches and they neutralized the priest because they thought - and it was a reasonable theory - that Catholicism is a hierarchical religion and if we can just get the priests and neutralize them, then the church will be suppressed.

Kolakovíc knew that how they thought and so all the lay people that he had helped prepare for leadership, they took the ball, they and a few priests who had allied themselves with Kolakovíc built the underground church and they were the only meaningful resistance to communism for the next 40 years.

I dedicate Live Not By Lies to Father Kolakovíc because I think that were are in a Kolakovíc moment here in the United States now. I don't know when the iron curtain or whatever the equivalent will be, is going to fall. It may be a slow noose sort of thing around the church and around people who dissent from the regime, even if they're non-religious, but I think it's going to come and I think that we have to right now start building these networks of groups who can See, Judge and Act. I think it's important too that in Kolakovíc's world it was young people who took the initiative because they were the ones who were open to his ideas and they were the ones also who didn't have a lot to lose. They could hear what he was saying because they weren't so invested emotionally and otherwise in the existing order. I think people my age - I'm 53 now - people my age and older really don't want to believe that bad things could happen here. Young people though who don't have that same sort of investment, I think are more open to talking about these things.

I can also say real quick that Viktor Popkov is somebody I mention in Live Not By Lies. He's a Russian who became a Christian in the early 1970s and ended up going to prison for his role in the underground church in the late Soviet period. Viktor Popkov told me as a young man he was not raised with religion at all but he was so miserable with the sterility and the crushing boredom of life in the Soviet Union in the 1960s. He began to search for the meaning of life. The only people he saw around him who seemed to have any kind of connection to something living were the young Christians.

Similarly in Russia in that era there was a priest I write about in the book called Father Dmitri Dudko who was a very brave Orthodox priest who began to speak out openly. He wouldn't challenge the system directly. That would have got him sent to prison straight away, but he just talked about the meaning of life and that life does have meaning and purpose. People began to come, all kinds of people, people who were Jewish, people who were atheist. They just wanted to see this man who had something. He was in touch with something beyond himself that gave them hope. I think that we're going to be looking for the same sort of people here eventually.

Harrison: Rod, you don't talk about this in the book but it just came to mind when my mind was free associating while you were talking there and the question came to me, during this period in the Soviet Union, were there similar cells of resistance like in the Muslim parts of the country? Have you heard anything about that?

Rod: I haven't. I wouldn't be surprised if there had been but I just haven't heard about it. I wrote the book as a Christian for Christians, but I'm finding, to my surprise and delight, that in this country there are people who aren't Christians who are embracing the book. Bari Weiss, the secular liberal Jewish writer who resigned from the New York Times in protest of the way wokeness is taking over that newsroom. She has become a fan of the book and recommended the book. Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying who have a popular podcast, The Dark Horse Podcast, are both secular leftists, atheists but they have embraced the book too because they themselves have had to live with soft totalitarianism that drove them out of their college, Evergreen State in Washington.

So I've just been delighted to call these people my new friends and allies because this is the sort of thing that we're going to need. In Live Not By Lies I talk about how Camilla Bendova in Prague as well as a man named František Mikloško in Bratislava talked about how you needed allies anywhere. There were so few people in those countries who were willing to take a stand of any kind. Most everybody kept their heads down and tried to stay out of trouble.

So when you found somebody who would do it, whether they believed in god or not, you needed to be friends with them and to find out what you had in common and how you could help each other. I think we're in a similar situation here.

Harrison: In that second part of the book where you talk about all of these things that can and should be put into practice now in order to have them, like Kolakovíc was able to do to get them started, so that they were established by the time they became absolutely necessary, one of the things is that you mentioned in passing these small church groups, small church meetings among the lay members of the church. I've got a page number here. Let me just find what I'm thinking about in the book.

Rod: Let's turn to scripture and...

Harrison: Yeah, let's turn to scripture {laughter}...In standing in solidarity is the chapter on page 167. You quote - I'm going to butcher this name - Ján Šimulčík...

Rod: That's perfect. That's it. Ján Šimulčík.

Harrison: Great. He says at the bottom of the page,

"When you ask that question ('Why did you get involved?"), you are really asking about where we find the meaning of the underground church. It was in small community. Only in small communities could people feel free."Maybe talk about that, what he meant by that and how we can apply that to our lives now, today, here.

Rod: Yeah, because we are incarnational creatures. The abstract ideals have to become real in the material world by living them out. Ján Šimulčík told me this story standing in an underground chamber in Bratislava. It was incredible how we got there. He took me to this ordinary house in suburban Bratislava that had been used by the underground church. The man who lived there back in the 1980s was a catholic priest, secretly ordained, but he was disguised as a worker. And in the basement of this house, actually under the basement there was a tunnel and he took me into this tunnel. It was behind a hidden door. You went into this tunnel and you came up in a secret room that was behind a basement wall. In this tiny chamber there was an offset printer - it's still there - that some evangelicals in the Netherlands smuggled into Bratislava to help the underground catholic church back in the 1980s.

For 10 years in that little room they printed prayer books, gospels, catechism, things like that, to keep the underground church going and they were never discovered. But it was an elaborate movement or elaborate scheme to do this. Šimulčík was part of a small group of catholic college students who had come to the house every week to bind together the things that had been printed by Samizdat and he didn't even know - none of them knew that this was happening in that secret chamber under the house because that was how it had to be. If any of them had been arrested they would have been tortured and sent to prison. The church had to protect itself.

Šimulčík said, and he goes on to say in the passage you were talking about how that, as a college student, is what helped his faith become real and helped him to feel free, that he wasn't just alone, that he had three or four other young men who were willing to take the same risks that he was taking to serve god and to serve the underground church, people that they might never know because they couldn't know them. But they had a mission, they had a reason to risk their lives and their freedom and that gave them freedom. He says that this is the only place he felt free, when he was in these small groups with people who shared his faith and who shared his commitment to risking their lives for something higher.

I think that the thing that totalitarianism, certainly communist totalitarianism, I guess any totalitarianism, is keeping people divided and atomized. Hanna Arendt said in her book, the origins of totalitarianism, when she went back to try to analyze after the end of the Second World War why so many Germans had given themselves over to Nazi totalitarianism and why so many Russians had embraced Bolshevik totalitarianism, the number one reason was the loneliness, the mass loneliness of people and the sense of atomization, of not being connected to anybody else, to any institution, to any way of life. The Totalitarian movement slipped in there and gave people what they were longing for, that deeper sense of meaning and solidarity. It was fake but it was something.

What Šimulčík was saying there, about the small groups, is that this was something real. The state only wanted people to have solidarity in ways that it could control but it really kept them atomized and afraid of each other. But Šimulčík said when he was there working with those others he knew that they were real because they were all willing to suffer - again, there we go - to suffer or rather to risk suffering in prison for the sake of their cause and that was real freedom.

I think that in our case, we are clearly a society that is just completely eaten up with loneliness and atomization and this has not happened because the state has forced it on us. It has happened because our economy and the way we've chosen to live and the technology we've embraced has brought this to us. I'm as much a victim of it as anybody else. I'm sitting here in my house and before Covid started, I'm connected to a lot of people all over the world every day by the internet but I can't tell you who my neighbours are. And that's on me. That's my fault. Nobody has forced that on me and I know a lot of people who are like that.

But I think that the hardship of soft totalitarianism, when it comes, will force those who want freedom, who want some reason to live higher than themselves, to seek each other out and to build these bonds of real community.

Finally Václav Benda - I don't talk about it in Live Not By Lies but I did talk about it in my previous book, The Benedict Option - Václaw Benda, his wife Camilla is in Live Not By Lies, under communism he realized that the best way he could resist it was to try to rebuild a sense of community that totalitarianism had destroyed. So he came up with this idea he called the Parallel Polis. He said, "In Czechoslovakia we can't have a real politics, a free politics where people can choose to participate in the order and have some sense of democratic accountability, but that doesn't mean that we have the right as Christians or as individuals, to sit at home and submit to it." He believed that Christians and others should create a parallel community of people that was based on actual consent and participation, not to replace the communist system because that wasn't possible, but rather to remind people who they were, to remind people what it means to be human and what it means to be a neighbour.

So for Václav Benda, a simple act of people getting together to share a meal was a political act because it was something that would help rebuild a real community.

Elan: Well Rod, your book is really impressively broad in some ways because you take some time to discuss the social credit system in China and in the US and what big tech and surveillance technology and all the modern conveniences that we've become so used to relying upon are doing to us. So what you've done I think, is to create this much larger picture of totalitarianism in a few different forms and how it has been manifesting.

So what's interesting to me is that you have the radical left ideological craziness that's been on display for the past six or so years, if not more, and then you also have the top down corporatocracy and big tech surveillance and that whole element. Something that may fall outside of your book a little bit is the mass vandalism against institutions of Christianity, particularly in Europe, but also some in the US and also this move against calling Christmas, Christmas. I guess the point is we're seeing something coming at us at several different angles that are all quite pointed.

I'm 49 years old, you said you're 53. This is a very different world I feel like I'm living in than when I grew up. So what, if anything, can we say is actually occurring? Is the whole world going bonkers at around the same time? Are all of these developments interlocked or interconnected in some fashion? I was wondering what you thought all this is.

Rod: It's a huge question. If it makes you feel any better, even the people who lived through communism who can see that something big is coming, even they can't say exactly what it is and they freely admitted that to me. This one Slovak priest said in some ways this is more difficult than communism. He said under communism it was easy to tell what was good and what was evil and the gospels shone a clear light through that darkness. But now the light of the gospel only hits fog. I think part of the reason is this new totalitarianism does mimic the best parts of Christianity and the best parts of liberal humanism.

René Gerard, the 20th century cultural critic, just a brilliant intellectual, he wrote in the year 2000 - I quote him in the book - as saying that this concern for the victim which is something that Christianity has always had and that since the enlightenment period, which was a secularization of Christian moral values, our democratic societies have had at an increasing level, this concern for the victim and for the oppressed, has become so intense that it threatens to become something totalitarian, the word that René Gerard used and a form of constant inquisition.

So when you have, for example, this abuse of language of the term anti-racism, the book by Ibram Kendi, How to be An Antiracist has become a must-read for so many within institutions and companies. Kendi has this credibly Manichaean and simplistic idea about race. Either you're anti-racist as he describes it or you're a racist. There's no middle ground. There's no ambiguity. He's had black intellectuals like Thomas Chatter, T. Williams and John McWhorter call this out as clearly simplistic and even totalitarian. But this is what's going on now! But the word anti-racists is to introduce in a highly ideological way, in a way that George Orwell talked about, to frame the discussion.

So if you stand up to anti-racism programs then you by definition must be an racist. This is a way of manipulation to make it impossible to think critically about what is being proposed because nobody wants to be a racist, right? So it's a brilliant way of manipulating the discourse and manipulating the way people understand reality.

In my book, this Polish professor in Warsaw told me that it's something he worries about a lot with his own students of the post-communist generation. He said, "We all under communism could see how the authorities were changing language and manipulating language, redefining basic concepts to control us and there was that consciousness of what was being done and being done so ham-handedly almost as a form of defense." He said, "Kids today have not had that experience. They're so much easier to manipulate, so much more susceptible to this ideological manipulation."

You were talking about the social credit system. I'm glad you brought it up because this, I believe, is the main way that soft totalitarianism will manifest itself and work in our society. For those of your listeners who don't know, the social credit system is something that the Chinese have developed and implemented or are implementing in their country now. What they do is they take all the data that is generated by ordinary Chinese people using their smartphones and in that increasingly cashless society you have to use your smartphones to do everyday purchases.

So they're taking all the data from smartphones, from using the internet and from GPS coordinates, from cameras on the street, and they're feeding it all into a main computer system. This is slightly simplistic, but this is how it's working. And it keeps a constant tally of each individual Chinese citizen, of whether they've done the right thing, socially positive things or socially negative things. If you are socially positive, meaning you do things like download the speeches of Xi Jinping or other things that can be measured by the data, by the algorithms, you get a higher rating and you get better jobs, kids get access to the best universities and so forth. If you have a lower rating, which you get by doing things like going to church or spending time or being friends on social media with other bad people, you get a lower rating and suddenly you find your privileges constricted.

It can even go to the point where you can be shut out from buying and selling in the economy because if all the purchasing has to be done digitally in a cashless economy then shutting you off from the economy is a matter simply of flipping a switch. Well this is how the Chinese do it. It's interesting. They can manage to have a police state without having to send the police to people's doors to yell at them.

We can do this in America too. The same data are being harvested, not by the state in our case, but by major corporations - Google, Amazon, and so forth and it's simply a matter of deciding to weaponize that, to marginalize people who are dissenters, who are dissidents, who are deplorables and so on and so forth, who don't fit the idea of what the people who run these companies think is socially positive. I think it's only a matter of time before that happens.

I saw just last week somebody was putting on Twitter, there's an app you can get for your phone that will change the colour of social media text and social media messages if the app's algorithm decides that the person writing it is anti-transgender or pro-transgender. It seems so silly. It's called Shinigami Art. It seems so silly but here you have someone, if they've made their mind up that they don't want to have any contact at all with any impure person who might have said something that is anti-transgender, all they have to do is see the colour of the text. Somebody could be writing about nothing having to do with transgenderism but the colour of the text will mark them out as deplorable, as enemies of the people, as bigoted, whatever you want to call it. The fact that these things exist and people are beginning to rely on them as tools to determine who is pure and who is not is how totalitarianism is going to come here, even if the state never gets involved.

I think the state will get involved. I think the state will get involved at some point but this is one reason why it's so hard for Americans to recognize this is totalitarian. If you had an agent for the government from the FBI show up at your door and say "Sir/Madam, we'd like to install this speaker in your house that will allow you to order things conveniently to be sent to you just by using your voice, but it will also be listening to some of what you have to say." You would tell the government to go take a hike, but when it's sold by Amazon and it's sold as purely consumer convenience, we not only welcome that into our houses, we'll pay for it!

I'm a bit on my high horse {laughter}.

Elan: Amen!

Rod: Once you start reading this stuff like Shoshana Zuboff's book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism and you see how ubiquitous it is and how we have just been so anesthetized into accepting this into our lives to the point where suddenly you can't do without it, we get to see how deep we are.

Harrison: And those kinds of things are already being, I'd say, rolled out on a trial basis for extreme cases. I know people online or have heard of people who have been totally locked out of PayPal or YouTube, people who relied for their income on either PayPal or YouTube or both, or Patreon, who have just gotten blocked, for political reasons. "You have said something that we don't like you saying so we are going to block you from being able to receive money."

Adam: It's soft totalitarianism without the state. You can still do it just by virtue of big business.

Harrison: But the way they're able to get away with it right now is because I'd say for some of these individuals that I'm aware of, most people would probably think it's a good thing that they're being cut off, right? It's a good thing that they're being banned. That's not the kind of person that I want to have free speech. For some cases I can kind of agree with them. I'd say I can kind of see why you'd want that person totally cut off, but at the same time I'm totally against cutting them off because that opens so many doors. It sets the precedent and that's why I see it almost as a trial run. "Okay, let's see how much we can get away with. Can we actually cut people off from financial institutions, from being able to receive money digitally? Can we ruin their lives like this? Well yes we can and it didn't cause any big waves because who's going to care about some loser guy on the internet who makes offensive stuff and who no one knows, who probably only makes $20 grand a year, not a big personality, not a big celebrity. Who's going to care? Who's going to find out about it?

But that sets the precedent and then you look at a country like China where this kind of thing is already institutionalized and you see those two things and that doesn't give much hope for this never happening.

Rod: Right. And you know in China - this is the thing that blows my mind - the social credit system is actually popular.

Harrison: Yeah.

Rod: People want that. And why do they want that? Because communism destroyed all traditions, all social life and you can't live that way. You don't know who you can trust anymore and Chinese living there today will say at least it tells us. You can look at somebody's social credit rating, it's all public. You know who you can trust. That's seems crazy to us but we don't know what it's like to live in a society where civil society has been completely destroyed and people need some basis to know that they're not going to be cheated.

We're talking about alienation and atomization here. Well we don't have it to the extent that the Chinese did but we're getting it more and more. There are people who will want to know or feel like they want to know that the shop they're going to, that these are decent people, which is how you get things like Havel's green grocer putting 'workers of the world unite'. Well today the Havel's green grocer sign might be a pride flag or you name it, something to say that black lives matter, something like that, to say that "I'm good. I'm pure. Don't harm me."

You were talking about bad people being demonetized. I read recently that in the UK some far right activists have been denied bank accounts. I'm talking about just ordinary bank accounts for checking and they weren't able to get access to it because the banks have the right to refuse your business. Well these are awful people. They say racist things and they're not the kind of people that I want to see thrive, but you're right. If these people are not allowed to have bank accounts that means they're not allowed to participate in the modern economy, where do you draw the line? Today it's them. What about tomorrow if it's people who go to church or people who vote Tory? You name it. Once the principle is established there's no stopping it.

Adam: And it can also serve to bolster that person. I can't think of a specific example, but let's say an actual racist individual was deplatformed and was disallowed a basic bank account. They were not allowed to get one.

Harrison: That can radicalize a person.

Adam: Yeah, it can radicalize a person by saying, "Look, I'm justified in saying what I'm saying because I'm not allowed to say it. That proves that I'm right." That's the exact opposite of the thing that you want to do if they're crazy. If they're just crazy.

Harrison: You want them to speak as loudly as possible.

Adam: Yes. Let them talk to everyone because then everyone's going to see that they're crazy and it's not going to go anywhere because they've just outed themselves as crazy. But by denying them a platform you're actually creating the problem that you're setting out to get rid of and you have no one to blame but yourself.

Rod: I think you're right about that. And you know, I think one of the most important moments culturally in this country on the road to soft totalitarianism happened in October 2015 at Yale University. You guys might have seen this. You can see it on YouTube. That was when they had this big controversy on campus about Hallowe'en costumes. The university had sent out something saying be careful about what you wear. Don't wear offensive costumes. Erika Christakis who is a professor there, she and her husband Nicholas also a professor were house masters of one of the residential colleges and she just sent out an email to the members of that college saying, "Really? Is this something that the university should be concerning itself with? Telling adults what they can and can't wear on Hallowe'en?"

The students came against her so hard, they accused her of being racist and not loving them, not caring for them. It all came down to this thing you can see on YouTube where her husband Nicholas went out on the quad at their college and tried to engage this large group of protesting students in a reasonable, rational dialogue about this. He was a baby boomer. He was doing just the model of rational discourse, listening to them, offering feedback and trying to engage them. They weren't having it. This mob of young people just shrieked at him. Some of them sobbed. They were in a total moral hysteria. They cursed him. Of course Yale university sided with the students against the Christakises. And that showed me right there that when the people who run institutions, who have the power to enforce norms, when they yield to the mob, we're done for.

I think that the sort of people who care about being called racist and don't want to be racist or bigoted, when they are run over and there's nothing they can do to redeem themselves in the eyes of these activists, what it does is empowers the people who actually are racist and who don't care if you call them a racist. They're proud to be racist. Those become the people who end up being seen by many others as brave because they stood up to the mob. It's a really bad situation for people like me and you who want to live in a decent, honourable, old fashioned liberal society where people are free to dissent without losing their jobs and without having their lives threatened and their families put at risk.

Harrison: Rod, how are we doing for time?

Rod: Can we go about five or ten more minutes?

Harrison: Sure. Did either of you guys have a final question?

Elan: Well, just to comment really, and that is that in your discussion, getting back to the area of suffering for truth, that your explication of it is very nuanced, which I appreciated; the idea being that while some suffering may be involved and self-sacrifice may be necessary, that we shouldn't necessarily be seeking to suffer and making martyrs of ourselves, but that there is a certain openness and receptivity to those opportunities where there might be something to suffer for, that an individual may be uniquely prepared to engage in or find that, "Okay, this is actually my fight and this is where I demonstrate to the best of my ability my faith, that my belief in something higher is or can assist me at this time and this is the proof of it.

So I wonder if you might flesh that out a little bit Rod.

Rod: Well when you say that it reminds me of sitting with Father Kirill Kaleda at his rectory in Russia at the Butovo Field. Butovo Field is a place south of Moscow on the farthest southern outreaches of Moscow where, in the 1930s in a 14 month period the KGB executed 21,000 political prisoners on this field. Today, thanks largely to the work of this tireless Orthodox priest, Father Kirill Kaleda, that space has been consecrated as Russia's national monument to victims of political violence.

I went there to visit it on the Day of Remembrance and I watched a large group of Russians standing there in the cold rain reading out aloud the names of each victim who was killed there. After it was over I went to talk to Father Kirill to interview him for the book and one thing he told me is that we must always be ready to suffer if that is asked of us. But as you point out, we shouldn't seek it out. Our faith doesn't require us to seek it out and one has to really use prudential judgment. You can't die on every single hill. There may be times when you have to keep your mouth shut or walk on by something that offends you because there's a greater battle to be fought.

The difficulty though is trying to know when this is a stand I have to take and when I can pass it by because if you start by saying, "Well I'm not going to stand up against this thing, I'm going to wait until the big thing comes along," you'll eventually talk yourself out of standing up at all. I talk in Live Not By Lies about this thing called ketman (inward dissent). Czesław Miłosz, the Polish dissident writes in his book The Captive Mind about a phenomenon he calls ketman. It's a Persian word meaning the official hypocrisy, the mask that everybody has to wear in a system where it's too dangerous to tell the truth and he says you get to a point though where if you wear that mask too often, the mask becomes your face. This is the real challenge and I don't think there's a clear formula that tells us what we have to do in every single situation. It requires judgment. It's the sort of thing that we can only really work out talking to people we respect who share our values and who don't want to see us suffer but who also know that suffering can be required of us.

Nowadays I hear from people all the time who say that they try to talk to their pastors about the things they're struggling with in the workplace with whether or not they should stand up and be counted or if they stand up in this or that way and the pastors don't even know what they're talking about because the pastors have been so accustomed to thinking of Christianity as kind of a self-help therapeutic philosophy.

I'm sort of getting far afield from your question there but I think that it really does become an issue and that people like me - my job is independent. I work for a magazine. They're happy to have me. I can say what I want to, working for this conservative magazine. But when people write to me and tell me about their situations in their university or in their company, it feels a real challenge to me to weigh my words carefully because I'm not the one who's going to lose his career or who has to figure out how I'm going to feed my kids if I don't have my job.

But at the same time I want them to also be willing to honour their willingness to make the sacrifice if it's necessary, but without knowing them individually and knowing what their alternatives are and knowing what kind of support they would have, I can't just issue a blanket, "here's what you should do." But I think this is a good reason why we need to start talking about it right now, not just with our pastors but with our teachers and with people within the community so we can be training ourselves as Father Kolakovíc's students did to think what would we do if we were asked to make this sacrifice? Where is the line?

Elan: Very good.

Harrison: Great. I think we'll end it right there Rod.

Rod: Okay. I feel like we could go for another hour or so but actually I have things I have to do.

Harrison: Yeah, we could too. Maybe we could have you on again some time because I've still got a whole bunch of things I'd like to talk to you about. But if you could just stay on the line for a couple of minutes, we're going to sign off. I'll recommend the book again to all our listeners and viewers. Life Not By Lies.

Elan: Highly recommended.

Harrison: Highly recommended. Great book. And just want to say thanks again Rod for coming on and speaking to us. We had a great time and we hope everyone enjoyed it out there.

Rod: It's a great pleasure to be here. I'm just a journalist. I'm not an intellectual. I don't have the answers but I hope I've asked in this book the right questions, the sort of questions that will prompt others who are more creative than I am, who have resources that I don't have, to collaborate on building a network of resistance and mutual support that will get all of us through whatever difficult times are ahead. So thanks for being part of it.

Harrison: Good. Thank you Rod.

Elan: Thank you.

Reader Comments

I'm responding to this soft Marxism with some Hard Resistance. And they try to take away my ability to travel they'll find some hard lead, in their head, as in real Dead. (Komodo harris is a hard marxist/socialist, even in her own words).

Time for me to purchase some new reading material.

'Soft Totalitarianism'

all my life. I was endowed with a form of government, based on 'enumerated powers'

I grew complacent while that was slowly siphoned away...

sott.net is now imploring me to accept tyranny. it seems to me like they are in my face even..

SHOUTING deal with it.

or, did I miss something, eh?

Garbage - Stupid Girl - YouTube

are you in the market for a gun? if so, I have a french one, it was ONLY dropped once.. I suspect sir, that thou art lives in a place where... heaven forbid, your women are not allowed to own a gun..

is there a reason that you do NOT want your own woman to have a concealed gun sir?

if so. where I live is probably not a good place for you. (our women will put you down before you ever get to me)

as an American, I am aware sir that the world hates who I became..

rebuttal?

Rammstein - Amerika (Official Video) - YouTube

Speaking of 'soft totalitarianism', I imagine that someone like Goebells would be very impressed with Trump's distortion of reality and manipulation of his base through his twitter account.

Sheena Easton - Strut - Official Music Video - YouTube

As Rod Dreher puts it' "So the guy Trump pardoned, Gen. Flynn? He's now calling for martial law and a revote to get the result he prefers. I dunno, I'm starting to think our country hasn't been in the most trustworthy hands these past four years."

That is UNTIL November 4th 2020....poof like a fart in the wind. It’s as if the left, the media, the warnings, & the 24/7 fear porn narrative about illegitimacy and fraud went out the window. Now the refrain is WE HAVE THE MOST SOUND ELECTIONS IN THE WORLD, the MOST INTEGRITY AND ZERO FRAUD. If anyone of the 74 million people who voted for Trump points out the statistical anomalies, improbabilities, problems with Dominion (like NBC, CBS & CNN did for years) We are all conspiracy theorists, bigots and sore losers.

So, forgive me if I don’t immediately genuflect to the party that tells little boys they too can menstruate, that there are 77 genders, carbon an essential element to all life is killing the earth and Joe “you ain’t black” Biden got more black votes than Obama, in fact more votes than any president in US history. I’m not in favor of declaring martial law, I’d rather see it adjudicated in the courts but for once could we see perhaps an ounce of integrity on the left. Could we see Democrats care about what we perceive as our disenfranchisement?

Certainly, the Trump campaign should pursue their grievances through the courts. But if Trump cannot prove his claims in a court of law and still refuses to accept defeat, then his position would basically be impossible to disprove by any means. It would be unfalsifiable.

Such a position is totally unhinged from empirical reality.

When or if Trump is gone, you will show your true colours to those you are close to (or whatever constitutes 'closeness' for your ilk) and you will be treacherous. In time, you will betray your own family.

Just something to think about, or not.

I disagree because socialism relies on people caring more about people they do not know, love or care for, while capitalism acknowledges the basic human fact that people look out for #1 and or family and friends far more than they ever will for others.

Thus, socialism invites governmental virtue signalling, and government, by its nature, is wasteful enough, without adding PR bullshit to what few tasks it should be at least attempting to do.

I do agree with the fact that Globalism IS the problem, while there is nothing innately wrong with nationalism, despite what's been pitched by the BFM for over 100 years.

I do believe that the best description for the best government is 'that which governs least, governs best.' (I am aware that I'm mixing economic vs. political doctrines here - etc. but this will have to do.)

RC

garbade. but maybe with a shread of thruth in it 🤔

To JJJJ: 1) violates the self interest notions I've noted, which inevitably leads to serious economic, quality and other problems of a planned economy, et al.

2) " compulsory work " is typically found in socialist places, NOT libertarian / capitalist places. Indeed, it's anathema to libertarianism.

RC

Folks who believe that the world is filled with people who 'love thy neighbor before thyself' are not dealing with reality and governments that proclaim that they should be operating under such and illusion are even worse.

You state you can't believe you're posting a link to a video which extols the virtues of the DOI & US Constitution. Maybe you're saying that the guy was being too subservient to the "USA Saved The World" narrative, which clearly has outlived any usefulness or appropriateness.

I am thus at a loss - it seems that you're saying that we are disagreeing about something and I don't know what it is.

RC

It damn sure seems that you are expecting me to read you mind. Sorry; can't do.

R.C.

The discussion reminded me of Life and Fate by Vassily Grossman [Link]

Part I of Russian series on Amazon Prime [Link]

policeforfreedom valencia.. 29-11-2020 [Link]

Gotta say, we ALL have to get out of the habit of calling those sorry SOB's 'elites'; if they're 'elite' at anything, it's being evil.

R.C.

but, on the bright side, the laws of basic thermodynamics are for the better part still agreed upon, i think. 👍

RC

RC

I can probably slide this forum...

would you care to illuminate what was helpful. or a "good job" sir?

relatively soft individualism; [Link]

You need to learn :

1)- If you are 'replying' to someone's comment, go to the bottom right corner of that comment and click/pick the back/left turning arrow. It will then automatically place the name of your intended respondent in grey highlights, as it is for me now.

N.B., then, (hopefully, mostly, usually) the person to whom your reply is directed will, their next time here, see their 'Pavlovian Red Bell' alert which will say "HVAC Tech replied to you at Mind Matters Interview. . . etc."

2) It seems that you have intended to 'reply' to some folks above, but you failed to name them, and/or failed to 'click the blue bottom right back turning arrow icon.

3)- When you enter an internet address (e.g., www, http etc.) SOTT automatically hyperlinks the address. (If it's a SOTT article, it also does what it will do right now when I copy and paste from the address above, this article we are chatting under:

SOTT Focus:MindMatters: Interview with Rod Dreher: How to Survive the Coming Soft Totalitarianism

In 1974 world-renowned author of The Gulag Archipelago Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote a short essay to his Soviet compatriots beseeching them to live in truth. The message, called "Live Not By Lies"...For some reason, your links have not been coming through. What I do is open whatever I wish to link in a separate tab, copy that address, and paste it.

4) Finally, SOTT nowadays has an 'edit' function!

As my I.T. guy taught me long ago, 'when in doubt, right click.'

RC

Also:

4) Finally, SOTT nowadays has an 'edit' function! Right after you post a comment, it will appear as a pencil with eraser icon in the bottom right; click it to edit.

(Such as now. I already posted the above - you might have even read it! - but now, 1 minute later, I am adding this! I love it! )

Second addition via edit button/ icon: You did NOT hit the 'reply' icon in your 'thank you' comment. Again, right over here-->>>

RC

and the link goes to a foreign language website.

Helpful. Good job. RC.

well. i simply think that totalitarianism is the default mindset of humans. the only relevant alternative is individualism. meaning; if you dont like totalitarianism, start facing the totalitarianist within.

Goebbels would be far more impressed by the manipulative abilities of the mainstream media and the intelligence community than anything Trump has done.RC

RC

is it REALLY possible to 'pump heat' sir?

I PUT CURSOR on YOUR comment (ending: "is it REALLY possible to 'pump heat' sir? " )

In bottom right corner, I CLICKED that Blue back turning arrow.

Then, your name popped up (and will be above to the left.) Please try. DOWN and to the right (NOT the 'quote' indicator, the one to the left of that.) CLICK IT AND TYPE A REPLY, HIT ENTER!

RC

Good job! You've got it!

That phrase, 'heat pump' likewise always bugged me; seemed like some 99.99 % efficient transfer system.

RC

any idea? wise guy?

Energy transference: that we taketh, a little be giveth back... tis the proper Law of all things.

transpiration, perspiration. distillation = exasperation.. (for me anyhow..)

Imagine sir, that we mere humans were burning whale oil well into the 1850's for our light. (we were also riding animals to get around)

and then some guy put rock oil.. (petroleum) into a still... and out popped Kerosene.

why would any sane man do such a thing to a still? eh?

Steve Earle - Copperhead Road (Official Video) - YouTube

Here is your (intended?) hyperlink:

[Link]

RC

Speaking of copper line, have you ever heard James Taylor's Copperline? [Link] (Listening to it, and hearing my thumbing the A then E strings. (A major 4th drop? )

RC

or, you do not know what a still is. is it possible to Distill something..

without a still sir?

Distillation has to do with evaporation and condensation.

t.A.T.u. - All The Things She Said (Official Music Video) - YouTube

R.C.

BTW:

I think that you might be copying and pasting the TITLE rather than the ADDRESS of what you intend to link. Here is your most likely intended link: [Link]

(As re the music? Well, I guess that we've come across one that ain't my cup of tea, although I wouldn't throw her, nor her GF bimbo, out of bed, you understand. )

RC

Asphalt, is the stuff left over in the bottom of the tank. and what you drive on everyday.

and yes! I love you too Honey!

Vince Vance & The Valiants - All I Want for Christmas Is You - YouTube

Aerosmith - Pink (Official HD Video) - YouTube

RC

but not others.

[Link]

The Smithereens - Blood And Roses - YouTube

Technology is used to enslaved humanity more than it frees us (twas always short-lived promises with each new wonderous step 'forward')... And now, we are seeing the satanic fruits come to fruition before our very eyes.

Sometimes I think nedlud is right on the money.

I have now come to learn sir,.. that it was YOU who put me up to it.. I did, and now you accuse of a Demon?

MeThinks, thou art NOT my 'Anam-Chara'. .

my oh my, where is my Joyly or Lindamay when I NEED them so?

Tom Cochrane - Life Is A Highway (Official Video) - YouTube

Heat is a form of energy and CANNOT be pumped at will sir.

your turn...

unless you burn something, of course..

Collective Soul - December (Official Video) - YouTube

the reason that we insulate pipes, is to stop heat loss (or gain) until it gets to where it is needed.

does heat 'transfer' before that point. yes.

[Link]

if we can agree that heat can be electromagnetic radiation and/or movement of particles; then it can be claimed that nor electromagnetical radiation or movement of particles can be "pumped". (depending on how one defines a "pump" and "pumping").