The declaration that Donald Trump's onetime campaign manager employed a Russian intelligence officer was the headline-grabbing finding of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's fifth and final Russian interference report, released Aug. 18 at the time of the Democratic National Convention.

According to the report, Paul Manafort's 2016 interactions with his longtime associate, Ukraine-born Russian national Konstantin Kilimnik, "represent the single most direct tie between senior Trump Campaign officials and the Russian intelligence services," and amounted to "a grave counterintelligence threat" to the United States.

To hear Trump-Russia conspiracy advocates tell it, Kilimnik was the elusive missing link that proved the Trump campaign's complicity in Russian electoral interference. "Manafort, while he was chairman of the Trump campaign, was secretly communicating with a Russian intelligence officer with whom he discussed campaign strategy and repeatedly shared internal campaign polling data," five of the committee's Democratic members wrote in a pointed addendum. "This is what collusion looks like."

Comment: If you're grandfather looks like Winston Churchill, that doesn't make him Winston Churchill.

But the plain text of the Senate report contains no concrete evidence to support its conclusions. Instead, with a heavy dose of caveats and innuendo, reminiscent of much of the torrent of investigative verbiage in the Russiagate affair, the report goes to great lengths to cast a pall of suspicion around Kilimnik, much of which is either unsupported or contradicted by publicly available information.

The office of Democrat Mark Warner, the highest-ranking Senator on the committee through the duration of the probe until the report's release, did not respond to emailed questions about the panel's work.

Kilimnik: 'Likely' Channel to Russia?

For the record, Kilimnik has steadfastly denied that he is a Russian intelligence officer or has ties to Russian intelligence. Much of the Senate's portrayal of him relies on information gathered by special counsel Robert Mueller's team, which prosecuted Manafort on financial and lobbying charges stemming from his work in Ukraine prior to the 2016 campaign. Kilimnik, a 50-year-old political consultant, was born in Soviet Union-era Ukraine, attended a Soviet military academy, and maintains homes in both Ukraine and Russia. Starting in 2005, Kilimnik played a central role in Manafort's political operation in Ukraine, representing powerful oligarchs and helping guide Viktor Yanukovych to the presidency.

The Senate committee's claim that Kilimnik is a Russian spy goes far beyond the Mueller report, which stated that the FBI believes Kilimnik has unspecified "ties to Russian intelligence." (A similarly vague formulation was used about the reported spark for the FBI's Trump-Russia probe, Maltese professor Joseph Mifsud, whom the Mueller report described as having "connections to Russia.") The SSCI offers no window into how it went further than the Mueller report for its "assessment." Multiple sections purporting to contain supporting information are redacted. The Senate report also tacitly concedes it has no hard proof that Kilimnik shared information from Manafort with anyone, let alone officials in the Russian government. Kilimnik, it speculates, "likely served as a channel to Manafort for Russian intelligence services," an acknowledgment that it has not uncovered definitive proof.

A critical disclosure by the Mueller team during its investigation - but unmentioned in both the final Mueller and Senate reports - directly contradicts the Senate's assessment. After Mueller accused Kilimnik of having unspecified Russian intelligence "ties" in 2017, Manafort's legal team made multiple discovery requests for any communication between Manafort and "Russian intelligence officials." In April 2018, Manafort's attorneys revealed that the special counsel replied that "there are no materials responsive to [those] requests." The Mueller team's response marked a tacit admission that as of 2019, the FBI did not consider Kilimnik a Russian agent.

In recently unsealed notes from the FBI's collusion probe, Peter Strzok - the top FBI counterintelligence agent who opened the investigation - wrote in early 2017: "We are unaware of ANY Trump advisers engaging in conversations with Russian intelligence officials."

Asked by RealClearInvestigations if the FBI's assessment of Kilimnik has changed, a Department of Justice spokesman said that "the Mueller report speaks for itself," suggesting that it has not adopted the Senate committee's determination.

The unredacted sections of the Senate report that attempt to show that Kilimnik is a Russian spy rely on an assortment of emails, discussions, and even Twitter posts. The first visible (but still partially redacted) passage attempts to make an issue out of Kilimnik's discussions with his business partner, Sam Patten, about the nature of Russian intelligence work. Kilimnik, the report notes, trained in languages at a Soviet military school that he "himself admitted to colleagues was used by both the GRU and KGB." The SSCI then accuses Kilimnik of misleading Patten - in emails and perhaps some conversations - about "the type of career these intelligence officers followed compared to his own," and in claiming "that his former classmates were not involved in intelligence matters."

The next section reports that "in 2017, Kilimnik denied in private communications with Patten that there was Russian interference in the U.S. elections." The evidence to support that assertion is that "Kilimnik emailed Patten a Financial Times article on Russian interference in the U.S. elections," and joked that U.S. intelligence "must be having very little sleep chasing those squirrels who they think exist."

Beyond those emails, which prove nothing at all, the Senate report delves extensively into the activity of a Twitter account that it alleges Kilimnik used under the pseudonym "Petro Baranenko" (@PBaranenko). The account's tweets, SSCI says, "centered on efforts to discredit the Russia investigations." The report discloses the email address used to create the Twitter account but does not explain why it believes that Kilimnik is behind it. In a direct message exchange with RealClearInvestigations, the @PBaranenko account user denied being Kilimnik. "I am not Kilimnik and have nothing to do with him," the user wrote. "I have no idea why whoever wrote this report made this allegation."

The account user declined requests for an interview to corroborate that denial. Regardless, even if the account does belong to Kilimnik, the SSCI leaves unexplained how these innocuous emails and tweets amount to evidence that he is a Russian spy.

A 'Valuable Resource' for the U.S.

A deep and unresolved tension in the Senate report is that even as it declares that Kilimnik was a Russian intelligence officer, it documents his extensive U.S. government ties and involvement in political efforts hostile to Russian interests.

From 1995 to 2005, Kilimnik held a senior role at the Moscow office of the International Republican Institute, a U.S.-government organization that pursues American foreign policy objectives abroad. After leaving the IRI to work for Manafort's lobbying firm in Ukraine, Kilimnik, the report notes, became a "valuable resource" for officials at the U.S. Embassy in Kiev, with whom he was "in regular contact."

Kilimnik was tapped to "arrange meetings between Department of State officials and senior Ukrainian politicians." He served as "the primary point of contact" for multiple U.S.-Ukrainian talks. This included arranging a call between President Yanukovych and Vice President Joe Biden in November 2013. Kilimnik had "close proximity to" two key officials running U.S. policy in Ukraine, Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Victoria Nuland and U.S. Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt. Kilimnik, according to the Senate panel, attended multiple meetings with both officials and even served as a translator for at least one session with Nuland.

Kilimnik's contacts with U.S. officials extended beyond Kiev to Washington, D.C. During a trip to the U.S. in May 2016, the report notes, he met with a number of State Department officials, including Jonathan Finer, the chief of staff to then-Secretary of State John Kerry.

While the Senate report casts Kilimnik's proximity to the Trump campaign during the few months of Manafort's tenure in 2016 as a "grave counterintelligence threat" from Russia, it does not raise any alarm about Kilimnik's longer and deeper involvement with the highest reaches of the Obama U.S. State Department. The SSCI justifies this lack of concern by claiming that "most" State Department officials "were appropriately skeptical" of him. These officials, the report adds, were "occasionally dismissive of his reporting, and sometimes noted the need for caution when dealing with Kilimnik."

The report also ignores evidence that U.S. personnel shared intelligence with Kilimnik.

FBI and State documents not mentioned in the Senate report, first revealed by investigative journalist John Solomon in 2019, show that U.S. officials described Kilimnik as a "sensitive source" and exchanged inside information with him. In May 2016, the then-U.S. Ambassador to Zambia, Eric Schultz, who knew Kilimnik from a prior stint at the U.S. Embassy in Kiev, shared his personal assessments of then-incoming Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch and her deputy, George Kent.

The previous December, a U.S. Embassy official in Kiev, Alexander "Sasha" Kasanof, told Kilimnik about the Obama administration's assessment of a meeting between Yuriy Boyko, an associate of Ukrainian oligarch Dmitry Firtash, and Assistant Secretary of State Nuland. "I thought Boyko did quite well, in fact," Kasanof wrote. "Don't know that he convinced Nuland on everything (incl. [Firtash's] intentions), but his performance was much less Soviet and better than I thought would be."

'The U.S. Should Not Risk Losing Ukraine to Russia'

In contrast to the emails or tweets that it claims show Kilimnik's promotion of "pro-Russia narratives," the Senate report ignores the voluminous documentation, released by the Mueller team, detailing Kilimnik's involvement in a project directly counter to Russian interests. In the years before Yanukovych's ouster in February 2014, Manafort led a lobbying campaign for a Ukrainian-European Union economic agreement explicitly aimed at pushing Ukraine away from Russia and into the Western orbit.

Manafort's goal, he explained in several memos to Kilimnik and other colleagues, was to "[encourage] EU integration with Ukraine" so that Kiev does not "fall to Russia." Manafort sought to promote "constant actions taken by the Govt of Ukraine to comply with Western demands" and "the changes made to comply with the EU Association Agreement - which Russia staunchly opposed.

If Kilimnik were a Russian intelligence officer, his key role in an influence campaign to move Ukraine away from Russia would have been the perfect opportunity to engage in sabotage. But there is no evidence of this. Instead, Kilimnik played an integral role in Manafort's lobbying efforts across Europe. In short, during the same period that the SSCI posits that Kilimnik was acting as an intelligence officer on Russia's behalf, he was deeply involved in Manafort's efforts to advance the U.S. government's agenda in Ukraine.

'Opportunities' for Innuendo

While it ignores these countervailing facts about Kilimnik, the Senate report devotes dozens of pages to revisiting the controversy surrounding Kilimnik's alleged receipt of Trump campaign polling data from Manafort in 2016.

The Mueller report ultimately concluded that it "did not identify evidence of a connection between Manafort's sharing polling data and Russia's interference in the election," and, moreover, "did not establish that Manafort otherwise coordinated with the Russian government on its election-interference efforts."

The SSCI report offers nothing new to change the picture, beyond its own speculation. It has never been established that Kilimnik ever sent the data to anyone, and if he did, the only known alleged recipients were Ukrainians, not Russians. The report notes that it was "unable to obtain direct evidence of what Kilimnik did with the polling data and whether that data was shared further."

Rather than viewing the polling data incident as a "grave" act of Russian intelligence infiltration, the Senate report, like the Mueller report before it, contains a much simpler - and substantiated - explanation: Manafort shared the data to bolster his business interest. The Senate report notes that Manafort associate Rick Gates testified that he thought Manafort instructed him to share the polling data with Kilimnik "as part of an effort to resolve past business disputes and obtain new work with their past Russian and Ukrainian clients by showcasing Manafort's success," and to display "the strength of Manafort's position on the Campaign."

The report also recounts that in the immediate aftermath of his hiring as Trump campaign chair, Manafort reached out to three Ukrainian oligarchs and Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska in a bid to showcase his new position and float the possibility of future partnerships. Just two weeks after his hiring, Manafort wrote an email in which he "asked Kilimnik how his role with the Trump Campaign could be leveraged to collect the money owed to him by the OB [Opposition Bloc, a Ukrainian political party]." Gates, a key source for the SSCI's examination of Manafort, also testified that Manafort had told him that "working for the Trump Campaign would be 'good for business' and a potential way for Manafort's firm to be paid for work done in Ukraine for which they were owed."

It is also unclear how, even if it somehow ended up in the Kremlin's hands, this polling data could have been of use to an alleged Russian interference operation. As previous Senate reports have found, most of the ads and posts from the Internet Research Agency, the Russian troll farm indicted by Mueller, "were minimally about the candidates," were written in broken English, mostly ran after the election, and barely reached the battleground states. According to the former SSCI chair Richard Burr, Russian ad spending amounted to $1,979 in Wisconsin - all but $54 of that during the primary - $823 in Michigan, and $300 in Pennsylvania. In addition, as the Mueller team acknowledged in court, it did not possess "any evidence of substantive connections between the [IRA] and the Russian government."

The Senate report employs more qualified language for another explosive supposition, claiming to have "obtained some information suggesting Kilimnik may have been connected" to Russia's alleged hacking and leaking of Democratic Party emails in 2016. All the information that supposedly backs up this speculation is redacted. Meanwhile, the report acknowledges it "has no records of, and extremely limited insight into, Kilimnik's communications."

Because Kilimnik worked for Manafort, the Senate report concludes that Manafort's brief stint as Trump campaign chair "created opportunities for Russian intelligence services to exert influence over, and acquire confidential information on, the Trump Campaign." But the report does not contain a shred of evidence that any such "opportunities" were realized.

In the absence of concrete evidence, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's reliance on speculation and innuendo shows that it took ample opportunities to paint Kilimnik in a sinister light. That methodology applies to, and undermines, a number of other critical elements of the Senate committee's investigation, discussed in the second part of this special report.

Part 2: Senate Russiagate Report Left Big Stones Unturned. Two Were Named Mifsud and Assange.

The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's fifth and final Russia report has been widely greeted as a vindication of the Russia intrigue that has gripped the nation since 2016. Democratic Sen. Mark Warner says the report cataloged "a breathtaking level of contacts between Trump officials and Russian government operatives that is a very real counterintelligence threat to our elections."

The SSCI report, however, fails to show any coordinated activity between Trump, his campaign, and Russia. A companion article by RealClearInvestigations, for example, reports that its bombshell allegation - that former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort worked closely and shared information with a Russian intelligence officer - is based on innuendo rather than hard evidence.

A close reading of the report shows other instances where broad claims are made based on innocuous facts or heavily redacted material, making independent verification impossible. As was the case with the report issued by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, the Senate document minimizes or entirely omits countervailing information that calls into question its explosive suppositions, while including testimony that does not hold up to scrutiny. The Senate report also failed to document key facts because the committee did not interview important witnesses.

The report has been widely described as bipartisan, but it was not unanimous. Jim Risch (R-Idaho), the lone senator to vote against the committee's findings, claims the report relies heavily on speculation, not evidence. "Yes, I disagree with the report's 'assessment,' as there was no factual substantiation of it," Risch said in a statement. "The report assumes much."

A spokesperson for Risch declined further comment. Warner's office did not respond to emailed questions about the panel's work.

The Missing Mifsud 302

The FBI maintains that the years-long Trump-Russia probe was triggered by a single barroom conservation. Over drinks in London in May 2016, a low-level Trump campaign adviser named George Papadopoulos reportedly told an Australian diplomat that he had been tipped off that Russia had dirt on Hillary Clinton. Papadopoulos later told the FBI that the information came from a Maltese academic named Joseph Mifsud.

The Senate report, however, casts doubt on this origin story, only going so far as to say Papadopoulos "likely learned about the Russian active measures campaign as early as April 2016 from Joseph Mifsud." (emphasis added.) Nearly 500 pages later, contradicting itself, the report drops the qualifier: "The Committee found Mifsud was aware of an aspect of Russia's active measures campaign in the 2016 election and that Mifsud told Papadopoulos what he knew."

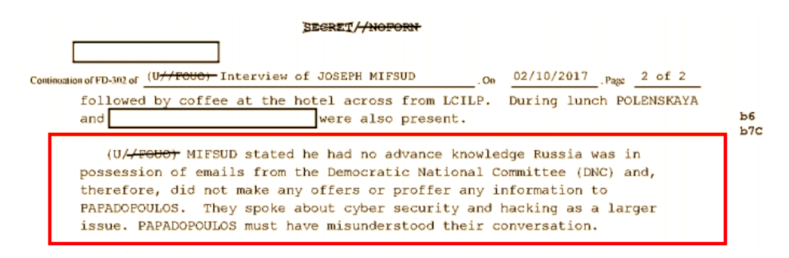

Mifsud's U.S. government ties even brought him to Washington in February 2017, where he spoke at a State Department-sponsored conference. Despite Mifsud's allegedly central role in its investigation, the FBI held just one known interview with him, in a D.C. hotel lobby. While the Senate report quotes extensively from the FBI's interview summaries (known as 302s) of multiple Mueller witnesses, including Papadopoulos, it contains no visible reference to the FBI's 302 on Mifsud (other references may be redacted).

Mifsud's FBI 302, however, was publicly disclosed just days after the Senate report's release.

The Senate report gives no indication that it sought to answer the many unanswered questions regarding Mifsud's identity and actions.

Assange: Another Missed Opportunity

The Senate report reveals a similar lack of investigative zeal regarding the other key episode that launched Russiagate: WikiLeaks' release of stolen Democratic Party emails.

According to the FBI, Alexander Downer, the Australian diplomat whom Papadopoulos supposedly spoke to in London, thought nothing of the conversation until weeks later in July 2016, when Julian Assange and WikiLeaks published the first tranche of stolen emails. Downer suspected that Russia was using the website to publish the dirt Papadopoulos had mentioned.

The Senate committee states in its report simply that it "requested but did not obtain an interview with Julian Assange," the WikiLeaks founder now fighting extradition from Britain to the U.S. A source close to WikiLeaks told RealClearInvestigations that Assange's U.S. legal team agreed to an interview but that the Senate committee never followed-up on his response. Attorney Adam Waldman, who had served as an intermediary between Assange and the U.S. government, has claimed that the committee's ranking Democrat, Warner, told him to cut off talks with Assange in April 2017. According to Waldman, Warner was acting at the behest of then-FBI Director James Comey, who reportedly told the Virginia senator to "stand down." Comey has never commented on the incident.

The Senate report once again relies on speculative language, contending that WikiLeaks "likely knew it was assisting a Russian intelligence influence effort" when it obtained and released Democratic Party emails during the 2016 campaign. It is unclear how the committee arrived at this conclusion. What is clear is that, just like the Mueller team before it, the committee passed up an opportunity to seek answers from the WikiLeaks publisher himself.

Different Standards on Deripaska

Waldman's contacts with Sen. Warner extended beyond the issue of Assange. They reveal more of the Senate report's missed opportunities with key witnesses.

Waldman also spoke to Warner about securing the testimony of his client Oleg Deripaska, the Russian oligarch best known for his association with Paul Manafort. In 2017, after Deripaska's name surfaced in media reports that tied him and Manafort to potential collusion, the aluminum tycoon took out newspapers ads offering to testify before Congress. The Senate panel does not explain why it did not take up Deripaska's offer. Waldman has claimed that the committee lost interest after he relayed that his client would not testify about collusion because "he doesn't know anything about that theory and actually doesn't believe it occurred." Waldman also accused members of the Senate of masking their disinterest by leaking false claims that Deripaska had demanded immunity as a condition of appearance. "Clearly, they did not want him to testify," Waldman said.

The Committee's approach to Deripaska also reveals more inconsistencies in how it scrutinizes Russian connections. The committee accuses Deripaska of acting as "proxy" for the Kremlin and conducting "influence operations" on its behalf, and says that his associates' proximity to Manafort constituted a "grave counterintelligence threat."

Yet the committee adopts a very different tone when it comes to Deripaska's other U.S. connections - most notably to the FBI and the Russia investigation. In 2009, when Robert Mueller headed the FBI, Deripaska funded a secret effort to rescue a captured CIA operative, Robert Levinson, in Iran. The Senate report mentions this in passing, and reduces it to "Deripaska's alleged cooperation with the FBI." But the cooperation was so substantial that the FBI repaid the favor by securing a U.S. visa for Deripaska - a fact unmentioned in the report. Also omitted is the fact that the FBI even tried to recruit Deripaska as an informant starting in 2014. The effort was abandoned two years later after the Russian tycoon informed agents that he had nothing to offer on Trump-Russia collusion, a theory he found "preposterous."

While Deripaska did not become an FBI source, he employed a key figure who did. The committee states that it found "multiple links" between Deripaska and Christopher Steele, the former British spy whose discredited Trump-Russia dossier was used for FBI surveillance applications and investigative leads. The report found that Steele worked for Deripaska from at least 2012 to 2017, including for an attempt to recover money from Paul Manafort.

The report also quietly mentions that several people behind the dissemination of the Steele dossier have Deripaska ties. In a footnote, the committee recounts testimony from former John McCain aide David Kramer that Glenn Simpson -- co-founder of Fusion GPS, the DNC contractor that hired Steele -- worked for Deripaska. Simpson downplayed this connection, a "discrepancy" that the committee says it did not resolve. (Kramer, was also a key figure in publicizing the dossier, leaking it to Buzzfeed and other media outlets). Simpson also refused to answer the Senate panel's additional questions about Steele's work for Deripaska. Also relegated to a footnote is the fact that Jonathan Winer, a State Department official who also used his position to spread the Steele dossier, acknowledged that he is a former Deripaska employee as well.

Comment: Winer is also one of disgraced criminal and inveterate liar Bill Browder's lawyers. If there's one thing all this gallery of rogues has in common, it is their anti-Russian sentiment.

The committee acknowledges that the Deripaska-Steele connection may have provided a "direct channel for Russian influence" on the dossier, and accordingly the FBI investigation that used it. Yet despite this risk, the committee does not conclude that Deripaska's proximity to the dossier's author, not to mention several key individuals who disseminated it, amounts to a grave counterintelligence threat.

'Authentic, Non-Public Knowledge'

A key component of the Trump/Russia conspiracy theory was that the Trump campaign conspired with, or had privileged information about, WikiLeaks' email releases. Like the Mueller team before it, the Senate committee fans the flames of this explosive claim in the dozens of pages it devotes to the actions of the veteran GOP operative Roger Stone. In June and October 2016, the Senate report says, Stone "likely" shared "additional information about WikiLeaks directly with Trump," and the two "likely spoke about WikiLeaks."

But the Senate committee also acknowledges that it "could not reliably determine the extent of authentic, non-public knowledge about WikiLeaks that Stone obtained and shared with the Campaign."

That is because, as the Mueller investigation made clear, Stone never obtained any non-public knowledge about WikiLeaks. His two suspected intermediaries, Jerome Corsi and Randy Credico, had no actual contact with WikiLeaks, and accordingly had no information to share.

Nonetheless, the Senate report goes to great lengths to suggest that WikiLeaks' Oct. 7, 2016 release of emails stolen from Clinton's campaign manager, John Podesta, was coordinated with Stone and Corsi in order to blunt the impact of the so-called "Access Hollywood" tape in which Trump made extremely coarse comments about women.

While it pores over Corsi's statements and recounts in granular detail his communications with Stone, the Senate report ignores countervailing, open source information that undermines the innuendo. Stefania Maurizi, an Italian journalist who worked with WikiLeaks on the Podesta release, has recounted that the timing of the Podesta publication was decided the day before its release. Maurizi confirmed to RealClearInvestigations that she was not invited to testify.

'How's Things Going With Russia?'

The Senate report's section on former Trump lawyer Michael Cohen reveals a willingness to include false information that fuels the Russiagate narrative. A popular theory - advanced most recently by former FBI agent Peter Strzok -- contends that Trump is beholden to Russia financially, and thus subject to compromise. Chief among Trump's supposed financial entanglements with Moscow is his aborted effort to build a Trump Tower in Moscow. The Senate report repeatedly cites this project but never reveals anything beyond what was already known: The effort was entirely prospective, and never advanced beyond a non-binding letter of intent as well as -- in Cohen's angry words to a colleague -- "a bullshit garbage invite" to Russia "by some no name clerk at a third-tier bank." As Cohen told MSNBC earlier this month: "There was never discussion with anybody about the financing of this project. There was never a piece of property to put it on."

Nevertheless, the report includes Cohen's implausible testimony describing the campaign period up until June 2016, when the Trump Tower Moscow project was abandoned for good. Cohen told the committee:

In other words, Mr. Trump is out there on the rally, in the public, stating there's no Russian collusion, there's no involvement, there's no deals, there's no connection. And yet, the following day, as we're walking to his car, he's asking me, "How's things going with Russia?"It is certainly true that Trump did not disclose the Trump Tower Moscow project on the campaign trail. But the public record is clear that it would have been impossible for Trump to claim "no Russian collusion" in public while simultaneously asking about Trump Tower Moscow in private. Up until June 2016, Trump's dealings with Russia were barely a public issue, and "collusion" was not one at all. Collusion would only arise publicly many months later, after the 2016 election, making Cohen's account untenable. Cohen made similarly false statements to the House Intelligence Committee in early 2019. Yet, despite being indicted for false statements to Congress that the Mueller team claimed were aimed at protecting Trump, he has faced no scrutiny or charges for statements that fueled the narrative of Trump's illicit Russian ties.

New Questions for CrowdStrike

Instead of providing clarity, the Senate report creates new confusion regarding a central question: Did the Russians actually steal Democratic Party emails by hacking into the DNC servers? The FBI never directly examined the servers that housed the purloined emails. Jim Comey said he made "multiple requests" to the DNC for the servers but was rebuffed. It is not clear why he took no for answer.

As a result, the bureau - as well as Mueller and the Senate committee - relied heavily on a forensic analysis performed by a DNC contractor, CrowdStrike. The report recounts that during his interview with the committee, CrowdStrike President Shawn Henry said his firm had found evidence of Russian hacking. It states:

Henry testified that CrowdStrike was "able to see some exfiltration and the types of files that had been touched" but not the content of those files.Henry's claim that Crowdstrike was "able to see some exfiltration" is at odds with his testimony to the House Intelligence Committee in December 2017. As RealClearInvestigations has previously reported, Henry testified then that CrowdStrike "did not have concrete evidence" that Russian hackers exfiltrated data from the DNC servers. "There's circumstantial evidence, but no evidence that they were actually exfiltrated," he told the House panel. "There are times when we can see data exfiltrated, and we can say conclusively. But in this case, it appears it was set up to be exfiltrated, but we just don't have the evidence that says it actually left." Asked by RCI to explain the discrepancy, a CrowdStrike representative referred RealClearInvestigation to the firm's blog post in response to the release of his House testimony. "Shawn Henry stated in his testimony to the House Intelligence Committee that CrowdStrike had indicators of exfiltration and that data had clearly left the network," the post says.

The SSCI also draws heavily on CrowdStrike's analysis of the DNC server in reports that have never been publicly released. Justice Department officials have previously disclosed that CrowdStrike's reports were delivered in draft form, and redacted by DNC attorneys. Both CrowdStrike and the DNC claim to have fully cooperated with the FBI, but the Senate report tells a different story.

On Aug. 31, 2016, as the FBI's investigation of the DNC server breach was in full swing, CrowdStrike delivered a draft report that an unidentified FBI official described as "heavily redacted." James Trainor, then-assistant director of the FBI's Cyber Division, told the SSCI that he was "frustrated" with the CrowdStrike report and "doubted its completeness." Although the committee claims that the FBI ultimately obtained the data it sought, Trainor testified that the DNC's cooperation was "moderate" overall and "slow and laborious in many respects." Trainor singled out the fact that Perkins Coie, the DNC law firm that hired CrowdStrike (as well as Fusion GPS, the firm behind the Steele dossier), "scrubbed" the CrowdStrike information before it was delivered to the FBI:

As Trainor told the Committee: "having that information [raw data about the computer intrusion] collected, fully viewed by an attorney, scrubbed, sent over to the FBI in a stripped-down version three weeks later is not optimal."From an investigatory point of view, it is also not optimal that the two core allegations at the heart of Russiagate - the alleged Russian theft of Democratic Party emails and the Trump campaign's potential collusion with the Kremlin - were generated by Democratic Party contractors, CrowdStrike and Fusion GPS. Yet despite criticizing the FBI for failing to properly vet Christopher Steele, the SSCI report does not take issue with the outsized role and partisan conflicts of these two private firms.

'The Power to Investigate'

Although the Senate report has been widely interpreted as a bipartisan endorsement of the Trump-Russia collusion theory, that picture is misleading. Six Republican members state unequivocally in an addendum that the investigation "found no evidence" that the Trump campaign "colluded with the Russian government" in 2016. In early 2019, as the investigation neared its end, a Democratic aide on the committee acknowledged to CNN that it had "not uncovered direct evidence of collusion."

The Senate committee itself has also had a direct role in the selective leaks that fueled the collusion narrative. In 2018, James Wolfe -- the SSCI's longtime director of security - was convicted of lying to the FBI about his contacts with journalists about classified information before the committee. Wolfe had a romantic relationship with one of those reporters, Ali Watkins, now at the New York Times, who wrote a story for BuzzFeed about Carter Page's contacts with alleged Russian spies.

In what is perhaps a nod to the fact that its final report is heavy on speculation and light on new evidence, the SSCI opens the nearly 1,000-page document with the disclaimer that it "does not describe the final result as a complete picture." In an addendum, five of the committee's Democratic members note that the panel's "power to investigate -- which does not include search warrants or wiretaps -- falls short of the FBI's. So too do its staffing, resources, and technical capabilities."

As a result, far from being treated as a breakthrough in the years-long Trump-Russia saga, the SSCI's main contribution to the available picture is its own creative interpretation of previously known information.

Its release comes while another major investigation with far greater investigative powers is believed to be near completion. The review by U.S. Attorney John Durham into the origins of the Russia probe recently yielded its first indictment. Whether more are forthcoming or not, the innuendo that fills the Senate intelligence panel's last word on the Russia investigation underscores that the full story has yet to be told.

These demented people have forgotten what evidence and proof look like, when their favourite word is ‘likely’.