WHAT DO YOU get when you add up a bunch of donuts? According to optical physicists: a croissant.

That's the result of new research revealing a never-before-seen property of light called self-torque. This newfound characteristic of photons involves a twisting laser beam that spins faster and harder, similar to a bit of dirt as it whirls down a drain. The odd behavior, described today in the journal Science, might one day lead to improved communications technology and novel ways of manipulating microscopic objects.

"We're always discovering new things in science, but it's not that often you discover a new fundamental property," says study coauthor Kevin Dorney, a physical chemist at the JILA laboratory run by the University of Colorado, Boulder, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Extreme optical baking

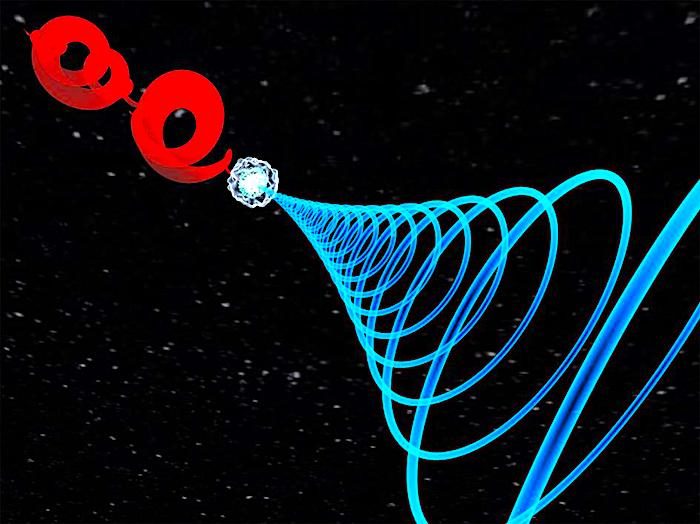

The recipe for pastry-shaped lasers starts with a type of light that possesses what's known as orbital angular momentum. This property, itself only officially discovered in 1992, can be imparted to a laser beam when it passes through a seashell-shaped lens. The light emerges looking like a helix corkscrewing around a central point. Shine the laser on a surface, and it will look like a fat ring with a hole in the center or, more colloquially, a donut.

A nano-size particle placed in its path will start to spin like a planet around a star-hence the property's astronomical moniker.

Dorney and his colleagues had been working on making light with orbital angular momentum in a region of the electromagnetic spectrum known as the extreme ultraviolet - situated between the well-known ultraviolet produced in black light lamps and the high-energy x-rays used in medical technology.

The extreme ultraviolet lasers had to be produced using two red optical laser pulses shot into a collection of gaseous argon atoms. The red laser light liberated electrons from the argon, which would then "ride the waves of the laser like a surfer and gain energy," Dorney says. When the newly energized electrons slammed back into the argon atoms, they released their excess energy as extreme ultraviolet photons with orbital angular momentum.

The team then wondered what would happen if their initial red laser pulses had different orbital angular momentum speeds and were out of sync with one another by a few quadrillionths of a second. Simulations showed that the donut-shaped optical pulses would add together in a strange way, causing the resulting helical extreme ultraviolet beams to quickly ratchet up their twisting. In these models, a cross-section of the ultraviolet laser looked like the waning moon or, in pastry terms, a croissant.

"You wouldn't expect from adding donuts that you would get a croissant," Dorney says. But sure enough, when the researchers tried the experiment with actual light, "we clicked the right button, and it went from a donut to a croissant and back again."

Bright future

The team is calling the newly discovered property of light self-torque, because it is akin to a wrench speeding up as it tightens a bolt, except in that case, the torque is being caused by an external agent - the hand accelerating the wrench. True self-torque is seen in very few systems in nature, and generally only in extreme situations. For instance, when two black holes revolve around one another, their gravitational interactions can cause them to yank on each other and rapidly speed up their spinning.

So what uses does light with self-torque have?

"The short answer is, we're still figuring that out," Dorney says. "The property is so new that the immediate applications are not obvious."

But the situation was much the same when light with orbital angular momentum was first produced more than a quarter century ago. Nowadays, it is being used to make ultra-powerful microscopes, move tiny parts of industrial machinery, and send extremely high data rate signals through optical communications networks. Perhaps that's why discovering another new property of light has made other researchers in this field giddy.

"It's just so exciting and fascinating," says Alan Willner, an electrical engineer at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the recent work. "It's like a gift that keeps giving."

Then using the cork screw analogy, could this interrupt the flow of information, this struck me from the article

The team is calling the newly discovered property of light self-torque, because it is akin to a wrench speeding up as it tightens a bolt, except in that case, the torque is being caused by an external agent - the hand accelerating the wrench. True self-torque is seen in very few systems in nature, and generally only in extreme situations. For instance, when two black holes revolve around one another, their gravitational interactions can cause them to yank on each other and rapidly speed up their spinning.

So what use does light with self-torque have?

"The short answer is, we're still figuring that out," Dorney says. "The property is so new that the immediate applications are not obvious."

So it makes me wonder, what are the external forces in play, that have the ability to torque light.

With recent discoveries regarding life in the world we live, engineers seem to be on the forefront of discoveries. I guess, it must be their burning passion for finding out "how things work".

Just my thought.