Talk about inhaling your food: The iconic predator Tyrannosaurus rex and its kin had some of the keenest senses of smell among all extinct dinosaurs, a new study finds. The work, published yesterday in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, attempts to roughly quantify how many genes would have been involved in T. rex's sniffing skills, tens of millions of years after any traces of its DNA have decayed away.

The idea that tyrannosaurs had good noses is not new. In 2008, for instance, researchers showed that T. rex and its siblings devoted large portions of their brains to processing smell. But the new study marks the latest in a growing movement to correlate living animals' DNA with their bodies and sensory abilities, with the goal of better understanding the capabilities and behaviors of their long-extinct relatives.

Dinosaurs 101 Over a thousand dinosaur species once roamed the Earth. Learn which ones were the largest and the smallest, what dinosaurs ate and how they behaved, as well as surprising facts about their extinction.

"I welcome this work-it seems that this is another contribution to the whole body of work, where people are using cues from genes and morphology to infer sensory function and ecological [roles in] extinct species," says Deborah Bird, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has used similar techniques to reconstruct the smelling repertoire of the extinct sabertooth cat Smilodon.

Sniffing out clues

Hughes and his colleague John Finarelli, a paleobiologist at University College Dublin, had long been enamored with the idea of looking at dinosaur senses-and focused their efforts on smell.

"What did the Cretaceous environment smell like? Everybody talks about about what it looks like-but what did it smell like?" says Hughes.

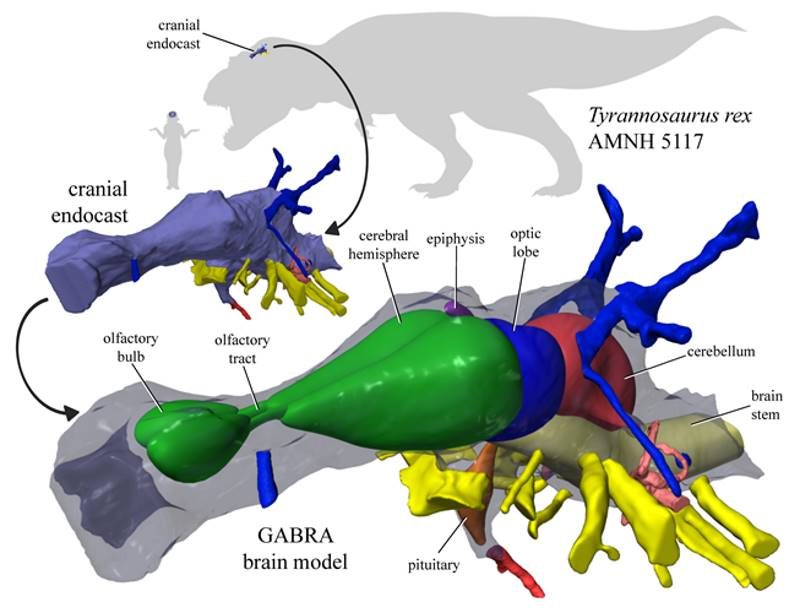

For this paper, the pair homed in on the overall shape of dinosaur brains, which can be partially preserved as impressions on the inner surfaces of some well-preserved skulls. It may sound like a tall order to suss out the details, but thankfully, the researchers had living references: birds, the last living dinosaurs.

Generally speaking, living birds with more olfactory receptors-proteins that bind with specific odor molecules-tend to have disproportionately large olfactory bulbs, the regions in their brains that process smells. So Hughes and Finarelli combed the scientific literature for records of olfactory bulb sizes and measured brain-size ratios for 42 living birds, two extinct birds, the American alligator, and 28 extinct non-avian dinosaurs. They also tracked down the DNA of many living birds, and then combined all that data with a previously published study to build a new database of the living animals' olfactory receptor genes.

When the researchers projected the resulting model of living creatures back to dinosaurs, they found that Tyrannosaurus rex probably had between 620 and 645 genes encoding its olfactory receptors, a gene count only slightly smaller than those in today's chickens and house cats. Other large meat-eating dinosaurs, such as Albertosaurus, also had large olfactory receptor gene counts.

But smell isn't just for finding food. Animals use odors to recognize their kin, mark their territories, attract mates, detect predators, and more. Among all living vertebrates, the record for the most olfactory receptor genes rests with the modern elephant, a plant-eater with about 2,500 such genes. With such an exquisite sense of smell, elephants can "count" quantities of food by odor alone.

Sure enough, some plant-eating dinosaurs showed evidence of a greater reliance on smell than some meat-eaters. One of the herbivores Hughes and Finarelli examined, the theropod Erlikosaurus, had more projected olfactory receptor genes than Velociraptor and many of that raptor's kin. Still, T. rex and Albertosaurus still had the best estimated smelling ability of all.

A whiff of the unknown

Future work may examine what, exactly, T. rex and its kin were sniffing during the age of dinosaurs. Existing data let Hughes and Finarelli infer certain odors in the dinosaur repertoire, such as blood and generic vegetation. But entire clusters of olfactory receptor genes haven't yet been traced back to particular smells.

"It's a very strange one, that we have so much information on how smell works, but so little information on what smell binds what odorant receptor," Hughes says. "Maybe there are some fragrance companies who have all this proprietary information, but in terms of the science, we just don't know-it's one of the grand challenges in science."

The researchers say that future studies could also track the trade-offs inherent in sensory evolution over time, such as the weakening of some aquatic mammals' sense of smell as their ancestors moved into the water. Hughes says that similar work could be done in nonavian dinosaurs-work that's captivated his imagination.

"I've loved dinosaurs since I was a kid," he says, "so it was really great to contribute something to the overall knowledge base of dinosaurs, even if it's small."

Michael Greshko is a writer for National Geographic's science desk, covering everything from dinosaurs to dark matter. He previously wrote for Inside Science News Service at the American Institute of Physics and has written for MIT Technology Review, NOVA Next, and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

... and then a comet hit, they all died and become fossil fuel .... fantasies