© The Intercept

I was sitting in the nearly empty restaurant of the Westin Hotel in Alexandria, Virginia, getting ready for a showdown with the federal government that I had been trying to avoid for more than seven years. The Obama administration was demanding that I reveal the confidential sources I had relied on for a chapter about a botched CIA operation in my 2006 book, "

State of War."

I had also written about the CIA operation for the New York Times, but the paper's editors had suppressed the story at the government's request. It wasn't the only time they had done so.A MARKETPLACE OF SECRETSBundled against the freezing wind, my lawyers and I were about to reach the courthouse door when two news photographers launched into a perp-walk shoot. As a reporter, I had witnessed this classic scene dozens of times, watching in bemusement from the sidelines while frenetic photographers and TV crews did their business. I never thought I would be the perp, facing those whirring cameras.

As I walked past the photographers into the courthouse that morning in January 2015, I saw a group of reporters, some of whom I knew personally. They were here to cover my case, and now they were waiting and watching me. I felt isolated and alone.

My lawyers and I took over a cramped conference room just outside the courtroom of U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema, where we waited for her to begin the pretrial hearing that would determine my fate. My lawyers had been working with me on this case for so many years that they now felt more like friends. We often engaged in gallows humor about what it was going to be like for me once I went to jail. But they had used all their skills to make sure that didn't happen and had even managed to keep me out of a courtroom and away from any questioning by federal prosecutors.

Until now.

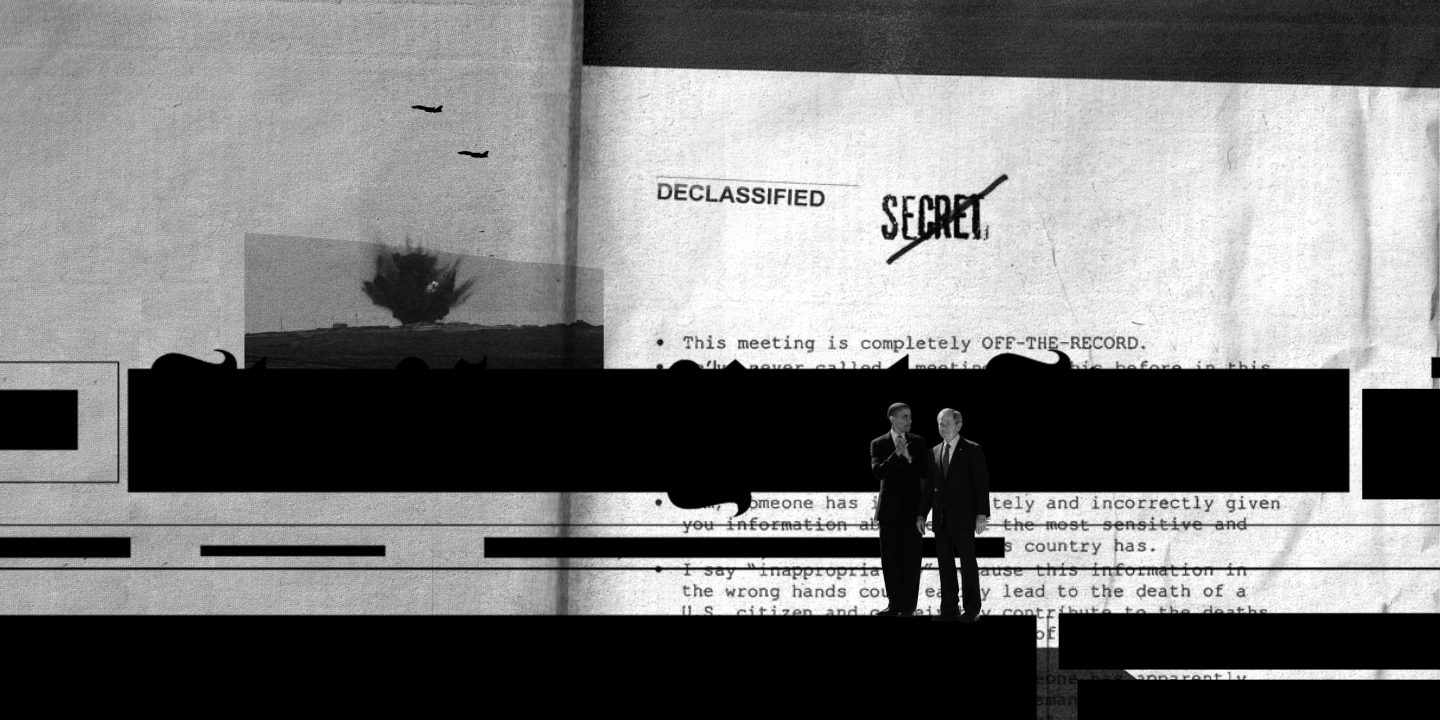

My case was part of a broader crackdown on reporters and whistleblowers that had begun during the presidency of George W. Bush and continued far more aggressively under the Obama administration, which had already prosecuted more leak cases than all previous administrations combined.

Obama officials seemed determined to use criminal leak investigations to limit reporting on national security. But the crackdown on leaks only applied to low-level dissenters; top officials caught up in leak investigations, like former CIA Director David Petraeus, were still treated with kid gloves.Initially, I had succeeded in the courts, surprising many legal experts. In the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Brinkema had sided with me when the government repeatedly subpoenaed me to testify before a grand jury. She had ruled in my favor again by quashing a trial subpoena in the case of Jeffrey Sterling, a former CIA officer who the government accused of being a source for the story about the ill-fated CIA operation. In her rulings, Brinkema determined that there was a "reporter's privilege" - at least a limited one - under the First Amendment that gave journalists the right to protect their sources, much as clients and patients can shield their private communications with lawyers and doctors.

But the Obama administration appealed her 2011 ruling quashing the trial subpoena, and in 2013, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, in a split decision, sided with the administration, ruling that there was no such thing as a reporter's privilege. In 2014, the Supreme Court refused to hear my appeal, allowing the 4th Circuit ruling to stand. Now there was nothing legally stopping the Justice Department from forcing me to either reveal my sources or be jailed for contempt of court.

But even as I was losing in the courts, I was gaining ground in the court of public opinion. My decision to go to the Supreme Court had captured the attention of the nation's political and media classes. Instead of ignoring the case, as they had for years, the national media now framed it as a major constitutional battle over press freedom.

That morning in Alexandria, my lawyers and I learned that the prosecutors were frustrated by my writing style. In "

State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration," I didn't include attribution for many passages. I didn't explicitly say where I was getting my information, and I didn't identify what information was classified and what wasn't. That had been a conscious decision; I didn't want to interrupt the narrative flow of the book with phrases explaining how I knew each fact, and I didn't want to explicitly say how I had obtained so much sensitive information. If prosecutors couldn't point to specific passages to prove I had relied on confidential sources who gave me classified information, their criminal case against Sterling might fall apart.

When I walked into the courtroom that morning, I thought the prosecutors might demand that I publicly identify specific passages in my book where I had relied on classified information and confidential sources. If I didn't comply, they could ask the judge to hold me in contempt and send me to jail.

I was worried, but I felt certain that the hearing would somehow complete the long, strange arc I had been living as a national security investigative reporter for the past 20 years. As I took the stand, I thought about how I had ended up here, how much press freedom had been lost, and how drastically the job of national security reporting had changed in the post-9/11 era.

THERE'S NO PRESS ROOM at CIA headquarters, like there is at the White House. The agency doesn't hand out press passes that let reporters walk the halls, the way they do at the Pentagon. It doesn't hold regular press briefings, as the State Department has under most administrations. The one advantage that reporters covering the CIA have is time. Compared to other major beats in Washington, the CIA generates relatively few daily stories. You have more time to dig, more time to meet people and develop sources.I started covering the CIA in 1995. The Cold War was over, the CIA was downsizing, and CIA officer Aldrich Ames had just been unmasked as a Russian spy. A whole generation of senior CIA officials was leaving Langley. Many wanted to talk.

I was the first reporter many of them had ever met. As they emerged from their insular lives at the CIA, they had little concept of what information would be considered newsworthy. So I decided to show more patience with sources than I ever had before. I had to learn to listen and let them talk about whatever interested them. They had fascinating stories to tell.

In addition to their experiences in spy operations, many had been involved in providing intelligence support at presidential summit meetings, treaty negotiations, and other official international conferences. I realized that these former CIA officers had been backstage at some of the most historic events over the last few decades and thus had a unique and hidden perspective on what had happened behind the scenes in American foreign policy. I began to think of these CIA officers like the title characters in Tom Stoppard's play "

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead," in which Stoppard reimagines "

Hamlet" from the viewpoint of two minor characters who fatalistically watch Shakespeare's play from the wings.

While covering the CIA for the

Los Angeles Times and later the

New York Times, I found that patiently listening to my sources paid off in unexpected ways.

During one interview, a source was droning on about a minor bureaucratic battle inside the CIA when he briefly referred to how then-President Bill Clinton had secretly given the green light to Iran to covertly ship arms to Bosnian Muslims during the Balkan wars. The man had already resumed talking about his bureaucratic turf war when I realized what he had just said and interrupted him, demanding that he go back to Iran. That led me to write

a series of stories that prompted the House of Representatives to create a special select committee to investigate the covert Iran-Bosnia arms pipeline.

Another source surprised me by volunteering a copy of the CIA's secret history of the agency's involvement in the 1953 coup in Iran. Up until then, the CIA had insisted that many of the agency's internal documents from the coup had long since been lost or destroyed.But one incident left me questioning whether I should continue as a national security reporter. In 2000, John Millis, a former CIA officer who had become staff director of the House Intelligence Committee, summoned me to his small office on Capitol Hill. After he closed the door, he took out a classified report by the CIA's inspector general and read it aloud, slowly, as I sat next to him. He repeated passages when I asked, allowing me to transcribe the report verbatim. The report concluded that top CIA officials had

impeded an internal investigation into evidence that former CIA Director John Deutch had mishandled large volumes of classified material, placing it on personal computers in his home.

The story was explosive, and it angered top CIA officials.

Several months later, Millis killed himself. His death shook me badly. I didn't believe that my story had played a role, but as I watched a crowd of current and former CIA officials stream into the church in suburban Virginia where his funeral was held, I wondered whether I was caught up in a game that was turning deadly. (I have never before disclosed that Millis was the source for the Deutch story, but his death more than 17 years ago makes me believe there is no longer any purpose to keeping his identity a secret. In an interview for this story, Millis's widow, Linda Millis, agreed that there was no reason to continue hiding his role as my source, adding: "I don't believe there is any evidence that [leaking the Deutch report] had anything to do with John's death.")

Another painful but important lesson came from

my coverage of the case of Wen Ho Lee, a Chinese-American scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, who in 1999 was suspected by the government of spying for China. After the government's espionage case against him collapsed, I was heavily criticized - including in

an editor's note in the

New York Times - for having written stories that lacked sufficient caveats about flaws and holes in the government's case. The editor's note said that we should "have pushed harder to uncover weaknesses in the FBI case against Dr. Lee," and that "in place of a tone of journalistic detachment from our sources, we occasionally used language that adopted the sense of alarm that was contained in official reports and was being voiced to us by investigators, members of Congress and administration officials with knowledge of the case."

In hindsight, I believe the criticism was valid.

That bitter experience almost led me to leave the

Times. Instead, I decided to stay. In the end, it made me much more skeptical of the government.

Success as a reporter on the CIA beat inevitably meant finding out government secrets, and that meant plunging headlong into the classified side of Washington, which had its own strange dynamics.

I discovered that there was, in effect, a marketplace of secrets in Washington, in which White House officials and other current and former bureaucrats, contractors, members of Congress, their staffers, and journalists all traded information. This informal black market helped keep the national security apparatus running smoothly, limiting nasty surprises for all involved. The revelation that this secretive subculture existed, and that it allowed a reporter to glimpse the government's dark side, was jarring. It felt a bit like being in the Matrix.

Once it became known that you were covering this shadowy world, sources would sometimes appear in mysterious ways. In one case, I received an anonymous phone call from someone with highly sensitive information who had read other stories I had written. The information from this new source was very detailed and valuable, but the person refused to reveal her identity and simply said she would call back. The source called back several days later with even more information, and after several calls, I was able to convince her to call at a regular time so I would be prepared to talk. For the next few months, she called once every week at the exact same time and always with new information. Because I didn't know who the source was, I had to be cautious with the information and never used any of it in stories unless I could corroborate it with other sources. But everything the source told me checked out. Then after a few months, she abruptly stopped calling. I never heard from her again, and I never learned her identity.

Disclosures of confidential information to the press were generally tolerated as facts of life in this secret subculture. The media acted as a safety valve, letting insiders vent by leaking. The smartest officials realized that leaks to the press often helped them, bringing fresh eyes to stale internal debates. And the fact that the press was there, waiting for leaks, lent some discipline to the system. A top CIA official once told me that his rule of thumb for whether a covert operation should be approved was, "How will this look on the front page of the

New York Times?" If it would look bad, don't do it. Of course, his rule of thumb was often ignored.

For decades, official Washington did next to nothing to stop leaks. The CIA or some other agency would feign outrage over the publication of a story it didn't like. Officials launched leak investigations but only went through the motions before abandoning each case. It was a charade that both government officials and reporters understood.

Read more...

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter