The inferred location of the blast was about halfway between South Africa and Antarctica. This may not seem like an important clue to post-Cold War babies; people forget that South Africa is known to have had the bomb throughout the 1980s. The apartheid regime built a half-dozen warheads for tactical use and regional deterrence against such Communist-influenced neighbour states as Angola. In 1989, during the run-up to South African democracy, the republic voluntarily dismantled its nukes. Over the next decade it joined the major nonproliferation treaties, and even led the creation of a new one, the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty.

The new research paper on the Vela Incident, published in the journal Science & Global Security last month, is not a sensational novelty. Mostly I am mentioning it because it may be nice, in 2018, to imagine a rogue member of the Nuclear Club one day leaving it and becoming a leading anti-nuke sentinel.

With all that said, South Africa is not necessarily the prime suspect in this whodunit. Vela 6911 was part of a global grid of satellites designed to help enforce the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, which outlawed nuclear testing in the atmosphere (and in space). The satellites' main instruments for spotting atmospheric nuke tests were arrays of light-detecting photodiodes called "bhangmeters" (whose name is a slightly complicated physicists' joke about cannabis. Yes, really).

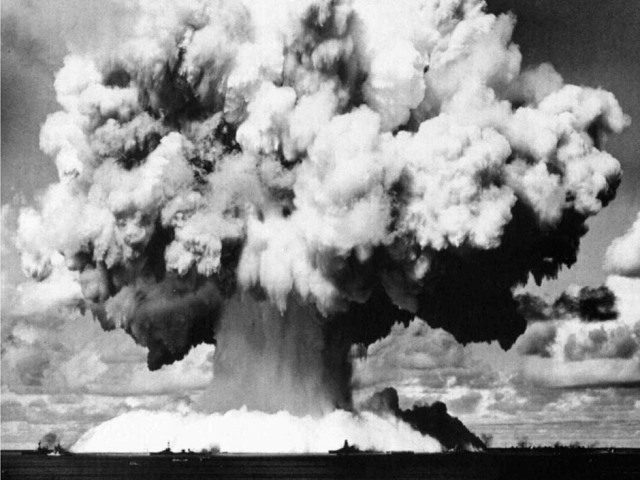

Nuclear explosions create an interesting double-humped or M-shaped signal on light detectors in the first second or so after they detonate. There's an initial, brief fireball "set off" by X-rays heating the air (and anything else that might be very nearby) to hundreds of thousands of degrees. Then the mechanical shock wave of the explosion, at first opaque, conceals the first fireball.

Cooling as it expands, the shock wave becomes translucent, and there is a "second maximum" of brightness. The resulting M-shaped curve is the same for fission and fusion weapons, can be used to calculate the total energy of the explosion, and is not known to be imitated by any other natural phenomenon.

The CIA studied the signal and decided that it was, in fact, the thumbprint of a low-yield nuke. President Jimmy Carter convened a blue-ribbon scientific panel to study the signal: it was led by Jack Ruina, an MIT electrical engineering prof who had once been director of the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. This is to say that Ruina had very strong science credentials, and equally impressive deep-state credentials. Ruina's panel issued what one member called a "Scotch verdict": it said it could not rule out a natural explanation for the signal.

The new paper by Christopher M. Wright and Lars-Erik de Geer pulls together the many shreds of public-domain knowledge about the physics of the Vela Incident. Some of them have come from material declassified piecemeal, and far from completely, over the intervening decades. The public has only been allowed to scrutinize selected items from a "zoo" of Vela false alarms cited by the Ruina panel as proof that the Incident might have been some kind of micrometeor phenomenon. Meanwhile, Vela readings from the last known atmospheric nuke tests have also been misplaced. As Wright and de Geer document, even this threadbare evidence does not leave much room to doubt that the incident was a nuke. The panel's alternate scenarios are pretty contrived, especially given what the human species has learned since about the statistics of very tiny particles that whiz about the cosmos and occasionally smash into satellites.

Wright and de Geer do not dig into the historical literature of Vela, which has been expanding persistently as intelligence-world memoirs and diaries are published or declassified. Even president Carter wrote, not long after his panel had completed its preliminary work, of "a growing belief among our scientists that the Israelis did indeed conduct a nuclear test explosion in the ocean near the southern end of South Africa."

Comment:

The truth about Israel's secret nuclear arsenal

A few years later, on 22 September 1979, a US satellite, Vela 6911, detected the double-flash typical of a nuclear weapon test off the coast of South Africa. Leonard Weiss, a mathematician and an expert on nuclear proliferation, was working as a Senate advisor at the time and after being briefed on the incident by US intelligence agencies and the country's nuclear weapons laboratories, he became convinced a nuclear test, in contravention to the Limited Test Ban Treaty, had taken place.

It was only after both the Carter and then the Reagan administrations attempted to gag him on the incident and tried to whitewash it with an unconvincing panel of enquiry, that it dawned on Weiss that it was the Israelis, rather than the South Africans, who had carried out the detonation.

"I was told it would create a very serious foreign policy issue for the US, if I said it was a test. Someone had let something off that US didn't want anyone to know about," says Weiss.

Israeli sources told Hersh the flash picked up by the Vela satellite was actually the third of a series of Indian Ocean nuclear tests that Israel conducted in cooperation with South Africa.

"It was a fuck-up," one source told him. "There was a storm and we figured it would block Vela, but there was a gap in the weather - a window - and Vela got blinded by the flash."

The US policy of silence continues to this day

There is now a panoply of published remarks by top U.S. spies deriding the White House panel report as a whitewash, and there has even been some sketchy confirmation of Israeli involvement, though it is less clear that South Africa participated. Israel's membership in the nuclear club is no longer a secret in any way, but is still an unmentionable for the U.S. executive branch.

In 1980 such talk had the potential to start a war. Students of the Vela Incident have, ever since then, been drifting pretty steadily toward the conclusion that it was a nuclear test. But if there is the equivalent of a smoking gun, we still cannot be sure which country or countries held it.

This article mentions the South African bomb so its a step in the direction of openness and transparency. That's progress. We should know our history, warts and all, or we will continue to make the same mistakes we have been making in recent decades.