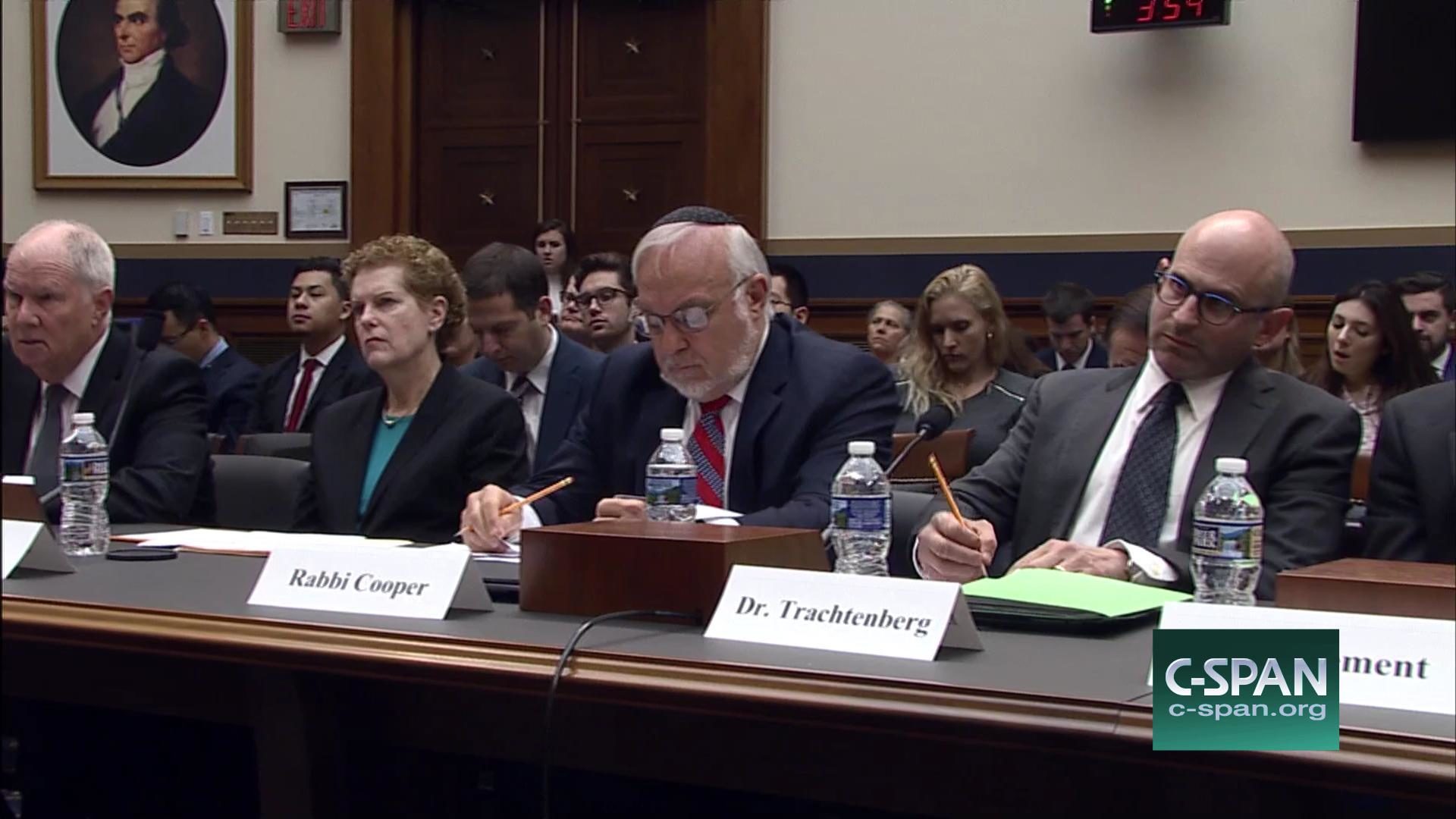

© C-SPAN

On November 7, the House Judiciary Committee held hearings over the Anti-Semitism Awareness Act,

a bill that would broaden the definition of antisemitism to include criticism of Israel. If passed, the legislation would instruct the Department of Education to consider the State Department's definition of antisemitism when investigating educational institutions for discrimination under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. The House Judiciary Committee heard testimonies in support of the bill from individuals representing institutions such as the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the Anti-Defamation League. Those who argued against the bill were Jewish Studies professors and representatives of advocacy groups.

During the question and answer portion of the hearing, an exchange between Rabbi Abraham Cooper of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Dr. Barry Trachtenberg, the Chair of Jewish History at Wake Forest University, was revealing and rooted in American Jewish history. Trachtenberg argued that the State Department's definition of antisemitism was deeply flawed

because it defines all accusations of American Jewish dual-loyalty as inherently antisemitic. By these standards, the ideas of Theodor Herzl could be defined as antisemitic. Herzl argued that because Jews represent one people, it is useless for them to be loyal to any other state but the proposed Jewish State.

Rabbi Cooper seemed to misunderstand the argument, reflexively accusing Trachtenberg of providing "cannon fodder for antisemites".

C-SPAN video available here.It is noteworthy that, in many ways, the exchange between Cooper and Trachtenberg mirrored the first time an American Jewish organization broached the topic of dual-loyalty after the establishment of Israel. The year 1949 marked United Jewish Appeal's "ingathering of the exiles" campaign. This Zionist philanthropic effort aimed at supplying the new state of Israel with American Jewish immigrants. In response to these calls from American Zionists and Israeli leaders, the American Council for Judaism, a group of anti-Zionist German-American Reform Jews, stated that these calls could bring up the question of dual-loyalty among antisemites. In response, virtually every major American Jewish organization, acting through an umbrella organization called the National Community Relations Advisory Committee, accused the ACJ of fueling antisemitism. Virtually every major English and Yiddish language periodical in the American Jewish press ran the NCRAC condemnation of the ACJ. By 1950, the ACJ found itself blacklisted.

Why, after six years of relative tolerance of similar ACJ members' statements, did American Jewish organizations react in such a way? I argue that during the height of the McCarthy era of American politics,

the dual-loyalty charge took on added sensitivity for American Jews. Beyond the accusation's traditional sensitivity, American Jews could then be seen as inherently loyal to a self-avowed socialist state. This accounts for the knee-jerk, defensive manner in which the NCRAC dealt with the charge. The NCRAC did not have any convincing evidence linking the ACJ to antisemitism at its disposal. During a period characterized by the blacklisting of those which McCarthists deemed un-American, American Jewish organizations stumbled upon antisemitism as a means to stifle potentially uncomfortable public debates among American Jews.

The issues of dual-loyalty and antisemitism get to the very precarious definitions of what it means to be simultaneously American, Jewish, and Zionist. Claims of gentile antisemitism were used by the UJA to urge American Jewish immigration to Israel in 1949. In contemporary times though, it is widely accepted that massive American Jewish immigration to Israel will not occur.

Yet the Herzlian notion that antisemitism is ubiquitous remains necessary for many supporters of Israel. However, instead of urging for the mass emigration of American Jews, claims of endemic antisemitism are used to stifle debate about Israel's long list of human rights abuses and illegal military occupation. The knee-jerk resort to charges and claims of antisemitism that began with the NCRAC in 1949 continue today.

- Voltaire.