The suit, filed by the nonprofit ArchCity Defenders law firm in U.S. District Court, says that St. Louis officials have ignored the problems for years. It seeks a judge's order that would close the workhouse or fine the city $10,000 per day until problems are fixed.

St. Louis Corrections Commissioner Dale Glass declined to comment about pending litigation Monday. But he rejected claims about mold and infestations of insects or rodents, and said guards were not being bitten by snakes and inmates were not being bitten by spiders.

He acknowledged that the 51-year-old jail is "showing signs of disrepair, but it's clean." Glass said there have been many improvements since 2012, but also said he's "never satisfied."

At a news conference Monday, James Cody, 43, of Jefferson City, said that there was typically only one working toilet, sink and shower for a 70-man dorm. He also complained of the heat, multiple cases of ringworm, a lack of fresh water and understaffing, but said his biggest fear was his safety at the workhouse.

Cody was held in the jail from Jan. 3 to Sept. 13 on a probation violation.

Diedre Wortham, 46, of St. Louis County, said being at the workhouse "made me feel like an animal. Like I was worthless."

Wortham, who has high blood pressure, said she didn't receive her medicine until a week before she was released on Aug. 9, after 23 days.

The suit says that summertime heat creates intolerable conditions, both for inmates and employees. Some dormitories have windows that have been boarded up or blocked, preventing ventilation. In others, there are no window screens, making mosquitoes, birds, and squirrels "a regular presence."

Ice and water is limited and that sparks conflicts among inmates, the suit says. Inmates, many of whom are too poor to afford bail, suffer dehydration, heat exhaustion, asthma attacks and heat rashes.

The suit does acknowledge that portable air conditioning units were supplied by the city this summer after a period of triple-digit heat indexes, but says officials have not come up with a permanent solution.

Glass said that another heat wave would trigger a return of temporary air conditioners, or a consideration of long-term solutions. But he said that a lack of air conditioning in local jails and state prisons is not unusual. He also said that windows were not boarded up when broken, but replaced with Plexiglass.

The suit says that "mold is a constant presence," and sinks and toilets regularly overflow. Inmates are not provided enough cleaning supplies to combat the problem, the suit says.

Cody found mouse feces on his food tray, the suit says, and mice would jump into inmates' beds. One inmate tried luring rats into a bag with peanut butter so he could manually kill them, it says.

Inmates also face inadequate medical treatment, the suit says, and are without a law library to research their cases.

The suit says Jasmine Borden, 32, of St. Louis, recalls the jail running out of toilet paper and feminine hygiene products for days at a time. The suit says at least five pregnant inmates had complications they blamed on mold and two women were bitten on the face by brown recluse spiders.

Most of the inmates are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of any crimes, according to the suit.

The suit says that "mold is a constant presence," and sinks and toilets regularly overflow. Inmates are not provided enough cleaning supplies to combat the problem, the suit says.

Glass said the workhouse population, at 551, is almost half what it was in 2012, when he started. He said he knows some want to close the jail, but the former Baptist minister says his goal is to have "no need" for it, by addressing mental health, substance abuse, poverty, despair and other factors.

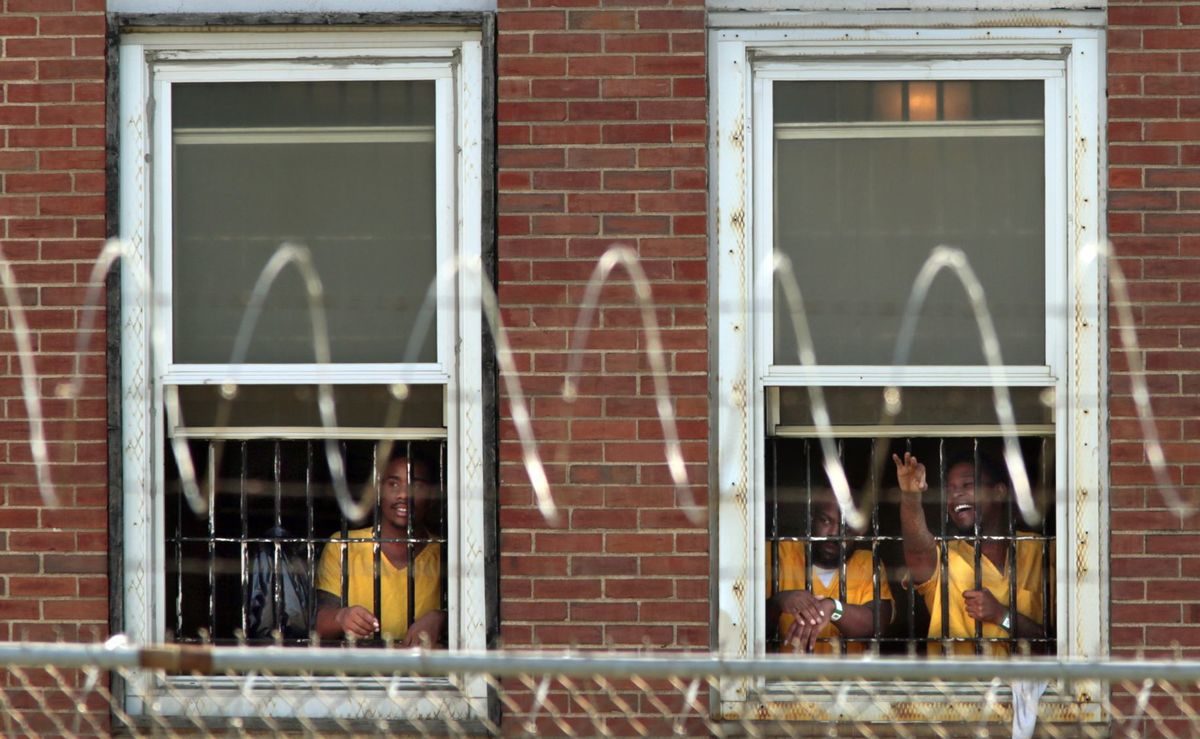

Jail conditions have sparked complaints for years.

In 2009, an American Civil Liberties Union report said the jail was overcrowded and unsanitary, and that staff and officials allowed inmates to assault each other, ignored sexual harassment, and provided negligent medical care.

In 2012, guards were accused of setting up gladiator-style fights between inmates.

This summer, protesters again demanded that the workhouse be shut down, in part because of the heat.

Among those raising concerns was Missouri state Rep. Joshua Peters, D-St. Louis, who has pushed for the Legislature to examine the conditions of the jail. Peters, who was also at the press conference along with other workhouse opponents, said that an April tour that he took with other legislators confirmed the inmate complaints in the suit. But he said he has been unable to get local or state officials to act.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter