But for most, that dream never becomes a reality. U.S. universities are seeing the rise of a growing underclass of poor, overeducated college teachers known as adjuncts, clinging to low-paid insecure jobs with little hope of advancing to the coveted ranks of the tenure track:

The Rise of the Part-Timers

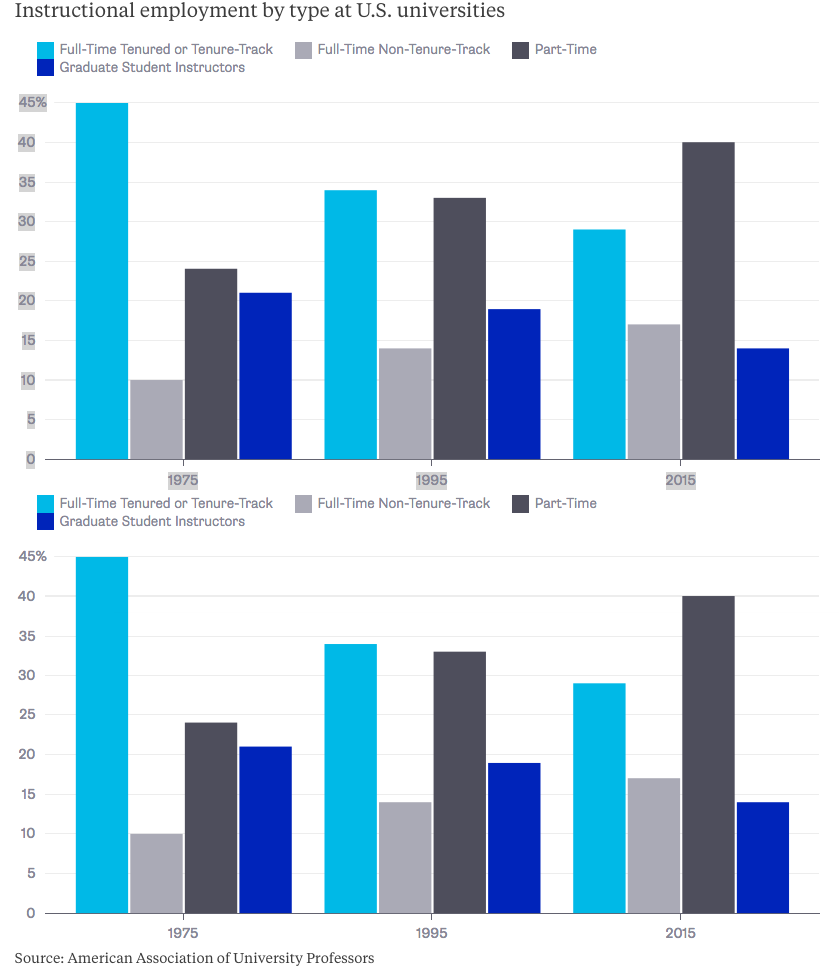

Instructional employment by type at U.S. universities

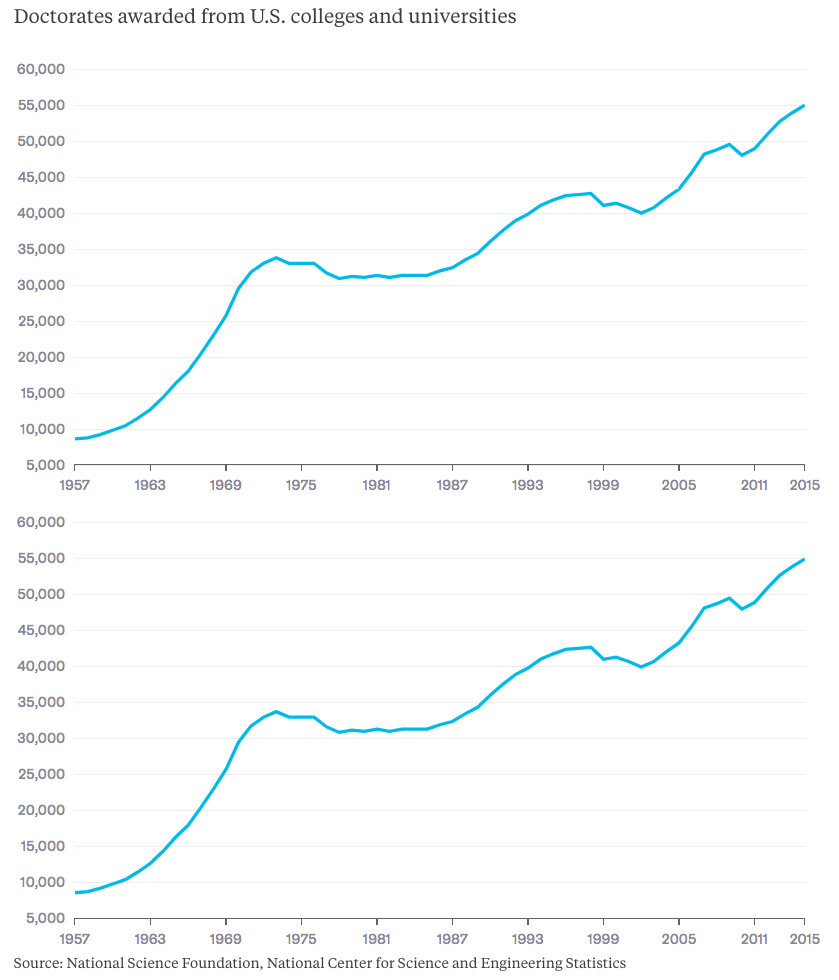

The raw numbers tell the same story -- tenured and tenure-track positions have increased by about a quarter since 1975, as the country has grown and the university system has expanded. But part-time positions have more than quadrupled. Meanwhile, the number of doctorates granted in the U.S. grew by about two-thirds:

Piling Higher and Deeper

This shift happened during a time when U.S. college tuition was soaring. Now college enrollment is stagnating or even falling, meaning that more tuition increases are unlikely. If universities were shifting toward adjuncts and away from the tenure track when times were booming, imagine what they'll do now, when they're forced to conserve their resources. If the tenure-track felt out of reach before, it's about to become even more illusory for all but a lucky few.

What is life like for an adjunct? Not great, according to New Faculty Majority, a website founded by pro-adjunct activists. In 2010, the median part-time college teacher pay had a full-time equivalent of $24,000 -- less than half the salary of the median kindergarten teacher. And not all part-time faculty can even get full-time work hours. Adjuncts also received essentially no wage premium based on their credentials -- in other words, so much for that advanced degree. Benefits were also minimal, with only 23.4 percent of part-time teachers at public universities receiving health coverage. Reports from the American Association of University Professors paint a similar picture.

For a graduate student, this kind of low-paid work can be just another cost of getting an education. But for an adjunct, it's a life of poverty. The Guardian ran a recent article about the harsh life of adjuncts, telling one anecdote about a middle-aged teacher turning to prostitution to pay the bills. Other stories include homelessness and dependence on food banks.

Why would a highly educated, skilled worker in a rich country such as the U.S. condemn herself to a life in the poorhouse? Surely, someone with the intellectual firepower to teach college students could get a job in digital-media marketing, or as a paralegal, or in any of the other middle-class occupations available to educated, hard-working Americans.

One answer is that adjuncts are making such sacrifices for the chance to pursue the academic dream. That would put academia in roughly the same class of occupations as acting and professional sports, where large numbers of unsuccessful lower-level aspirants struggle for years in the hopes of landing a coveted chance at a glamorous, high-status position.

But how many adjuncts really achieve that moonshot? I couldn't find data on the likelihood of making that leap, but anecdotally it's said to be unusual. And there are certainly several huge barriers in place. The first is simply long odds -- with the number of tenure-track positions barely growing and adjunct numbers exploding, the chance of going from the latter to the former keeps getting worse. Second, tenure-track jobs often the result of publishing research -- unlike grad students, adjuncts often hold other jobs and don't have a lot of extra time to work on papers. Third, in order to interview for tenure-track jobs, adjuncts typically have to pay their own travel costs and conference-registration fees (unlike other candidates). And fourth, there's the chance that a long career as an adjunct simply makes a candidate look less promising, even before age discrimination is taken into account.

There are other reasons to be a poor adjunct, of course. Some people undoubtedly love teaching college kids, and are willing to endure poverty in order to do it. Others are retired and need something to do. But it's possible that many adjuncts are desperately chasing an academic illusion that, realistically, they will never catch. Overoptimism is one of the most consistent findings in the psychology literature on behavioral biases.

There's also the cultural factor. Many people who go through the academic system idolize it. Their mentors and life advisers tend to be tenured professors, to whom doing anything other than academia probably sounds like failure.

What will end the misery of the adjuncts? Unionization helps improve pay and conditions a bit, but doesn't change the basic equation. Nor are universities likely to be morally shamed into treating adjuncts more like tenure-track faculty.

The only solution is for fewer people to go into the non-tenure-track college lecturing profession. Lower the supply of overoptimistic quasi-academics willing to endure relentless poverty to cling to the fading light of the university fantasy, and the wages of adjuncts should rise.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter