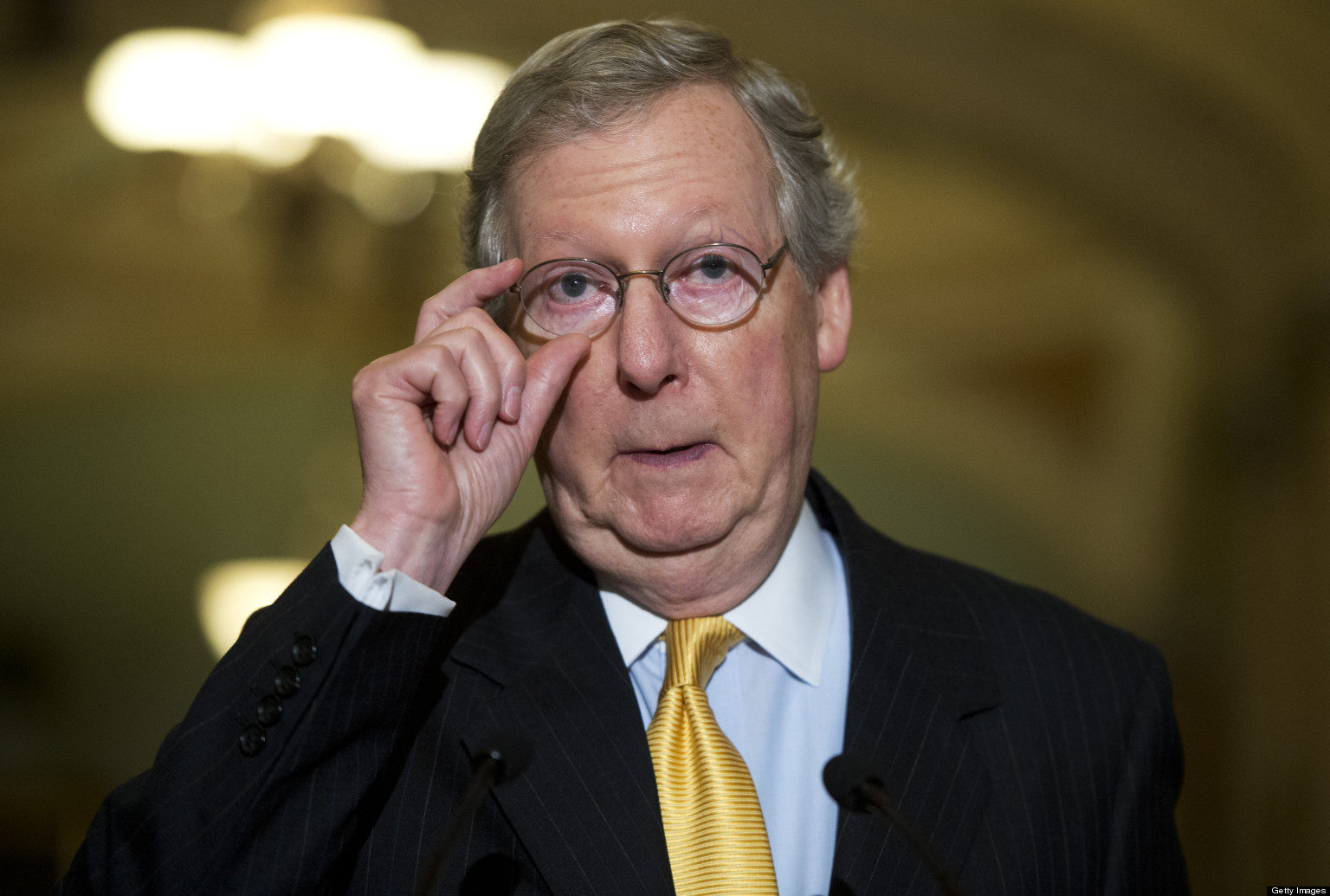

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.)

Mitch McConnell became leader of Senate Republicans at the precise moment it stopped mattering. It was January 3, 2007, and Democrats had just swept both the House and Senate in a wave election that was a thorough rejection of the GOP in Washington.

Even though the Bush administration had two years left, McConnell would be doing no governing from the minority during that time. Next came the election of Barack Obama, and McConnell's now-famous decision to oppose anything his administration offered with as much solidarity as could be mustered. With only 40 members to keep in line, he kept his conference largely together — though one glaring exception was losing Pennsylvania's Arlen Specter, not just on the stimulus, but as a Republican altogether. In April 2009, Specter became a Democrat, giving the party 59 senators. When Al Franken was finally sworn in in July, following an endless recount, Democrats briefly held a filibuster-proof majority.

The question now is whether Specter was the exception that proved the rule of McConnell's skill in leadership, or a forecast of things to come.

After three unsuccessful cycles, McConnell finally took back the upper chamber in 2014, but still did no governing, operating instead as an opposition party would in a parliamentary system. Just how ingrained that thinking was came through in a revealing comment from House Speaker Paul Ryan after his failure to repeal the Affordable Care Act. "Moving from an opposition party to a governing party comes with some growing pains," said Ryan, whose party had controlled the House for six years by that point. "And, well, we're feeling those growing pains today."

After Ryan pulled the original House ACA repeal from the floor, McConnell had a spring in his step as he addressed reporters. "Sorry that didn't work out,"

he offered. He was, of course, anything but sorry. For a brief moment, he thought he had dodged his own bullet.

After campaigning for six years on repealing Obamacare, the hope was that the failed House effort would be enough and the Senate could move on to the business of tax reform. But the House bill came back to life and the lower chamber passed the politically toxic potato across the Capitol to the Senate.The House bill was never designed to become law, and it's anything but clear that McConnell made a real effort to make it one. A decisive number of Republican senators from states that had expanded Medicaid, many of which are facing a cataclysmic opioid problem, were nervous about slashing the program. "Leadership made a strategic choice to side with conservatives on Medicaid from the outset, and that undermined just about any chance of them securing widespread support from key moderates," said one Senate Republican aide, who wasn't authorized to speak on the record.

To mollify the moderates, McConnell told them that the cuts would never actually happen, as Congress has a way of punting tough decisions like that in perpetuity. His comment was leaked, and Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., stunningly charged McConnell with a "breach of trust" for the suggestion.

This was the same Johnson that

McConnell and the Koch brothers abandoned for dead in July 2016, presuming that he would lose his race to Russ Feingold. He was down by nine points at the time, but Johnson pulled off an upset, and now haunts McConnell.

On Monday night, two GOP senators, Mike Lee of Utah and Jerry Moran of Kansas, announced simultaneously they would block McConnell's bill from coming up for a vote — McConnell's snake of obstruction finally devouring its own tail.

McConnell on Monday night floated a new plan: The Senate would vote on repeal, with no replacement. On Tuesday, three moderate women in McConnell's conference said they would block that vote, too. "I did not come to Washington to hurt people," West Virginia's

Shelley Moore Capito said.

Three is enough to kill it. "We're toast," as Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) put it to reporters on Tuesday.

At a lunch meeting Tuesday, White House chief of staff Reince Priebus showed up, only to duck out and hide behind a trash can.

As the meeting dragged on, Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., emerged and took the microphones that were waiting for McConnell, taunting his fellow Republicans with their past votes for repeal.

Sen. Pat Roberts, Moran's colleague from Kansas, pretended to take a phone call from President Trump, who was busy calling for the filibuster to be abolished — apparently under the mistaken impression that he needed 60 votes, not 50, to pass repeal.

"Hello, Mr. President," Roberts said into the phone as reporters laughed. "Well, the better approach is just to get the hell out of here," he advised the pretend president.

A subdued McConnell emerged later. "My suspicion is there'll be hearings about the crisis that we have and then we'll have to see what the way forward is," he said.

A reporter asked what he would tell the public about a wasted seven months and broken campaign promises. McConnell corrected him: it has been only six months. And we confirmed Neil Gorsuch.

"Well, we have a new Supreme Court justice. We have 14 repeals of regulation and we're only six months into it — the last time I looked, Congress goes on for two years. We'll be moving on to comprehensive tax reform and infrastructure," he said. "There is much work left to be done for the American people and we're ready to tackle it."

McConnell also promised a vote in "the very near future" on the doomed attempt to repeal much of Obamacare with no replacement.

Comment: Mitch has come under heavy criticism from colleagues for his lack of success with replacing Obamacare: