Like many American policies, U.S. Middle East policies are driven by a special interest lobby. However, the Israel Lobby, as it is called today in the U.S., consists of vastly more than what most people envision in the word "lobby."

[T]he Israel Lobby is considerably more powerful and pervasive than other lobbies. Components of it, both individuals and groups, have worked underground, secretly and even illegally throughout its history, as documented by scholars and participants. And even though the movement for Israel has been operating in the U.S. for over a hundred years, most Americans are completely unaware of this movement and its attendant ideology - a measure of its unique influence over public knowledge.

The success of this movement to achieve its goals, partly due to the hidden nature of much of its activity, has been staggering. It has also been at almost unimaginable cost. It has led to massive tragedy in the Middle East: a hundred-year war of violence and loss; sacred land soaked in sorrow. In addition, this movement has been profoundly damaging to the United States itself.

As we will see in this two-part examination of the pro-Israel movement, it has

- targeted virtually every significant sector of American society;

- worked to involve Americans in tragic, unnecessary, and profoundly costly wars; dominated Congress for decades;

- increasingly determined which candidates could become serious contenders for the U.S. presidency;

- and promoted bigotry toward an entire population, religion and culture.

The beginnings

The Israel Lobby in the U.S. is just the tip of an older and far larger iceberg known as "political Zionism," an international movement that began in the late 1800s with the goal of creating a Jewish state somewhere in the world. In 1897 this movement, led by a European journalist named Theodor Herzl, coalesced in the First Zionist Congress, held in Basle, Switzerland, which established the World Zionist Organization, representing 117 groups the first year; 900 the next.

While Zionists considered such places as Argentina, Uganda, the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, and Texas, they eventually settled on Palestine for the location of their proposed Jewish State, even though Palestine was already inhabited by a population that was 93-96 percent non-Jewish. The best analysis says the population was 96 percent Muslims and Christians, who owned 99 percent of the land.

After the Zionist Congress, Vienna's rabbis sent two of their number to explore Palestine as a possible Jewish state. These rabbis recognized the obstacle that Palestinians presented to the plan, writing home: "The bride is beautiful, but she is married to another man." Still, Zionists ultimately pushed forward. Numerous Zionist diary entries, letters, and other documents show that they decided to push out these non-Jews - financially, if possible; violently if necessary.

Political Zionism in the U.S.

The importance of the United States to this movement was recognized from early on. One of the founders of political Zionism, Max Nordau, wrote a few years after the Basle conference, "Zionism's only hope is the Jews of America."

At that time, however, and for decades after, the large majority of Jewish Americans were not Zionists. In fact, many actively opposed Zionism. In the coming years, however, Zionists were to woo them assiduously with every means at hand and the extent to which Nordau's hope was eventually realized is indicated by the statement by a prominent author on Jewish history, Naomi Cohen, writing in 2003, "but for the financial support and political pressure of American Jews... Israel might not have been born in 1948."

Groups advocating the setting up of a Jewish state had first begun popping up around the United States in the 1880s. Emma Lazarus, the poet whose words would adorn the Statue of Liberty, promoted Zionism throughout this decade. A precursor to the Israeli flag was created in Boston in 1891.

In 1887 President Grover Cleveland appointed a Jewish ambassador to Turkey (seat of the Ottoman Empire, which at that time controlled Palestine), because of Palestine's importance to Zionists. Jewish historian David G. Dalin reports that presidents considered the Turkish embassy important to "the growing number of Zionists within the American Jewish electorate. "Every president, both Republican and Democrat, followed this precedent for the next 30 years. "During this era, the ambassadorship to Turkey came to be considered a quasi-Jewish domain," writes Dalin.

By the early 1890s organizations promoting Zionism existed in New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Boston, Philadelphia, and Cleveland. Reports from the Zionist World Congress in Basle, which four Americans had attended, gave this movement a major stimulus, galvanizing Zionist activities in American cities that had large Jewish populations.

In 1897-98 Zionists founded numerous additional societies throughout the East and the Midwest. In 1898 they converged in a first annual conference of American Zionists, held in New York on July 4th. There they formed the Federation of American Zionists (FAZ).

By the 1910s the number of Zionists in the U.S. approached 20,000 and included lawyers, professors, and businessmen. Even in its infancy, when it was still relatively weak, and represented only tiny fraction of the American Jewish population, Zionism was becoming a movement to which "Congressmen, particularly in the eastern cities, began to listen."

The movement continued to expand. By 1914 several additional Zionist groups had formed, including Hadassah, the women's Zionist organization. By 1918 there were 200,000 Zionists in the U.S., and by 1948 this had grown to almost a million.

From early on Zionists actively pushed their agenda in the media. One Zionist organizer proudly proclaimed in 1912 "the zealous and incessant propaganda which is carried on by countless societies." The Yiddish press from a very early period espoused the Zionist cause. By 1923 every New York Yiddish newspaper except one was Zionist. Yiddish dailies reached 535,000 families in 1927.

While Zionists were making major inroads in influencing Congress and the media, State Department officials were less enamored with Zionists, who they felt were trying to use the American government for a project damaging to the United States. Unlike politicians, State Department officials were not dependent on votes and campaign donations. They were charged with recommending and implementing policies beneficial to all Americans, not just one tiny sliver working on behalf of a foreign entity. In memo after memo, year after year, U.S. diplomatic and military experts pointed out that Zionism was counter to both U.S. interests and principles.

While more examples will be discussed later, Secretary of State Philander Knox was perhaps the first in the pattern of State Department officials rejecting Zionist advances. In 1912, the Zionist Literary Society approached the Taft administration for an endorsement. Knox turned them down flat, noting that "problems of Zionism involve certain matters primarily related to the interests of countries other than our own."

Despite that small setback in 1912, Zionists garnered a far more significant victory in the same year, one that was to have enormous consequences both internationally and in the United States and that was part of a pattern of influence that continues through today.

Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the "Parushim"

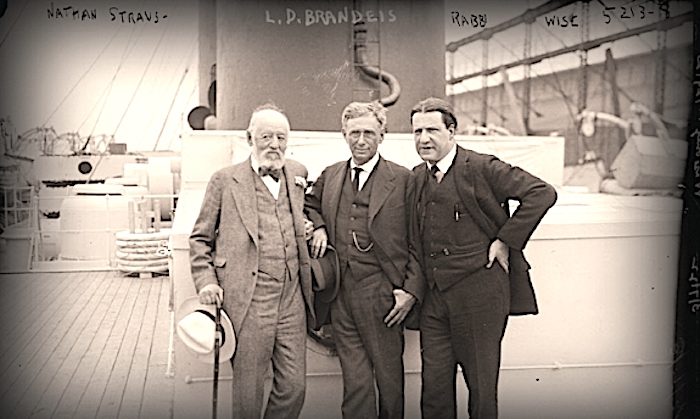

In 1912 prominent Jewish American attorney Louis Brandeis, who was to go on to become a Supreme Court Justice, became a Zionist. Within two years he became head of the international Zionist Central Office, newly moved to America from Germany.

While Brandeis is an unusually well known Supreme Court Justice, most Americans are unaware of the significant role he played in World War I and of his connection to Palestine. Some of this work was done with Felix Frankfurter, who became a Supreme Court Justice two decades later.

Perhaps the aspect of Brandeis that is least known to the general public - and often even to academics - is the extent of his zealotry and the degree to which he used covert methods to achieve his aims.

While today Brandeis is held in extremely high esteem by almost all of us, there was significant opposition at the time to his appointment to the Supreme Court, largely centered on widespread accusations of unethical behavior. A typical example was the view that Brandeis was "a man who has certain high ideals in his imagination, but who is utterly unscrupulous, in method in reaching them. "While today such criticisms of Brandeis are either ignored or attributed to political differences and/or "anti-Semitism,"there is evidence suggesting that such views may have been more accurate than Brandeis partisans would like.

In 1982 historian Bruce Allen Murphy, in a book that won a Certificate of Merit from the American Bar Association, reported that Brandeis and Frankfurter had secretly collaborated over many years on numerous covert political activities. Zionism was one of them.

"[I]n one of the most unique arrangements in the Court's history, Brandeis enlisted Frankfurter, then a professor at Harvard Law School, as his paid political lobbyist and lieutenant," writes Murphy, in his book The Brandeis/Frankfurter Connection: The Secret Political Activities of Two Supreme Court Justices. "Working together over a period of 25 years, they placed a network of disciples in positions of influence, and labored diligently for the enactment of their desired programs. This adroit use of the politically skillful Frankfurter as an intermediary enabled Brandeis to keep his considerable political endeavors hidden from the public," continues Murphy.

Brandeis only mentioned the arrangement to one other person, Murphy writes, "another Zionist lieutenant - Court of Appeals Judge Julian Mack."

One reason that Brandeis and Frankfurter kept the arrangement secret was that such behavior by a sitting Supreme Court justice is considered highly unethical. As an editorial in the New York Times pointed out following the publication of Murphy's book, "... the Brandeis-Frankfurter arrangement was wrong. It serves neither history nor ethics to judge it more kindly, as some seem disposed to do... the prolonged, meddlesome Brandeis-Frankfurter arrangement violates ethical standards."

The Times reiterates a point also made by Murphy: the fact that Brandeis and Frankfurter kept their arrangement secret demonstrated that they knew it was unethical - or at least realized that the public would view it as such: "They were dodging the public's appropriate measure of fitness."

Later, when Frankfurter himself became a Supreme Court Justice, he used similar methods, "placing his own network of disciples in various agencies and working through this network for the realization of his own goals." These included both Zionist objectives and "Frankfurter's stewardship of FDR's programs to bring the U.S. into battle against Hitler." Their activities, Murphy notes, were "part of a vast, carefully planned and orchestrated political crusade undertaken first by Brandeis through Frankfurter and then by Frankfurter on his own to accomplish extrajudicial political goals."

Frankfurter had joined the Harvard faculty in 1914 at the age of 31, a post gained after a Brandeis-initiated donation from financier Jacob Schiff to Harvard created a position for Frankfurter make a donation to Harvard to create a position for him. Then, Murphy writes, "for the next 25 years, [Frankfurter] shaped the minds of generations of the nation's most elite law students."

After Brandeis become head of the American Zionist movement, he "created an advisory council - an inner circle of his closest advisers - and appointed Felix Frankfurter as one of its members."

The Parushim

Even more surprising to this author - and even less well-known both to the public and to academics - is Brandeis's membership in a secret society that covertly pushed Zionism both in the U.S. and internationally.

Israeli professor Dr. Sarah Schmidt first reported this information in an article about the society published in 1978 in the American Jewish Historical Quarterly. She also devoted a chapter to the society in a 1995 book. Harvard author and former New York Times editor Peter Grose, sympathetic to Zionism, also reported on it in both in a book and several subsequent articles.

According to Grose, a highly regarded author, Brandeis was a leader of "an elitist secret society called the Parushim, the Hebrew word for 'Pharisees' and 'separate,' which grew out of Harvard's Menorah Society." Schmidt writes: "The image that emerges of the Parushim is that of a secret underground guerrilla force determined to influence the course of events in a quiet, anonymous way."

Grose writes that Brandeis used the Parushim "as a private intellectual cadre, a pool of manpower for various assignments." Brandeis recruited ambitious young men, often from Harvard, to work on the Zionist cause - and further their careers in the process.

"As the Harvard men spread out across the land in their professional pursuits," Grose reports, "their interests in Zionism were kept alive by secretive exchanges and the trappings of a fraternal order. Each invited initiate underwent a solemn ceremony, swearing the oath 'to guard and to obey and to keep secret the laws and the labor of the fellowship, its existence and its aims.'"

At the secret initiation ceremony, new members were told:

"You are about to take a step which will bind you to a single cause for all your life. You will for one year be subject to an absolute duty whose call you will be impelled to heed at any time, in any place, and at any cost. And ever after, until our purpose shall be accomplished, you will be fellow of a brotherhood whose bond you will regard as greater than any other in your life - dearer than that of family, of school, of nation."While Brandeis was a key leader of the Parushim, an academic named Horace M. Kallen was its founder, creating it in 1913. Kallen was an academic first hired by Woodrow Wilson, who was then president of Princeton, to teach English there. When Kallen founded the Parushim he was a philosophy professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Kallen is generally considered the father of cultural pluralism.

In her book on Kallen, Schmidt includes more information on the society in a chapter entitled, Kallen's Secret Army: The Parushim. She reports, "A member swearing allegiance to the Parushim felt something of the spirit of commitment to a secret military fellowship."

"Kallen invited no one to become a member until the candidate had given specific assurances regarding devotion and resolution to the Zionist cause," Schmidt writes, "and each initiate had to undergo a rigorous analysis of his qualifications, loyalty, and willingness to take orders from the Order's Executive Council." Not surprisingly, it appears that Frankfurter was a member.

'We must work silently, through education and infection'

Members of the Parushim were quite clear about the necessity of keeping their activities secret. An early recruiter to the Parushim explained: "An organization which has the aims we have must be anonymous, must work silently, and through education and infection rather than through force and noise." He wrote that to work openly would be "suicidal" for their objective.

Grose describes how the group worked toward achieving its goals: "The members set about meeting people of influence here and there, casually, on a friendly basis. They planted suggestions for action to further the Zionist cause long before official government planners had come up with anything." "For example," Grose writes, "as early as November 1915, a leader of the Parushim went around suggesting that the British might gain some benefit from a formal declaration in support of a Jewish national homeland in Palestine."

Brandeis was a close personal friend of President Woodrow Wilson and used this position to advocate for the Zionist cause, at times serving as a conduit between British Zionists and the president.

In 1916 President Wilson named Brandeis to the Supreme Court. At that time, as was required by standard ethics, Brandeis gave in to pressure to officially resign from all his private clubs and affiliations, including his leadership of Zionism. But behind the scenes he continued this Zionist work, quietly receiving daily reports in his Supreme Court chambers and issuing orders to his loyal lieutenants.

When the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) was reorganized in 1918, Brandeis was listed as its "honorary president." However, he was more than just "honorary." As historian Donald Neff writes, "Through his lieutenants, he remained the power behind the throne." One of these lieutenants, of course, was Frankfurter.

Zionist membership expanded dramatically during World War I, despite the efforts of some Jewish anti-Zionists, one of whom called the movement a "foreign, un-American, racist, and separatist phenomenon."

Alison Weir is Executive Director If Americans Knew and President of the Council for the National Interest.

Comment: The beginnings of the deep state, or a covert, ruling order? There is no doubt that Israel, with its infiltration of the USA and its hundreds - if not thousands - of subsidiary support organizations and social groups, has been and is still pulling the strings in Washington, according to the Zionist agenda for Israel.