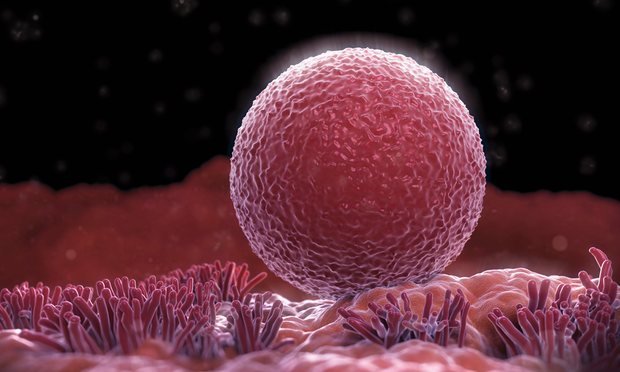

If confirmed, the discovery would overturn the accepted view that women are born with a fixed number of eggs and that the body has no capacity to increase this supply. Until now this has been the main constraint on the female reproductive lifespan. The findings, if replicated, would raise the prospect of new treatments to allow older women to conceive and for infertility problems in younger women.

The small study, involving cancer patients, showed that ovarian biopsies taken from young women who had been given a chemotherapy drug had a far higher density of eggs than healthy women of the same age.

Prof Evelyn Telfer, who led the work at the University of Edinburgh, said: "This was something remarkable and completely unexpected for us. The tissue appeared to have formed new eggs. The dogma is that the human ovary has a fixed population of eggs and that no new eggs form throughout life."

Her team initially set out to investigate why the drug, called ABVD, does not cause fertility problems, unlike many forms of chemotherapy.

Although the research is promising, Telfer warned against the apparent eagerness of some fertility clinics to offer novel treatments before the basic science is well understood.

"There's so much we don't know about the ovary," she said. "We have to be very cautious about jumping to clinical applications."

The findings have been greeted with a mixture of excitement and scepticism.

"I think that these findings, and the identification of the mechanisms involved, may pave the way for development of new fertility treatments or extend women's reproductive span by replenishment of the ovaries with new follicles," said Kenny Rodriguez-Wallberg, a senior consultant at the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm. "It suggests that the ovary is indeed a more complex and versatile organ than we have been taught, or that we expected, with an inherent capacity of renewal."

Others, including David Albertini, laboratory director at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York, were less convinced. "Honestly, I think there are too many other ways to explain the results, one of which is that new eggs were made," he said.

Other possible explanations might be that the eggs were already there and rose to the surface when the ovary was stressed by the treatment, or that egg follicles split into two or more parts due to damage from the treatment. The results should be seen as a curiosity rather than a discovery until replicated and investigated further, Albertini said.

The study compared ovarian biopsies from Hodgkin lymphoma patients, eight of whom had been given ABVD and three of whom had given a stronger drug combination (OEPA-COPDAC) known to cause infertility, and also samples from 10 healthy women.

The patients who had undergone the ABVD treatment had between double and four times the density of visible eggs in the ovarian tissue than the control group, while those given the other drug had far fewer. "It's a big increase, not just a few," said Telfer. "We have no other explanation than that new eggs have been formed."

Telfer said that the results stop short of proving that new eggs had been generated - but that this is her favoured explanation, because it fits in with other clues.

Eggs from the ABVD patients appeared "younger"- more like eggs seen in pre-pubescent girls - consistent with the idea that they were newly formed and had not fully matured. They also grew less well than those from the those from the control group, although these patients are known not to have fertility problems.

Previously Telfer's group has identified what appear to be stem cell populations in the ovaries that can be grown into egg-like cells in the lab. However, it is not clear yet whether these cells are functional eggs that could be fertilised - and even the existence of a ovarian stem cell reserve is disputed by other scientists.

Nick Macklon, professor of obstetrics and gynaecology within medicine at the University of Southampton, said that the work "raises more questions than it answers".

"It's hugely controversial, this work," he said. "Evelyn would take the view that there are these stem cells there. This [new study] could be some evidence that it might be possible."

Macklon echoed Telfer's concerns that some clinics are too quick to pounce on any intervention that might boost the success rate of their treatments. "The slight worry is that clinicians are very quick to pick up anything that will improve IVF," he said. "There's no evidence at this stage that these drugs would improve the odds for people who are having a poor response to IVF drugs."

The findings were presented at the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology annual conference in July and are described in a journal paper that is in review.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter