Santa, dear Santa, don't say ho-ho-ho. Just say no-no-no.

To smoking, that is.

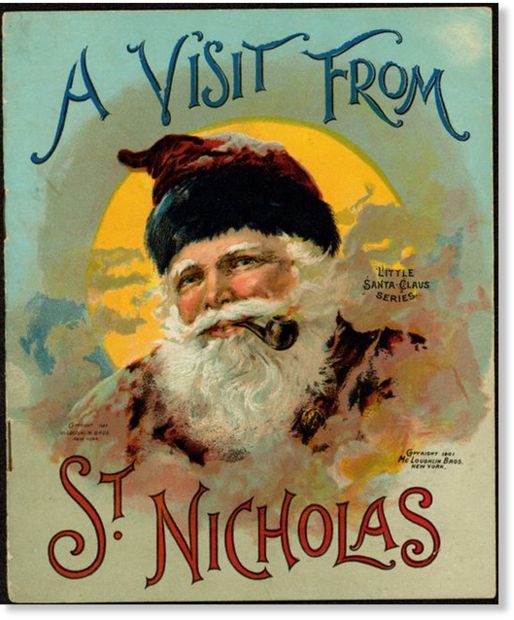

That is the plea of a Canadian entrepreneur, who has self-published an abridged version of "'Twas the Night Before Christmas," the poem also known as "A Visit from St. Nicholas" and "The Night Before Christmas."

First published anonymously in 1823, the poem is generally attributed to New York scholar Clement Clarke Moore (though at least one academic believes it was written by a distant relative of Moore's wife).

Generations of children have grown up reading this poem on Christmas Eve. It has inspired many of the ideas we hold about Santa, a "right jolly old elf" who drives a reindeer-powered sleigh full of toys and enters homes via chimneys to deliver those toys on Christmas Eve.

With its vivid rendering of Santa - his roselike cheeks, cherrylike nose, and a belly that shakes, when he laughs, "like a bowl full of jelly" - the poem is pure joy in verse form.

Alas, not everyone sees it that way.

According to media reports, Pamela McColl, of Vancouver, Canada, thinks "'Twas the Night Before Christmas" has been a very bad influence on tender young minds. And in her edition of the poem, she has deleted mention of Santa's tobacco use.

Santa no longer holds a stump of a pipe "tight in his teeth." No smoke encircles "his head like a wreath."

Her version, McColl rather presumptuously states on her book's cover, has been "edited by Santa Claus for the benefit of children of the 21st century."

The book's dust jacket features a note purportedly written by Santa: "Here at the North Pole, we decided to leave all of that tired old business of smoking well behind us a long time ago. The reindeer also asked that I confirm that I have only ever worn faux fur out of respect for the endangered species that are in need of our protection."

To borrow from another Christmas classic, this is humbug.

I've never smoked, and I wouldn't want my kids to smoke, so I appreciate the efforts of anti-smoking advocates who are trying to keep youngsters away from tobacco.

And I'm not completely opposed to political correctness: Sometimes, what's derided as political correctness is actually a matter of politeness.

But according to a statement from the American Library Association, quoted by the Associated Press, McColl practiced a form of censorship when she altered "a classic work of literature with a view toward protecting modern sensibilities, or preventing children from being aware of the character of the original work."

And to what aim? Does anyone seriously think that a poem's reference to a pipe-wielding Santa has led generations of children to become smokers?

If so, what other harmful behaviors might this poem be encouraging in our kids?

St. Nick is clearly obese, and obesity, we all know, is the most pressing threat to children's health.

Instead of holding Santa up as a paragon of good behavior - our go-to arbiter of what's naughty and what's nice - shouldn't we be tsk-tsking about his sugar addiction?

I'm not suggesting that we fat-shame Santa, but perhaps we ought to offer him a gentle hint by leaving him crudités and nonfat Greek yogurt instead of sand tarts on Christmas Eve.

And we certainly ought to make it clear to our children that just because Santa has no discipline, that doesn't mean we can overdo it with the peppermint bark and cocoa.

While we're at it, we might want to point out to our kids that "jolly" is often a euphemism for "fat." So they shouldn't call their great-aunt Sally jolly. She might not like it.

The aptly surnamed Beth Kitchin, an assistant professor of nutrition sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, wrote in a recent blog post that Santa's plumpness might not be a terrible thing, as long as he exercised regularly.

"There is evidence that older people often do better with a little extra weight," Kitchin noted. "While we do not know Santa's exact age, sightings of St. Nick date from the 16th century, making him possibly hundreds of years old. Weight loss in an elf his age could lead to osteoporosis, fractures and malnutrition, and who wants that for Father Christmas?"

In "'Twas the Night Before Christmas," Santa is described as being "so lively and quick." His spryness suggests he's getting regular exercise, so perhaps we need not worry about his caloric intake.

But what of his driving habits? They strike me as being a little suspect.

His reindeer are described as being "more rapid than eagles." Do they adhere to the speed limit for sleighs pulled by flying reindeer? How rapidly do eagles fly, anyway?

We're also told that Santa and his team fly away "like the down of a thistle." Have you seen the down of a thistle disperse? I have. It goes in all directions. Is Santa under the influence of more than just milk and cookies?

Clearly, this classic Christmas poem raises as many questions as it answers.

This is the season of goodwill, so I trust McColl was being truthful when she told the Vancouver Sun that her abridged version of "'Twas the Night Before Christmas" was not merely a cynical attempt to create a controversy over a beloved poem, but a sincere effort to advance a cause she takes seriously.

That newspaper reported that when she was 18, McColl "had to flee her family home when her father fell asleep in bed with a lit cigarette and the house was engulfed in flames." As that paper tells it, she became a smoker herself, and didn't quit until she became pregnant with twins.

So fleeing her burning home wasn't enough of a deterrent? But a tobacco-free version of "'Twas the Night Before Christmas" will be?

According to the Vancouver Sun, more than 75,000 digital copies of McColl's book have sold since September, and she is determined to see her version entrenched in the English language.

I'm hoping that devoted readers of the unabridged poem just say no, no, no to that.

Comment: Pamela McColl clearly exhibits the traits of an authoritarian follower. For information about the benefits of tobacco, please read:

Nicotine - The Zombie Antidote

Let's All Light Up!

First They Came for the Smokers... And I said Nothing Because I Was Not a Smoker

Study finds smoking wards off Parkinson's disease

Nicotine helps Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Patients

Nicotine Lessens Symptoms Of Depression In Nonsmokers

Scientists Identify Brain Regions Where Nicotine Improves Attention, Other Cognitive Skills

Can Smoking be GOOD for SOME People?