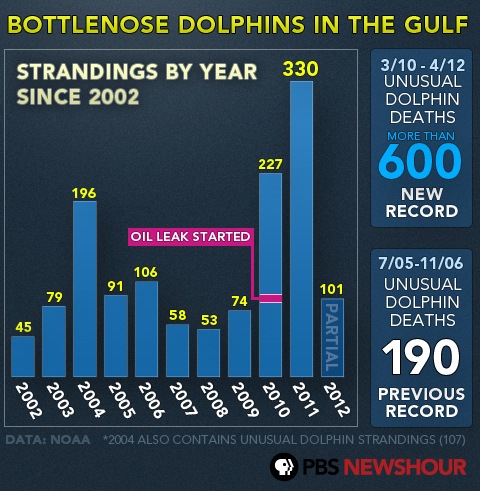

More than 100 dolphin strandings already this year add to a pattern of death and disease among the marine mammals. In a normal year before the spill, about 74 strandings would be reported in the area. That number has increased eightfold in the past two years. Since February 2010, more than 600 have been found on the shores between the Louisiana-Texas border and the western coast of Florida.

And many of these dolphins have serious health problems -- lung disease, liver problems and low blood sugar -- according to autopsies on the animals and other research.

Scientists suspect oil as a major culprit, but linking the spill definitively with the dolphin die-offs has been tricky. Decomposition causes tissue to decay, making the animals difficult to study.

"In all of the dolphin deaths... only 17 percent are stranded alive or stranded in fresh-dead conditions," said Jenny Litz, a research fishery biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who is studying the die-offs. Decomposition makes it much harder to study tissues during a necropsy (A necropsy is the animal equivalent of an autopsy).

There's another fact that complicates the picture. The number of deaths began to rise in March 2010, shortly before the spill. After the spill, the number continued to climb, and the period since represents the longest-lasting dolphin die-off in the Gulf of Mexico, at 25 consecutive months. But the increase just before the spill suggests that other factors may also play a role, such as ocean pollution, or a disease some animals tested positive for called brucellosis, a bacterial infection not typically associated with mass dolphin death. This complicates both investigation into the strandings as well as an impending litigation against BP, Litz said.

Still, it certainly appears that oil is at least partly to blame, Michael Jasny, Senior Policy Analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said.

"It's circumstantial evidence, but it's still very, very strong," he said. "The highest number of dolphin strandings have occurred in areas hit hardest by exposure to BP oil."

Historically, dolphin strandings peak between February and May, which is prime calving season. Consider some of these numbers from before and after the spill:

The average number of infant dolphin deaths or stillborns before 2010 was about 14. In 2010, that number jumped to 29. The following year saw 86 dolphins that were either premature, stillborn or stranded infants. Now that it's peak calving season, that number is once again on the rise."It's really quite astonishing," said Jasny. "It suggests that something is deeply wrong with fetal or maternal health."

Toxic compounds ingested by dolphins in oil-contaminated water could contribute to the rise in stillbirths, he said.

"Dolphins live very high on the food chain," Jasny added. "Fish are eating smaller fish, and smaller fish are eating plankton. All of those toxins work their way through each of these organisms in the food chain. So it's a bioaccumulation in the tissues of the top-feeders--dolphins."

But Litz maintains that it's still too soon to tell just what effect oil might be having on dolphin babies in the Gulf, stressing that in most populations, there is a higher mortality rate around birth.

While much of the NOAA-led investigation under the Natural Resource Damage Assessment process is ongoing, scientists are studying the effects oil in the water can have on dolphins.

Randall Wells, director of the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program at Mote Marine Laboratory, compared sick or stranded dolphins in Barataria Bay, an area off the coast of Louisiana that was heavily affected by the oil spill, with a healthy population of bottlenose dolphins in Sarasota Bay, an oil-free area.

"Prior to this, there were studies that show dolphins probably can detect oil in the water," Wells said. "Under most circumstances, they mostly avoid it." But, he adds, that would happen only if the dolphins have had previous experience with oil in their environment. "Even if they can detect it, they might not have known to avoid it."

In addition to lung disease and liver problems, Wells and his team found that many of the dolphins were anemic and suffering from low blood sugar and low stress hormones.

He pointed to continuous pollution in the Gulf of Mexico, rather than just the BP oil spill in particular, as a contributing factor to the deteriorating health of these marine mammals.

The nation's track record with the environment and fragile coastlines needs to change, Jasny said: "There are clear lessons to be learned from what is happening in the Gulf. It is obscene that we are not learning them."

is that the suppositions come from the publicised onset of the Deepwater Horizon explosion and not before where many things may have occured well before the "well publicised" DH explosion - I am cynical enough to believe that the Gulf issue happened well before the DH event and that acustic soundings or airgun activities could also be creating damages on a long term basis that would create the reduction in dolphin dynamics.

Put it another way -what goes on under the water is never seen until its too late - the lying is legion and the interests and agendas particular.