- Fuel rods appear to be melting inside three over-heating reactors

- Experts class development as 'partial meltdown'

- Japan calls for U.S. help cooling the reactor

There is a risk that molten nuclear fuel can melt through the reactor's safety barriers and cause a serious radiation leak.

There have already been explosions inside two over-heating reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant, and the fuel rods inside a third were partially exposed as engineers desperately fight to keep them cool after the tsunami knocked out systems.

Japanese chief cabinet secretary Yukio Edano said it was 'highly likely' that the fuel rods inside all three stricken reactors are melting.

Some experts class that a partial meltdown of the reactor, but others would only use that term for when molten nuclear fuel melts through a reactor's inner chamber - but not through the outer containment shell.

As fuel rods melt, they form an extremely hot molten pool at the bottom of the reactor that can melt through even the toughest of containment barriers.

Japan is fighting to avoid a nuclear catastrophe after the tsunami. There was a hydrogen explosion at the reactor in Unit Three of the power station earlier today, in which eleven workers were hurt by the blast that was felt 25 miles away.

The reactor at Unit One of Fukushima exploded on Saturday, blowing several walls away but engineers said the core was still contained. The fuel rods in the reactor in Unit Two of the plant were partially exposed from their coolant today - which also increases the risk of meltdown.

Engineers have been fighting to keep the reactors under control after the tsunami knocked out emergency coolant systems on Friday.

Earlier engineers were frantically trying to cool radioactive materials at all the reactors with seawater but had halted the process, which resulted in a rise in radiation levels and pressure.

Plant managers knew an explosion was a possibility as they struggled to reduce pressure inside the reactor containment vessel in Unit Three, but apparently felt they had no choice if they wanted to avoid a complete meltdown.

In the end, the hydrogen in the released steam mixed with oxygen in the atmosphere and set off the blast, which was felt 25 miles away.

The plant's operator Tokyo Electric Company said radiation levels at the reactor were still within legal limits.

Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said the Unit Three reactor's inner containment vessel holding nuclear rods is intact, allaying some fears of the risk to the environment and public.

The government had warned that a further explosion was possible because of the build-up of hydrogen in the building housing the reactor.

More than 180,000 people have been evacuated from the area.

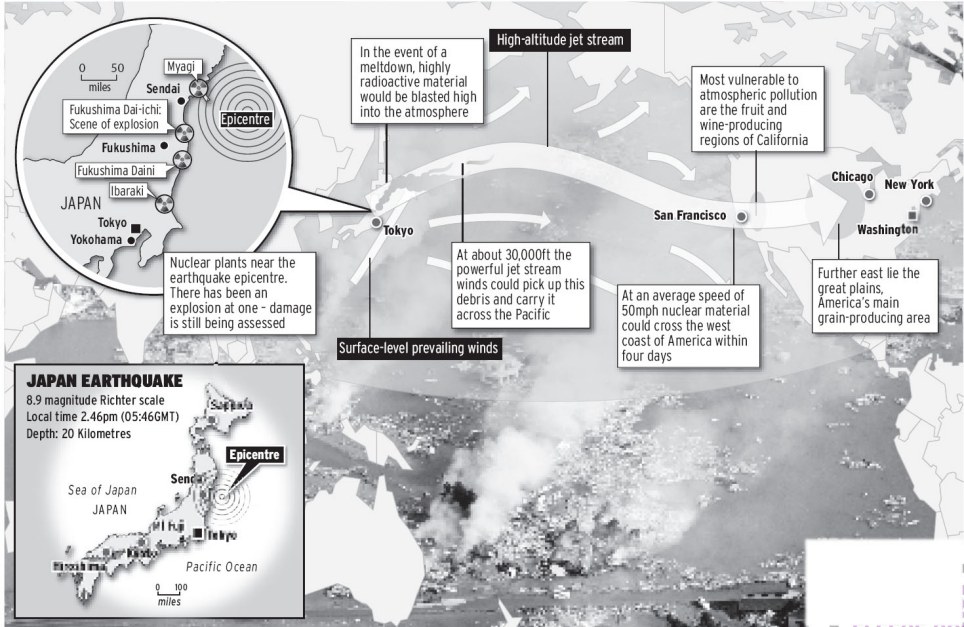

Californian officials are monitoring the situation, amid fears that radioactive material could be blown across the Atlantic to the U.S. if there is a large leak.

However, the winds could shift and hit a different part of the U.S.

Michael Sicilia, spokesman for California Department of Public Health, said: 'We are monitoring the situation closely in conjunction with our federal partners.'

In the event of a major leak, radiation would take between seven and 10 days to cross the Atlantic.

In Japan earlier a state of emergency had been declared after the high levels of radiation were detected at the nuclear power complex.

Thousands of families have been evacuated and many more were yesterday being checked for radiation exposure as Japan began to take stock of what the prime minister labelled its 'most severe crisis since the Second World War' - when the U.S. dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Tens of thousands are feared dead, with bodies being picked up from beaches along a 300-mile stretch of coastline.

Others are being gathered from the sea and thousands more are believed to lie buried deep in mud under the debris of homes and cars. At least 10,000 people - half the population of the port of Minami Sanriku - were unaccounted for and the town has been virtually wiped off the map.

Nearby Rikuzentakata was also swamped and destroyed by Friday's tsunami, killing at least 400 people.

Hundreds of Britons - many of them English language teachers - are among the missing.

Some 100,000 troops and civil defence members, backed by ships and helicopters, yesterday began the mammoth task of clearing rubble and searching for survivors and bodies.

So many people died because when the nine-magnitude Pacific Ocean earthquake struck 80 miles off the coast of Sendai, warnings were issued that a tsunami would hit land in an hour.

But survivors said it struck in nine minutes.

There were warnings last night that strong aftershocks, with a magnitude of six or more, could be expected for at least another week - and Tokyo shuddered several times yesterday as a series of shocks struck the city.

But the gravest consequence of the earthquake and tsunami could yet be felt, as scientists frantically tried to control the threat of nuclear meltdown.

Men in white protective suits and masks swept Geiger counters over frightened survivors yesterday as nuclear experts around the world monitored the crippled and unstable Fukushima plant, 150 miles north of Tokyo.

Up to 200,000 people were evacuated from within a 12-mile radius of the plant, which remains the biggest threat.

And the words designed to reassure the public that they were in no danger from any leaked radiation were at odds with those from the operator of the plant, Tokyo Electric Power.

The company conceded that radiation levels around the complex had risen above the safety limit but tried to appease the public by stating that it did not mean an 'immediate threat' to human health.

It also emerged yesterday that the government ignored explicit warnings from a Japanese expert on nuclear power more than three years ago.

Professor Ishibashi Katsuhiko, of Kobe University, said the guidelines introduced to protect the nuclear plants were 'seriously flawed' and that the plants were vulnerable to major quakes.

'Unless radical steps are taken now to reduce the vulnerability of nuclear power plants to earthquakes, Japan could experience a true nuclear catastrophe in the near future,' he warned in 2007.

Elsewhere, millions of people are without power and water, factories will remain closed for weeks and Tokyo has been warned there will probably have to be power cuts to conserve electricity.

At rescue centres in Sendai, where people prepared for a third night sleeping on the floor, notice boards are cluttered with the names of the missing.

Weeping survivors said they could only pray that poor communications had failed to put them in touch with their loved ones. One elderly woman reading through one of the lists suddenly exclaimed:'That's me! They say I'm missing. Well, here I am. My sons must be worried sick about me. But I'm OK.'

Rail services to Sendai and beyond were postponed indefinitely and the only way anyone had any hope of reaching the stricken region was by air, flying to towns on the west coast and attempting to drive across the island. But police have blocked many roads, to keep them clear for rescue vehicles and ambulances.

From the air, rail carriages could be seen lying on their sides. Cars and houses were piled up like debris thrown on to a huge rubbish tip.

So how alarmed should we be over this crisis?

Enthusiasts for atomic power are today, inevitably, on the back foot. Those who argue that in the normal course of things nuclear energy is the safest and most reliable form of energy have to contend with a single word: 'meltdown'.

This is a scenario that brings dread to the hearts of nuclear engineers - an uncontained chain reaction in a reactor core, a blob of molten radioactive metal burning its way out of the containment chamber and a massive release of radioactive fission products such as iodine-131 and strontium-90 into the environment.

It was a partial meltdown which led to the Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania in 1978, and a similar explosive breakdown that caused the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

Both incidents brought strident calls to abandon nuclear power altogether - calls which are bound to intensify following the still-unfolding Japanese catastrophe.

On top of the worst earthquake in its history and a tsunami which may have killed tens of thousands, Japan - a nation which for obvious reasons after the events of 1945 has a love-hate relationship with nuclear power - is staring into the atomic abyss.

What actually caused the accident at Fukushima is still unclear but it seems that in simple terms, the power station was hit by a power cut.

First, seismic detectors at the plant, alerted by the earthquake, triggered an automatic shutdown - by inserting boron rods into the reactor cores, stopping the heat-producing fission reaction.

Normally, the reactor fuel would simply have cooled down safely over a matter of days. But then the tsunami swept through local power grids and back-up generators which provided the electricity for the reactor cooling pumps - possibly fracturing the water main into the plant as well.

Like a car engine with a leaking radiator, the heat started to build up to dangerous levels. Nuclear power stations are essentially huge kettles. You have a power source - the nuclear reactor itself - which gets hot; several hundred degrees in a controlled fission reaction.

The heat is produced by the fission - splitting - of atoms of radioactive materials, such as uranium.

This produces not only heat but radiation, and also the creation of radioactive by-products which themselves emit heat as they undergo radioactive decay.

This explains why, even if the primary nuclear reaction is stopped, heat will continue to be generated for days - enough to melt the reactor core if it is not cooled. In normal operation, all this heat is useful - it is used to boil water, which makes steam that is then used to drive electricity-generating turbines.

The problem is that you cannot simply turn off an atomic reactor instantly. It takes days for the red-hot fuel rods to cool down - and that is provided they are supplied with adequate coolant.

Professor Richard Wakeford, a nuclear expert at Manchester University, said yesterday: 'If the fuel is not covered by cooling water it could become so hot it begins to melt - if all the fuel is uncovered you could get a large-scale meltdown.'

Hopefully this will not happen, and thanks to both the design of the Japanese reactors and to the swift and organised response of the authorities, handing out iodine pills to prevent the ingestion of cancer-causing substances, there is little chance that Fukushima will enter the annals of notoriety alongside Chernobyl.

One possibility which can be discounted is the so-called 'China Syndrome', the wholly fictitious idea that a molten reactor core could melt its way through the Earth and emerge on the other side. It is now known that even a total meltdown, although deadly, would soon be contained and cool down naturally. But already questions are being asked - about Japan's nuclear safety record, and what implications this has outside Japan.

Was it wrong to build a series of atomic reactors so close to the ocean? Experts suggest that given the whole country is an earthquake zone, there is nowhere the plant could be built which would not be at risk.

Unlike Chernobyl, there is no chance that this could become an international incident; Japan is simply too far away from anywhere else for the radiation to spread, and the most serious radioactive contaminant - Iodine-131 - has a half-life of just eight days. Furthermore, the Japanese government is rich, competent and open - which the Soviet authorities in 1986 conspicuously were not.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter