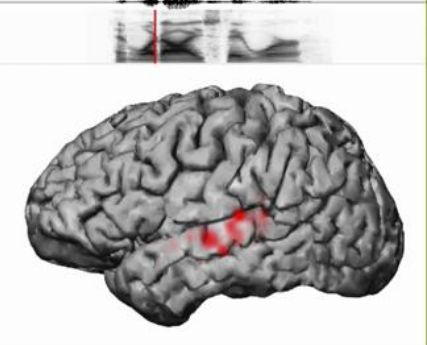

- Researchers looked for presence of nanodiamonds in Oklahoma

- Nanodiamond is one type of material that could result from a collision

- 49 sediment samples representing different time periods were studied

- Team found nanodiamonds below and just above Younger Dryas deposits

- Younger Dryas, or the 'Big Freeze', saw a return to glacial conditions in higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere 12,900 - 11,500 years ago

This is according to a controversial study by Californian Professor James Kennet which suggests that an ancient cosmic impact triggered a vicious cold snap.

Now a research team from University of California, Santa Barbara, claims to have further evidence to back up Professor Kennett's 2007 'Younger Dryas impact theory'.

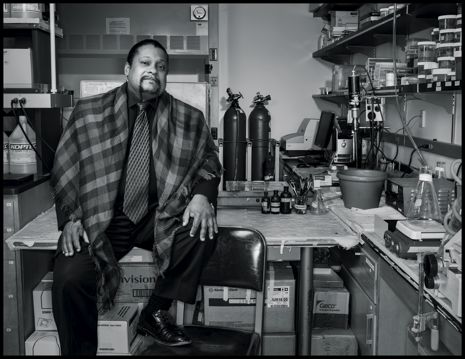

Comment: In February of 2012 an excellent article about Dr. Tyron Hayes and his ongoing battle with Syngenta over the growing concerns about the controversial herbicide atrazine, was published in Mother Jones Magazine and carried on SOTT.net: The Frog of War.