Minden, West Virginia, is in a small holler — hollow, to non-Appalachians — and 40 years ago it was home to about 1,200 people. Today it's home to 250. There are around 25 homes on the main road into town, mostly low-slung or trailers, and we drove slowly so Worley-Jenkins had time to recount the dead.

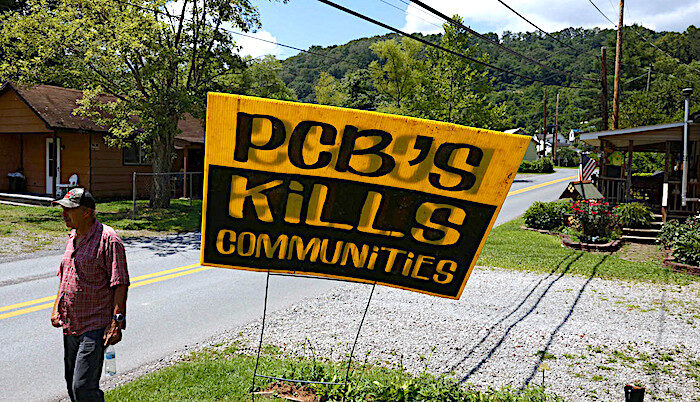

"This woman here, she died of cancer. Her son's right there now, he's dying with bone cancer. And the woman there died of cancer. This guy and his wife both died with cancer; he bought this to fix it up. He was our sheriff."Minden was born a coal town. Five decades ago, the Shaffer Equipment Company, which serviced the local coal industry, dumped its transformers into the abandoned mines above town. The machines were laced with extremely toxic industrial chemicals called polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, classified by the Environmental Protection Agency as probable human carcinogens.

"The lady that lived here, let's see, she's got breast cancer. The lady lived there just died. The guy there has real bad breathing problems and has cancer, dealing with it now, too. I have all these names. In the last two or three years, there's been 160 that died or has cancer."The creek we drove along snakes through town and across property lines, and today it was swollen, fouled with rain-driven runoff from the toxic mines above it. A miscarriage on the right, blood disorders on the left, hundreds of cancer cases everywhere.

Late winter snow drifted through a broken window into a burned-out home, abandoned since the occupants died. All told, Worley-Jenkins figures, at least 500 residents have died unnatural deaths in the last two decades. "Now you see why we're so pissed off."

For anyone who'd been watching Pruitt over the years, it felt like a joke.

At the time, I was covering the EPA's aggressive deregulatory efforts for Outside magazine, and the environmentalists I interviewed scoffed at the Superfund proclamation. The Trump administration would dedicate itself to remediating the most polluted parts of the country, they said, while simultaneously rolling back regulations designed to stanch pollution? The movement collectively rolled their eyes and went back to the dreary work of suing the agency to halt rule changes and scraping government websites for climate data before it could be deleted.

Still, no one denied that the aging Superfund program was in trouble. The billion-dollar cleanup program, birthed by the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, gives the EPA enormous power to compel polluters to clean up their own messes. Early in its life, it was touted as the most potent environmental rule anywhere. But decades of systemic underfunding and neglect have slowly neutered Superfund.

In the late 90s, during President Bill Clinton's second term, the EPA averaged 87 completed cleanups per year; over the first six years of the George W. Bush administration, the number dipped to 40; Obama's first year in office saw 20 completed clean ups and in 2014 the number dived to a piddly eight. By the tail-end of the Obama years there were still 1,300-plus sites on the Superfund National Priorities List — the worst of the worst — and some 53 million people living within three miles of one. The program "was neglected in the Obama administration," Brett Hartl, the Center for Biological Diversity's government affairs director, told me. "Not maliciously, but neglected."

But then, as the Trump administration slashed water regulations and defunded climate research, something strange happened: Pruitt appeared to be delivering on his Superfund promise. Top officials took a personal interest in dozens of sites across the country. Stalled cleanup efforts were addressed in double time. Critics argued, rightly, that much of the work had progressed under Obama, and the EPA under Trump was just taking credit by finishing up the final stages of years of hard work, but the progress continued apace the next year. And, as some activists pointed out, if it was true that EPA was only wrapping up sites that had been mostly cleaned up in earlier years, what had kept the Obama administration from expediting the process and finishing the job?

Under Trump, officials deleted seven sites from the Superfund list in 2017, 22 in 2018 and 27 in 2019 — the highest single-year total since 2001. Stagnated projects like Butte, Montana's noxious Berkeley Pit have been reinvigorated and schedules have been accelerated, like at Indiana's USS Lead site, a former lead ore refinery, and the West Lake Landfill in Missouri.

And more importantly, the polluters — which are required to pick up the tab for remediation but often employ teams of lawyers to contest the fees — weren't let off the hook, either: Pruitt's EPA went after polluters quickly and with an aggression that hadn't been seen in years.

"The crazy thing that still baffles me is how far above and beyond the minimum requirement this administration has gone," says Ed Smith, who lobbied for the cleanup of the West Lake site during his time with the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, of the aggressive settlements. "You'd think this was a business-friendly administration," he said, but the EPA under Trump struck a far more aggressive cleanup agreement with the polluting parties at the West Lake Landfill than Obama's had — to the tune of an extra $150 million in remediation costs for the polluter, Smith figured. "I honestly wake up every day pinching myself. Is this real?"

For this story, I spoke with dozens of activists who agreed: The EPA under Trump has showed what it can look like when an administration gets serious about cleaning up long-neglected sites. Some of these activists are voting Republican for the first time in their lives. Some have seen their backyards and communities finally cleaned up because of the Trump administration's EPA. Worley-Jenkins said:

"I been a Democrat all my life. Trump actually gives us money to clean up these sites that have been here forever. Obama talked a lot of crap, but did very little. And people don't realize that. They want to praise him, but he didn't do nothing. He didn't do s---."The Trump administration's efforts to prioritize the Superfund site in her home town have made her a believer. She's getting into local politics and campaigned for a county magistrate slot this summer. It was a nonpartisan position, but Worley-Jenkins wasn't hiding her affiliation. "I'm running as a Republican," she said at the time.

What's behind the Trump administration's commitment to Superfund sites? There's more than a little PR savvy. Activists across the country report phone calls and home visits from high-level administration officials, the kind of appointees that generally hadn't handed their cell phone numbers to local residents. Politics is undoubtedly a part of it, too — cleaning up these sites brings in development dollars and revs up local economies, all of which could translate to a boost for Trump in 2020. Ahead of November, Andrew Wheeler, the current EPA administrator, just wrapped up a multistate tour of successful Superfund cleanups conspicuously located in battleground states, hitting sites in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Georgia.

But it's also been complicated, and the benefits have been unevenly distributed. Over the past few years, as the EPA has trumpeted its success on TV and social media, Black and Latino people have been less likely than white people to see their neighborhoods prioritized for cleanup, leading Superfund activists say. And the administration has showed, and even advertised, a preference for cleaning up development-ready sites at the expense of those in less desirable areas.

And, even more surprisingly, despite the improbable success of Superfund under Trump, the administration's commitment to cutting the EPA's budget means it may be throwing away its hardest-earned achievements.

But for activists, the strange alliance between Republican allies and Superfund activists is a story of how normal people might finally be able to force some accountability from polluting companies, and of how political will can come from the most unexpected places. Against all odds, the Superfund accomplishments of the Trump administration could be something for future administrations to learn from — as thorny and as flawed as the gains have been.

For more on this story, go here.

Comment: Politico does not often give the president more than passing credit for his leadership or humanitarian efforts. 54 Superfund sites were redeemed and Trump put corporations on the hook for cleanups that numbered 80% of the sites...that, in itself, is remarkable. Does everyone want these sites cleaned up? Yes. Has anyone else done it? No. Leading activist Lois Gibbs said: "You know the last time I saw something like this? Never." Green groups aren't about to focus on this Trump priority, neither will a Biden administration.