"During the next solar cycle, we could see cosmic ray dose rates increase by as much as 75%," says lead author Fatemeh Rahmanifard of the University of New Hampshire's Space Science Center. "This will limit the amount of time astronauts can work safely in interplanetary space."

Cosmic rays are the bane of astronauts. They come from deep space, energetic particles hurled in all directions by supernova explosions and other violent events. No amount of spacecraft shielding can stop the most energetic cosmic rays, leaving astronauts exposed whenever they leave the Earth-Moon system.

Back in the 1990s, astronauts could travel through space for as much as 1000 days before they hit NASA safety limits on radiation exposure. Not anymore. According to the new research, cosmic rays could limit trips to as little as 290 days for 45-year old male astronauts, and 204 days for females. (Men and women have different limits because of unequal dangers to reproductive organs.)

Why are cosmic rays growing stronger? Blame the sun. The sun's magnetic field wraps the entire solar system in a protective bubble, normally shielding us from cosmic rays. In recent decades, however, that shield has been growing weaker-a result of the sputtering solar cycle.

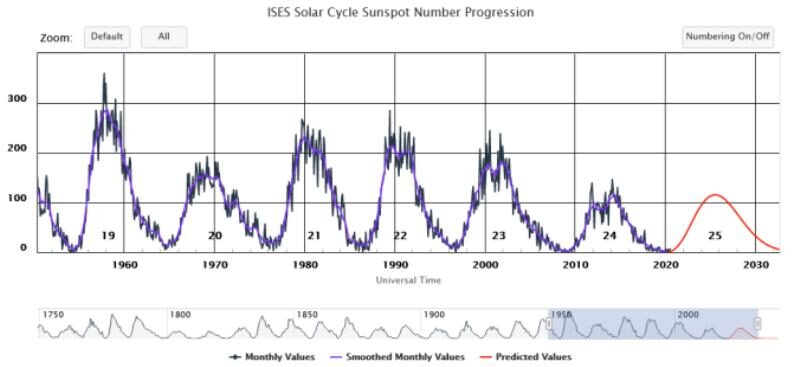

Solar activity isn't what it used to be. In the 1950s through 1990s, the sun routinely produced intense Solar Maxima with lots of sunspots and strong solar magnetic fields. Now look at the plot, above. Since the heyday of the late 20th century, the 11-year solar cycle has weakened, and the sun's magnetic field has weakened with it.

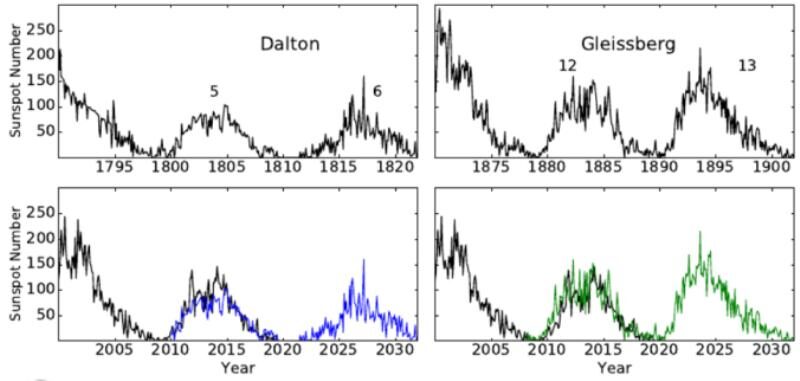

Rahmanifard and colleagues believe we could be entering a Grand Minimum-a long, slow dampening of the 11-year solar cycle, which can suppress sunspot counts for decades. The most famous example of a Grand Minimum is the Maunder Minimum of the 17th century when sunspots practically vanished for 70 years.

"We are not in a Maunder Minimum," stresses Rahmanifard. "The current situation more closely resembles the Dalton minimum of 1790-1830 or the Gleissberg minimum of 1890-1920." During those lesser Grand Minima, the solar cycle became weak, but didn't completely go away.

For years, researchers have been monitoring cosmic rays using CRaTER, a sensor orbiting the Moon on board NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO). Recent data show that cosmic rays are at very high levels-the highest since LRO was launched in 2009. (See Figure 1 in their paper.)

"We took the latest readings from CRaTER and extrapolated them forward into Solar Cycle 25 (the next solar cycle)," says Rahmanifard. "We found that radiation doses will probably exceed already-high values by 34% for a Gleissberg-like minimum to 75% for a Dalton-like minimum."

Study co-author Nathan Schwadron, also of the University of New Hampshire, wonders if NASA should rethink its safety limits to allow longer voyages. "Or," he suggests, "maybe we should wait, and only conduct long-duration missions during Solar Maximum when galactic cosmic radiation falls to lower levels."

For astronauts, it begs the question — How much can you get done in 200 days? Barring improvements in shielding technology, future space missions may be limited to only 6 or 7 months, probably too short for a Mars voyage. Lunar exploration could be safer because the body of the Moon itself blocks radiation. But in interplanetary space, the researchers caution, "the next decade or two may be more dangerous than previously realized."

Comment: See also: