He was following the line of the River Trent when he noticed an unusual feature close to the village of Swarkestone "and I thought, what's that? It looks a bit odd, and a bit round."

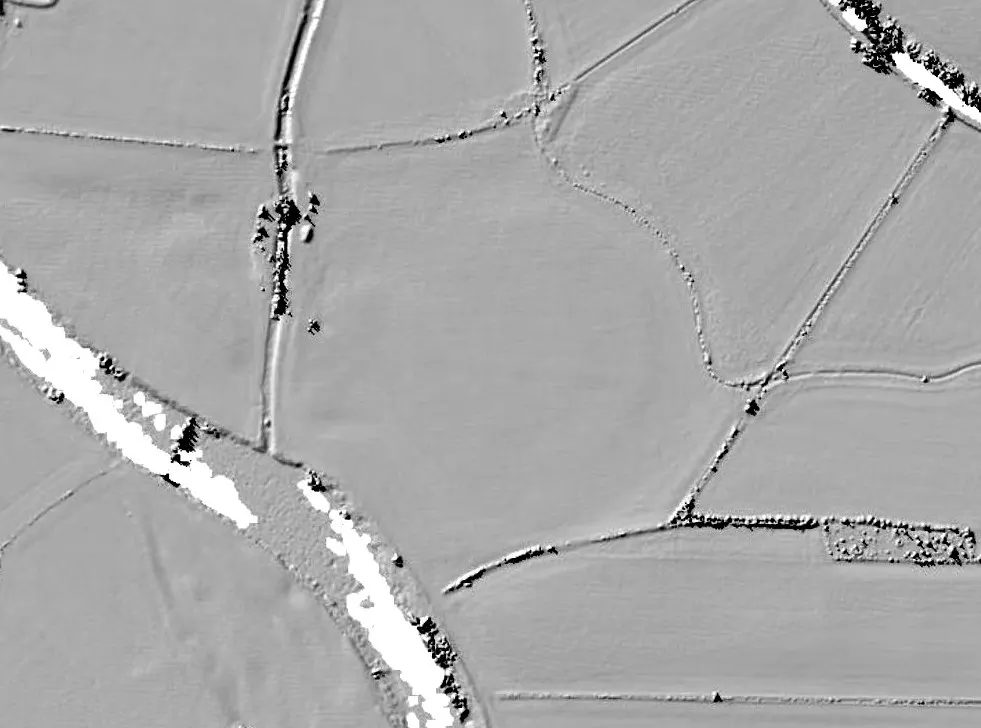

Aerial photos of the ploughed field were unremarkable, but a Lidar image - a topographical scan using laser light - showed something that maybe, just maybe, appeared to be the ghostly image of a lost henge.

A week or two later, having joined an online course run by the archaeology firm DigVentures - in part to help pass the time - Seddon uploaded his pictures to a discussion group, unsure if he had discovered a forgotten Neolithic monument, a former course of the river or a modern drainage ditch. The response from coursemates and professional archaeologists was as excited as he had hoped.

While there is no way of knowing for sure without digging, says Lisa Westcott Wilkins, managing director of DigVentures, "we are very happy to say that this does indeed look like a 'thing'".

Other known Neolithic sites nearby, the scale of the feature and the fact that historic field boundaries respect its course, all support the hypothesis, she says, that it could be a large henge - a significant find in this part of the country if so.

"Of course, we are all just itching to get out there and investigate," - just one more ambition put on hold by the current lockdown conditions.

Seddon's circular feature might be the most intriguing, but it is far from the only discovery shared by participants of the course. Developed several years ago to let students explore archaeology for the first time, or brush up on existing research, excavation and documentation skills, previous cohorts have seen about 80 participants at a time.

But with almost all of this year's excavations being shutdown because of the coronavirus crisis, the company decided to offer the course for free, and received an overwhelming response; 4,000 people from 69 countries are currently learning how to read maps, draw up plans and record finds from their own laptops.

It is far from the only online course to have seen a rush in interest since lockdown began, nor the only one focused on archaeology. The Council for British Archaeology and Lincoln University last week launched Dig School, an online programme of archaeology-themed workshops aimed at school children and families, devised by Carenza Lewis, professor for public engagement at the University of Lincoln and a former presenter of Time Team.

But while remote learning can be a challenge in any subject, acquiring practical skills such as how to handle a trowel or dig a test pit might seem a particular challenge for participants who, in many cases, are confined to flats without gardens or limited to a brief daily spin of their neighbourhoods.

Learning about archaeology online "has renewed my hope [of finding] a dig to volunteer at, despite my age," says Bonnie Stewart, a recently retired former quality manager from Asheville, North Carolina, whose lifelong passion for archaeology was sparked when she dug up a revolutionary-era stone musket ball in her back garden as a child. Living in an apartment, she has no opportunity to practise her trench-digging, so has opted for an online investigation into the area around Bath. "It was fun to find the Roman Baths and pretend that I was digging there."

Christine Green has had to temporarily close the craft shop she runs in Talgarth in the Brecon Beacons; her daughter had upcoming surgery cancelled as the crisis began, "so this is a very worrying time for both of us". Inspired by the DigVentures course, she has dug a trench a metre-deep in her back garden, in which she has found nothing more precious than a fork and a marble.

Comment: See also: