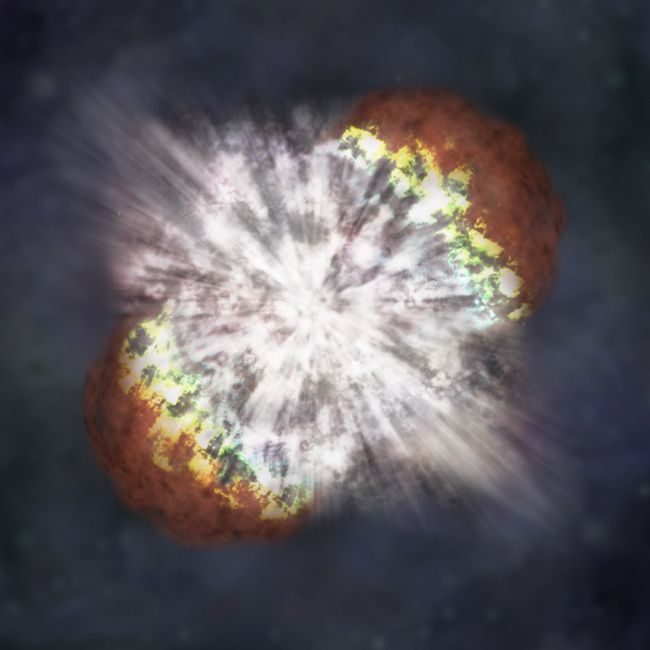

In September 2006, an exploding star 50 billion times brighter than Earth's sun blazed to life 240 million light-years away in the Perseus constellation. For 70 days, the blast grew brighter and brighter, outshining its home galaxy by tenfold and measuring hundreds of times more powerful than a typical supernova. At the time, this superbright supernova (also known as a "hypernova") was the brightest stellar explosion ever detected.

What was so special about this record-setting blast (officially labeled SN 2006gy)? Nobody knew. But now, more than a decade later, scientists may finally have a clue. In a new study published today (Jan. 23) in the journal Science, astronomers re-analyzed the mysterious emission lines radiating from the explosion about a year after it peaked.

The team discovered large amounts of iron in the emissions, which they say could only be the result of the supernova interacting with some preexisting layer of stellar material ejected hundreds of years earlier.

"A candidate scenario to explain this is [the] evolution of a binary progenitor system, in which a white dwarf spirals into a giant or supergiant companion star," the researchers wrote in the study.

Collisions among binary stars (two stars that orbit around one another) are rare, occurring once every 10,000 years or so in the Milky Way. When stars do collide, they may splash the surrounding sky with a gassy "envelope" of stellar material as the two stellar cores slowly merge.

If such a collision occurred between 10 and 200 years before the supernova was detected, the two stars could have released a gassy envelope that lingered around the system as the stars merged over the following century. When the merger finally ended in a supernova explosion, the gassy envelope could have amplified the blast's brightness to the staggering levels that astronomers saw, and also produced the appropriate iron-emission lines, the researchers wrote.

This explanation is, for now, purely mathematical, as scientists have still never seen two binary stars merging. A new clue could come in our lifetimes thanks to a nearby star system called Eta Carinae. Located about 7,500 light-years from Earth, Eta Carinae is a pair of giant stars that have been slowly exploding for a few hundred years, gradually brightening to become the most luminous star system in the Milky Way. Scientists think the stars could finally blow in their own hypernova blast sometime in the next 1,000 years, giving Earth a fireworks show like never before.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter