Jock Zonfrillo has visited hundreds of remote communities in Australia to understand the origins of ingredients and their cultural significance.

The Scottish-Italian cook, who runs the top-rated Orana restaurant in Adelaide, is this year's winner of a prize that recognizes culinary projects for their social value - in terms of education, research, health or the environment.

The Basque Culinary World Prize, with 100,000 euros (£89,000) for the winner, takes a different interpretation of the idea of a celebrity chef.

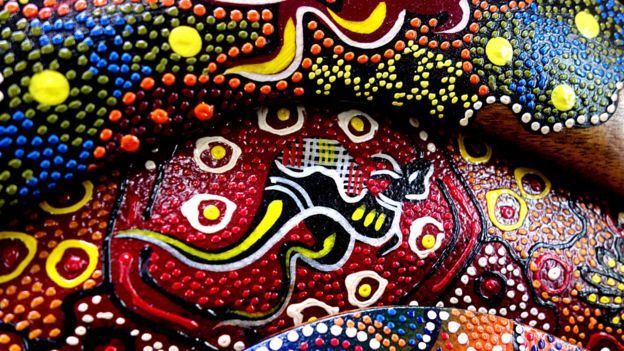

Mr. Zonfrillo's restaurant might have been rated as one of the best in the world, but this unusual gastronomic prize is for his work for the culture and rights of indigenous communities in Australia.

Cooking up change

"The First Australians are the true cooks and 'food inventors' of these lands and their exclusion from our history, and specifically our food culture, is unacceptable," he says.

"The connection to the land is something that most non-indigenous Australians cannot get their heads round, it is a very complex and spiritual connection, so there is education on both sides and that is what is so important about this project."

The rights of indigenous communities has become a politicized topic in Australia, but Mr. Zonfrillo has found food to be the best way to start difficult discussions.

"There is no question that food is a conversation starter," he says.

Kakadu and bunya

"For any country that has multiple cultures, food is an awesome way for people to acknowledge and respect each other and have an open conversation.

"I think Australian politicians are realizing that there's a gap between them and indigenous communities that needs to be closed, and food is the most practical way of closing that gap."

Mr. Zonfrillo has set up the Orana Foundation, which promotes indigenous ways of cooking and has documented more than a thousand native ingredients.

These include kakadu plums, a small fruit found in the desert which has as much vitamin C as 20 oranges; bunya nuts, which are believed to have been eaten by dinosaurs and can substitute for rice in a risotto; and karkalla, a succulent found on rugged cliffs and sand dunes which tastes like an anchovy.

Ash water recipes

"We use so many of their ingredients and techniques in the restaurant and one that is very fascinating to me is cooking with ash," he says.

"When we blanch some ingredients in ash water it removes all their bitterness and astringency, which has opened up a new list of ingredients that we had never considered as edible."

"Just last week I was in the Northern Territory and I was introduced to an edible leaf that I've never seen in my life," he says.

Mr. Zonfrillo battled heroin addiction and homelessness, before learning his trade in London under Marco Pierre White.

He moved to Australia in 2000 and intended to work in a Sydney restaurant until a chance conversation with a busker in Sydney convinced him to find out more about indigenous Australian culture.

"It's a bizarre story," he said of his unusual route to running the Orana Foundation.

"It is such a long way from home, if someone had said to me 30 years ago that I would be working with indigenous Australians running a not-for-profit I would have laughed at them, but I couldn't be happier."

Mr. Zonfrillo says countries around the world would benefit from connecting with their indigenous communities.

"In Brazil, Chile and Peru, people are really connecting with the traditional owners of the land to unlock the secrets of food that have been overlooked or forgotten," he says.

"It not only opens up a whole new pantry of ingredients but it gives us a greater connection to each other."

The culinary prize, funded by the Basque Government, is run by the Basque Culinary Centre, a higher education institution entirely dedicated to the science and art of food.

It is based in San Sebastian, a city famous for its food culture, and the prize capitalizes on the rise of the celebrity chef and their ability to influence food lovers around the world.

"When chefs started to come out from restaurants and connect with society and its challenges, we saw different initiatives starting to grow all over the world which looked at sustainability, social issues, education and health," says Joxe Mari Aizega, director general of the Basque Culinary Centre.

"So we decided to launch a prize to send the message that chefs can transform society through gastronomy and to identify the best practices by chefs."

Arantxa Tapia, the Basque minister for economic development, says that gastronomy has been a way of boosting tourism and the local economy.

The prize also aims to build on a growing interest in the origin and ethical sourcing of food.

"We want to spread the message that gastronomy is not just fine dining for a few people any more," says Mr Aizega.

"Restaurants are becoming educational places where people go to have a great experience but also discover what is behind food and its production."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter