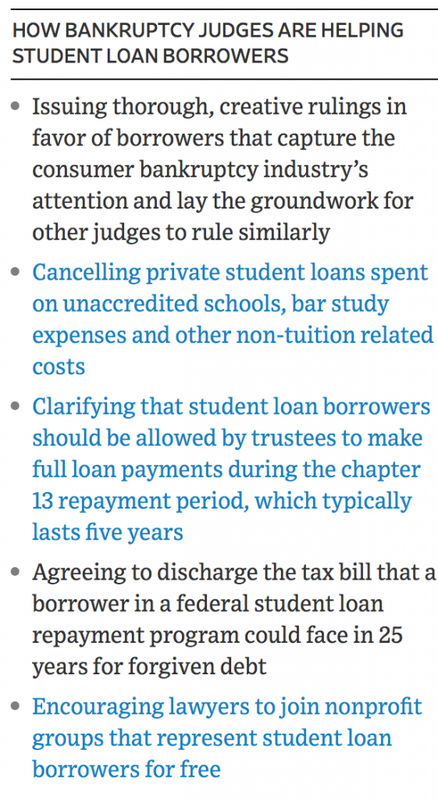

It turns out some bankruptcy judges have already concluded that the bankruptcy requirements for student loans have been excessive, and they've been allowing some borrowers to reduce or discharge their debts, something that was heretofore virtually impossible.

Mind you, this is not happening very often, in part because bankruptcy judges historically have been so unreceptive to plaintiffs weighed down by student debts seeking relief that lawyers would refuse to take these cases. As a result, last year, only 473 borrowers made the attempt.

But as the Wall Street Journal describes, some judges are of the view that the past application of the standard for whether the borrower was a candidate for relief has been too stringent. The Journal buries the legal rationale and in so doing, winds up feeding the right-wing narrative that do-gooder judges try to rewrite the law and therefore represent a menace to upstanding citizens who've had the good fortune not to need to borrow to get a degree, or if they did, never suffered a big setback, like a serious illness, job loss, or divorce.

The legal question is that in 1998, Congress restricted the discharge of federal student loans to cases where the borrower could demonstrate "undue hardship". Congress did not define what that threshold was, and The Journal's account gives the impression that the standard that came to be applied was more punitive than what "undue hardship" meant to judges when the law was revised. Indeed, it is hard not to conclude that most judges have been overzealous. From the Journal:

When Marie Brunner, a 1982 graduate of a master's program in social work, tried to cancel her loans in bankruptcy, a New York judge in 1985 said she had to show three things: she struggled financially, her struggles would continue and that she had made a good faith effort to repay. She lost.The article then points out that appeals court judges took it upon themselves to ratchet up the requirements:

That list still serves as a baseline for hardship in circuit courts that control the rules in most states.

Some appeals courts set even higher benchmarks, with one, for instance, saying borrowers must face a "certainty of hopelessness."Defenders of current harsh practices argue that the case law is well settled, and the Journal describes how one judge who pushed back against the current norms had his decision reversed on appeal:

Last year in Philadelphia, U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Eric Frank cancelled a single mother's $30,000 in student loans...Judge Frank ruled that the relevant window was five years.More and more judges are coming around to the point of view that the current standards are a misapplication of legislative intent:

An appeals court overturned his ruling, but his decision inspired Judge Mary Jo Heston in Tacoma, Wash., in December to cancel a portion of another borrower's loans.

Some of the country's bankruptcy judges are starting to argue that the prevailing legal standard is unintentionally harsh and wasn't meant for adults still on the hook for student-loan debt years after college.

Judge Frank Bailey in Boston made that argument in an April ruling wiping out $50,000 in student loans for a 39-year-old man whose health ailments prevent him from working....

Some judges, including U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Michael Kaplan in Trenton, N.J., said they are looking for ways to be more forgiving after seeing their own adult children borrow heavily for their education. Other judges grew concerned after talking to their law clerks. The typical law-school student takes out $119,000 in loans, according to the legal-education watchdog group Law School Transparency.

Two judges said they regret their rulings against borrowers more than a decade ago. One Florida judge said that if the case was filed today, the borrower would win.

Kansas judge Dale Somers said he worked particularly hard to justify the reasoning in a December 2016 ruling that cancelled more than $230,000 in interest that built up on a couple's student loans from the 1980s. They left bankruptcy owing the original amount: $78,000

Despite the signs that more and more people are starting to recognize that, as Michael Hudson puts it, "Debts that can't be paid won't be paid," there was still a depressing amount of moralizing in the Journal's comment section about how letting borrowers off the hook would encourage all sorts of profligacy

Comment: See also: