Meteotsunamis are a type of tsunami, but instead of being generated by an underwater earthquake, the source is meteorological, which gives them their unique name. Thunderstorms are the instigator for the development of many meteotsunamis because they sometimes provide the spike in wind speed and the atmospheric pressure change needed to trigger their formation.

On April 13, bands of thunderstorms pushing across northern Lake Michigan spurred the development of a pair of meteotsunamis.

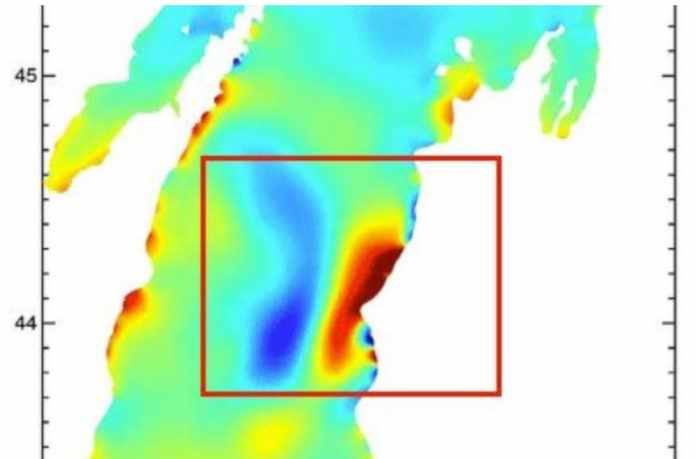

NOAA's Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) released a modeling of the meteotsunamis in a tweet Friday. Click the play button below and notice rising water level (orange/red) followed by falling water level (blue) between 43 and 45 degrees north latitude (marked on the left side of the animation).

This happens twice in the same general area of the modeled output, indicating that the two separate meteotsunamis formed in response to storms that moved through the area.

"The meteotsunami was caused by those short, extreme bursts of wind and pressure," said the GLERL.

A rapid rise of Lake Michigan's water level was noted in Ludington, Michigan, where the meteotsumani briefly submerged a breakwater.

GLERL said a gauge in Ludington reported a water level rise of 1.51 feet. It also noted that this measurement was taken in a harbor that was sheltered so the rise could have been higher in the open waters of Lake Michigan.

As shown in the tweet above, early reports indicated that another phenomenon known as a seiche led to the submerged breakwater, but GLERL confirmed that a meteotsunami was responsible.

The distinguishing factor is that meteotsunamis, like the ones from this event, last only a short time while seiches are longer lasting and impact a larger area.

Impacts from the meteotsunami were minimal, but some docks were damaged from rising and falling water levels in Manistee, Michigan.

Meteotsunamis Can Be Destructive and Deadly

Meteotsunamis are a potentially dangerous hazard on the Great Lakes that can be destructive and deadly.

Scientists explained this phenomenon in detail in February at an American Geophysical Union conference in Portland, Oregon.

"These are unusually fast changes in water level that can catch people off guard and inundate the coast, damage waterfront property, disrupt maritime activities and create strong currents," researchers said at the conference.

Thunderstorms, which generate about 80 percent of meteotsunamis, trigger their formation through a rise in wind speed and a pressure change, said Eric Anderson of NOAA's Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. This creates a wave which then moves along with the storm.

Anderson said that if the wave and storm move at the same speed, this can cause it to become larger and potentially destructive. The growth of a meteotsunami can be further intensified as it enters shallower waters.

About 100 meteotsunamis occur on the Great Lakes every year, and most are small, according to Anderson. He added that higher, destructive meteotsunamis happen about once per decade, on average.

The impacts from higher-end meteotsunamis are not nearly close to the catastrophic earthquake-induced tsunamis in Japan in 2011 and Indonesia in 2004.

Lake Michigan and Lake Erie typically have the most frequent meteotsunami activity, according to Dr. Chin Wu, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The large majority of meteotsunami events on the Great Lakes have occurred in the late-spring and summer months, when thunderstorms are most active in that region. Anderson said meteotsunami activity has historically peaked around May and June.

The most recent deadly meteotsunami occurred on the Great Lakes on July 4, 2003. The deaths of seven people in Sawyer, Michigan, were first blamed on rip currents until it was determined a meteotsunami was the cause.

Anderson mentioned that several damaging meteotsunamis have occurred since then, including in 2012, 2014 and 2017.

Meteotsunami events can happen when there is no apparent weather danger nearby. Several people were killed in a 1954 meteotsunami on Lake Michigan in Chicago four hours after the weather system triggering the event moved through.

Anderson said that once a meteotsunami is generated it can "refract or reflect off of coastlines". That may lead to the meteotsunami becoming disassociated from the weather system that led to its formation, as illustrated in the Chicago example.

Meteotsunamis are not exclusive to the Great Lakes and occur around the world.

The East Coast of the United States sees an average of about 20 meteotsunamis per year (1996-2016), according to Greg Dusek of NOAA. Those events are mostly small, he added.

A higher-end East Coast meteotsunami on June 13, 2013, generated a 6-foot wave that injured three people on a jetty in New Jersey during otherwise calm weather conditions.

Scientists hope that with additional research a forecast and warning system for meteotsunamis can eventually be developed to protect those potentially in harm's way.

Croatian scientists are working on a warning system for meteotsunami events on the Adriatic Sea, and U.S. scientists hope to build off their progress.

Comment: Meteotsunami? Ocean dramatically recedes on South American Atlantic coast as huge waves batter the Pacific side