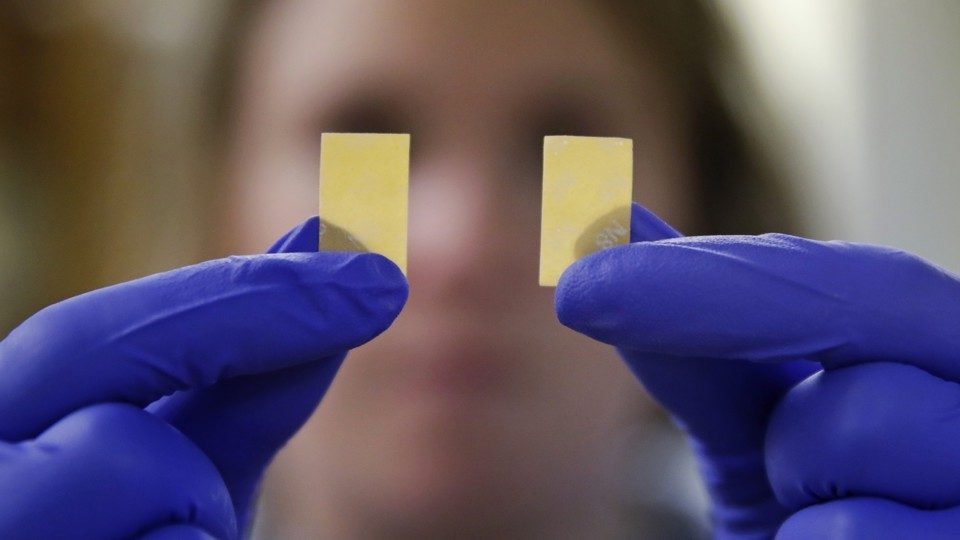

Slips of suboxone, a medication that contains buprenorphine

In the 1980s, France went through a heroin epidemic in which hundreds of thousands became addicted. Mohamed Mechmache, a community activist, described the scene in the poor

banlieues back then: "To begin with, they would disappear to shoot up. But after a bit we'd see them all over the place, in the stairwells and halls, the bike shed, up on the roof with the washing lines. We used to collect the syringes on the football pitch before starting to play," he told

The Guardian in 2014.

The rate of overdose deaths was rising 10 percent a year, yet treatment was mostly limited to counseling at special substance-abuse clinics.

In 1995, France made it so any doctor could prescribe buprenorphine without any special licensing or training. Buprenorphine, a first-line treatment for opioid addiction, is a medication that reduces cravings for opioids without becoming addictive itself.

With the change in policy, the majority of buprenorphine prescribers in France became primary-care doctors, rather than addiction specialists or psychiatrists. Suddenly, about 10 times as many addicted patients began receiving medication-assisted treatment, and half the country's heroin users were being treated. Within four years, overdose deaths had declined by 79 percent.

Of course, France has a socialized medical system in which many users don't have to worry about cost, and the country also developed a syringe-exchange program around the same time. Some of the users did sell or inject the buprenorphine (as opposed to taking it orally, as indicated), though these practices didn't result in nearly as many deaths as heroin does.

"It seems that the French model raises questions about the value of tight regulations imposed by many countries throughout the world,"

wrote the author of a study on the phenomenon, the French psychiatrist Marc Auriacombe, in 2004.

Just what are these regulations? In the United States, doctors must take a special, eight-hour class to get a waiver that allows them to prescribe buprenorphine. The classes can cost money and force even more tasks into doctors' already packed schedules. In

one study, 10 percent of doctors said they didn't even know how to get the waiver. According to Andrew Kolodny, a psychiatrist who studies addiction at Brandeis University, some primary-care doctors might frankly be daunted by the prospect of working with addicted patients-a sentiment that's

also reflected in physician surveys. Meanwhile, there is no special training class required to prescribe prescription painkillers, Kolodny points out. (There's also a cap on how many buprenorphine patients a single doctor can have, though Congress is considering

waiving this limit through new legislation.)

There are multiple other issues in the American health-care system that make accessing buprenorphine difficult for addicted people. Medicaid pays for a

substantial chunk of all drug-abuse treatment, but state Medicaid programs

impose limits on when and how they'll cover buprenorphine.

Finally, doctors

know that if they sign up to prescribe buprenorphine, all the local heroin users will flock to them, potentially crowding out their other patients, says Stanford University professor of psychiatry Keith Humphreys. "Doctors also want to take care of kids with colds, and adults with bad backs and cancer patients and the panoply of humanity that they know how to take care of," he said via email. One way to resolve this would be to require doctors who are licensed to prescribe prescription painkillers to also prescribe buprenorphine.

The result of all this is that many addicted people just can't find a doctor willing to prescribe them buprenorphine on demand, especially if they want insurance to pay for it. For example,

The Atlantic looked up Parkersburg, a city of 30,000 people in West Virginia, the state with the

most overdose deaths, on

Suboxone.com, a site that lists buprenorphine providers. We found 10 doctors within a 50-mile radius who prescribe buprenorphine, and we attempted to reach all 10.

Some of the contacts appeared to be in the same office. We were told one doctor had a waiting list for patients, three doctors did not accept insurance and charged hundreds of dollars a month in cash, one had a number that was disconnected, and, finally, one was both accepting new buprenorphine patients and took insurance.

"

If you really want someone who's addicted to seek treatment, you have to have it be less expensive than using heroin," Kolodny said. For many addicted Americans, that's not currently the case.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter