The principal cause for the North Atlantic right whale's precipitous decline has been the use of increasingly heavy commercial fishing gear dropped on to the sea bed to catch lobsters, snow crabs and hogfish off the east coast of North America. Whales swim into the rope lines attached to these sea-bed traps and their buoys and become entangled. In some cases hundreds of metres of heavy rope, tied to traps weighing more than 60kg, have been found wrapped around whales. "We have records of animals carrying these huge loads - which they cannot shake off - for months and months," said Julie van der Hoop, of Aarhus University in Denmark.

"In some cases they have to burn more than 25,000 calories a day to carry these great weights around with them. Some whales die. In other cases, divers have been able to free them but the whales are often left very thin and undernourished. As a result, they cannot reproduce."

The North Atlantic right whale, Eubalaena glacialis, derives its name from the fact that early whalers considered them to be the "right" whales to hunt - they are slow swimmers, linger in coastal waters and float after being killed. Vast numbers were slaughtered across the Atlantic, with only a few pods surviving along the east coast of the United States and Canada. Numbers dropped - possibly to a population as low as 100 - until in 1935 it was declared illegal to hunt them.

For the rest of the 20th century their numbers increased, although at a very slow rate. By 2000 it was thought that there were about 400 right whales in the North Atlantic. This still left the species endangered but it was hoped that a continued rise in numbers would eventually take them out of danger of extinction.

However, figures presented at a meeting of the Society of Marine Mammalogy held in Halifax, Canada, last month have dashed those hopes. Delegates heard that about 50 right whales a year were now becoming trapped in fishing gear and that death rates due to entanglement have more than doubled over the past 10 years.

"This year turns out to have been catastrophic for right whale losses," said Ann Pabst, of the University of North Carolina in Wilmington. "We know of at least 16 right whales that were killed from entanglement, and there could be more that we haven't found about yet."

An example of the tribulations suffered by right whales is provided by the story of Ruffian, a 13-year-old male who was discovered entangled in 138 metres of rope and a 61kg snow crab trap, which he had dragged from Canada to Florida over a period of several months. He was eventually freed by divers from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. "I am surprised Ruffian survived given the calories he had lost in dragging around that weight," said van der Hoop.

Other right whales have not been so lucky and many have died. In other cases, females have been left dangerously undernourished and unable to reproduce. This last point is stressed by van der Hoop. "The problem facing the North Atlantic right whale is not just one of losses of lives but of a general loss of fertility."

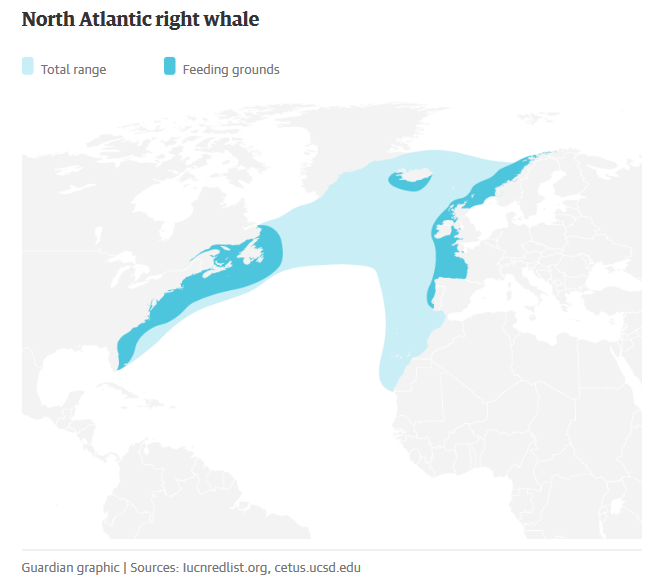

In addition to entanglements, marine biologists also point to the growing problem of ship strikes. Right whales are large, growing up to 50ft in length, and slow moving - making them vulnerable to being hit. In 2008 regulations were introduced requiring large vessels to slow down as they entered ports at certain times in key areas: in winter in the south, where females were calving, and in summer in the north, when right whales are in their feeding grounds. In other cases, shipping lanes were moved.

"However, right whales now seem to be moving out of their historical grounds - most probably in their search for food," said Bill McLellan, also of the University of North Carolina in Wilmington. Right whales feed on small crustaceans called copepods and some researchers believe that these are moving in response to ocean temperature changes triggered by global warming. "The whales may be following the copepods and that is taking them into waters where they are more likely to be struck by ships," said McLellan.

More research to understand these population shifts is now needed urgently, say some scientists. In addition, work led by Amy Knowlton of the New England Aquarium, suggests that the recent strengthening of rope nets and lines has been unnecessary and a return to weaker ropes would save right whale lives. An even better solution, although some way off, would be the development of an electronic means of trapping fish that would eliminate the need for rope lines completely. "There needs to be a paradigm shift in the fishing industry," Knowlton states in a recent issue of Science.

All agree that action is needed. "Any large mammal whose population is down to the low numbers we are finding is in real trouble," said Pabst. "So extinction is a very real potential outcome."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter