Stents are commonly used for stable chest pain - but the devices may not be helping.

There's an epidemic of unnecessary medical treatments, as David Epstein of ProPublica recently documented in a terrific investigation: Doctors routinely perform procedures that aren't based on high-quality research, or even in spite of evidence that contradicts their use.

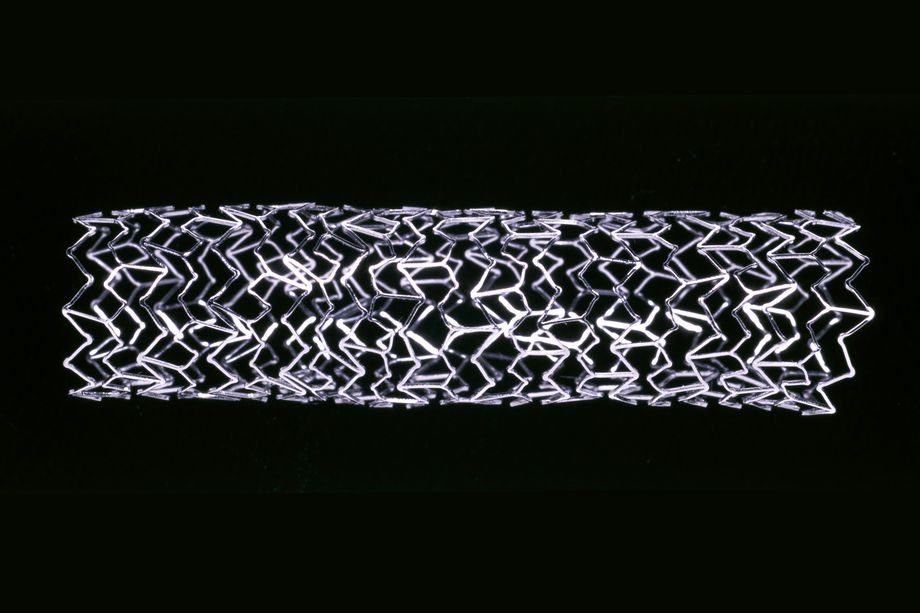

One of the prime examples of a dubious treatment that Epstein and others have pointed to is cardiologists putting little mesh tubes called stents in patients with stable angina - chest pain caused by clogged coronary arteries that arises only with physical exertion or emotional stress.

Doctors insert the devices into narrowed or blocked arteries to pop them open, helping blood flow to the heart again. The idea is that stents should help soothe the suffering of patients with angina (or chest pain) and drive down the risk of a heart attack and death in the future.

But studies show that stable angina can be well controlled with medication. And researchers have found that stenting chest pain patients doesn't help them live longer or reduce their risk of disease - in fact, heart attacks and strokes can be potentially deadly side effects of stent procedures. There's also been a lingering question about whether stents truly work to relieve pain.

Now, researchers from the United Kingdom have published a high-quality study in the Lancet that helps answer the pain question. Building on years of lower-quality evidence, the well-designed study suggests stents may in fact be useless for pain in people with stable angina who are being treated with medication.

"Surprisingly, even though the stents improved blood supply, they didn't provide more relief of symptoms compared to drug treatments, at least in this patient group," said Rasha Al-Lamee, lead author of the study and a researcher at the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London, in a statement. This doesn't mean stents should never be used in stable chest pain patients - some patients can't take the medications that control angina, for example - but doctors may want to consider inserting these devices as a last resort.

Considering 500,000 patients get stents for stable angina each year in the US and Europe alone, and the devices can cost up to $67,000, depending on the hospital and a patient's insurance coverage, the Lancet paper is poised to shake up cardiology, as the New York Times reported.

The trial is also important for another big reason: It raises critical questions about the quality of evidence doctors rely on to make life-and-death decisions for their patients.

The controversy over stents for patients with stable chest pain

Over the years, studies have been piling up that suggest stenting stable angina patients may not actually be all that helpful.

A decade ago, researchers published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine showing that stents did not improve patients' mortality risk or cardiovascular disease outcomes. Since then, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials on stents in stable angina patients have similarly found the devices don't outperform more conservative medical therapies (such as medication) when it comes to preventing heart attacks or extending patients' life expectancy in the long term.

There was still a question about using stents in stable patients, whether the devices could relieve chest pain in the shorter term. Data from low-quality studies suggested this was possible.

The only way to resolve the question would be to perform a double-blind "sham control" study of stents: giving half of the patients a fake stent and the other half a real stent, with both doctors and patients unaware of (or "blinded" to) which procedure they were involved with. Since we know medical procedures can produce a strong placebo effect, this kind of study could tease out whether it was the stent that was reducing patients' pain or a placebo effect produced by the operation.

But no one had ever done a double-blind sham-control study - the gold standard of evidence for medical device studies - on stents in stable chest pain patients, until this new Lancet paper.

How researchers used a fake operation to test whether stenting works

The authors of the Lancet paper enrolled 230 patients with stable angina and at least one narrowed coronary vessel. For six weeks, they made sure the patients were getting the best medical treatment for angina, like beta blockers or long-acting nitroglycerine.

What came next rarely happens in medical device trials (and it's why cardiologists are applauding this study): They gave half the patients a sham stent. So after the six-week startup phase, where patients were stabilized with medications, 195 of them were randomly assigned to get either a stent in their clogged artery or a sham stent procedure. The study was double-blinded - again, the patients and doctors didn't know which procedure they were involved in - to reduce the risk of bias.

The doctors then followed up with their patients after another six weeks. The main outcome they were interested in was how much time each group could spend exercising on a treadmill, since angina often acts up with exertion. (They also looked at other secondary endpoints, such as changes in oxygen uptake and the severity of chest pain.) By the end of the study, the researchers found there were no clinically important differences between the real stent group and the sham stent group.

So actual stents didn't outperform the placebo stents. "It's just like a sugar pill," said University of California San Francisco cardiologist Rita Redberg. "We know sugar pills make a lot of people feel better - though sugar procedures make even more people feel even better."

Here's the most disturbing part: One in 50 stent patients will experience serious complications - such as a heart attack, stroke, bleeding, or even death. So these devices don't come without risks, and this Lancet paper again suggests they may not be helping patients.

"This should make us take a step back and ask questions about what we are accomplishing for this procedure," said Yale cardiologist Harlan Krumholz.

David Brown, a Washington University School of Medicine cardiologist who has been studying the effects of stents for a decade, said he wasn't surprised by the findings.

"[Stenting stable patients] is based on a simplistic 20th-century conceptualization of the disease," he said. "It's like the artery is a clogged pipe and if you relieve those blockages, the water will flow freely." But this study suggests most patients' pain symptoms may actually be coming from disease in their smaller blood vessels, not from blockages in the large coronary vessels that are always the targets for stents, he added.

In an editorial that accompanied the Lancet paper, Brown and Redberg wrote that medical guidelines need to change so that stenting for stable angina is only recommended as a last resort. "Patients should also be told that sham controlled trials don't show any benefit," Brown added.

This study speaks to a much bigger problem with medical evidence

The study represents the best available evidence on the impact of stenting for pain in stable angina patients - and could eventually avert unnecessary, costly procedures in the future. But the study is also important for what it says about the quality of medical evidence doctors often rely on to make decisions.

"This is a great example of a device that got on the market without ever having a high-quality trial behind it," Redberg says. "For 40 years, we have been doing this procedure without any evidence that it's better than a sham procedure."

Right now, medical devices are less rigorously regulated than drugs: Only 1 percent of medical devices get FDA approval with high-quality clinical trials behind them. Even in these cases, devices typically reach the market based on data from a single small, short-term trial, Redberg wrote in a 2014 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, where she called for a sham control study of stents.

The new Lancet study demonstrates why this kind of investigation is so critical in medicine. "The results of ORBITA show (once again) why regulatory agencies, the medical profession, and the public must demand high-quality studies before the approval and adoption of new therapies," Redberg and Brown wrote in their recent editorial. Right now this isn't happening. And stents surely aren't the only device patients may be getting that are more placebo than proven, and have potentially deadly side effects.

Comment: For more on the dubious safety of medical devices, see: Vagus Nerve Stimulator by Cyberonics: A Telling Anecdote about Regulatory Capture and Medical Device Safety