Fossils from a 374-million-year-old tree found in north-west China have revealed an interconnected web of woody strands within the trunk of the tree that is much more intricate than that of the trees we see around us today.

The strands, known as xylem, are responsible for conducting water from a tree's roots to its branches and leaves. In the most familiar trees the xylem forms a single cylinder to which new growth is added in rings year by year just under the bark. In other trees, notably palms, xylem is formed in strands embedded in softer tissues throughout the trunk.

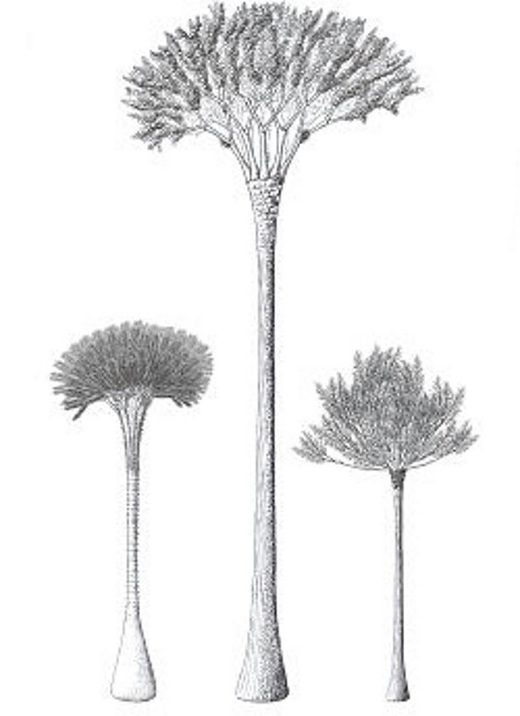

Writing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the scientists have shown that the earliest trees, belonging to a group known as the cladoxlopsids, had their xylem dispersed in strands in the outer 5 cm of the tree trunk only, whilst the middle of the trunk was completely hollow.

The team, which includes researchers from Cardiff University, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, and State University of New York, also show that the development of these strands allowed the tree's overall growth.

Rather than the tree laying down one growth ring under the bark every year, each of the hundreds of individual strands were growing their own rings, like a large collection of mini trees.

As the strands got bigger, and the volume of soft tissues between the strands increased, the diameter of the tree trunk expanded. The new discovery shows conclusively that the connections between each of the strands would split apart in a curiously controlled and self-repairing way to accommodate the growth.

At the very bottom of the tree there was also a peculiar mechanism at play -- as the tree's diameter expanded the woody strands rolled out from the side of the trunk at the base of the tree, forming the characteristic flat base and bulbous shape synonymous with the cladoxylopsids.

Co-author of the study Dr Chris Berry, from Cardiff University's School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, said: "There is no other tree that I know of in the history of Earth that has ever done anything as complicated as this. The tree simultaneously ripped its skeleton apart and collapsed under its own weight while staying alive and growing upwards and outwards to become the dominant plant of its day.

"By studying these extremely rare fossils, we've gained an unprecedented insight into the anatomy of our earliest trees and the complex growth mechanisms that they employed.

"This raises a provoking question: why are the very oldest trees the most complicated?"

Dr Berry has been studying cladoxylopsids for nearly 30 years, uncovering fragmentary fossils from all over the world. He's previously helped uncovered a previously mythical fossil forest in Gilboa, New York, where cladoxylopsid trees grew over 385 million years ago.

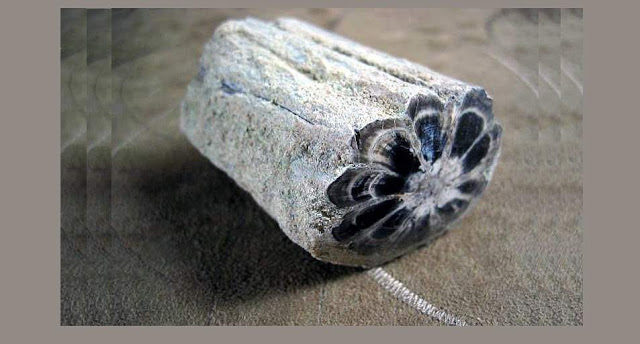

Yet Dr Berry was amazed when a colleague uncovered a massive, well-preserved fossil of a cladoxylopsid tree trunk in Xinjiang, north-west China.

"Previous examples of these trees have filled with sand when fossilised, offering only tantalising clues about their anatomy. The fossilised trunk obtained from Xinjiang was huge and perfectly preserved in glassy silica as a result of volcanic sediments, allowing us to observe every single cell of the plant," Dr Berry continued.

The overall aim of Dr Berry's research is to understand how much carbon these trees were capable of capturing from the atmosphere and how this effected Earth's climate.

The above story is based on Materials provided by Cardiff University.

Reader Comments

Forgive my comment from out of nowhere but I've been reading Velikovsky and Sitchin...

Which means, there really could be something to what Velikovsky wrote...but his staid and paid establishment 'peers' made sure to belittle him and his views and deny any funding of science that could even potentially raise questions about the status quo.