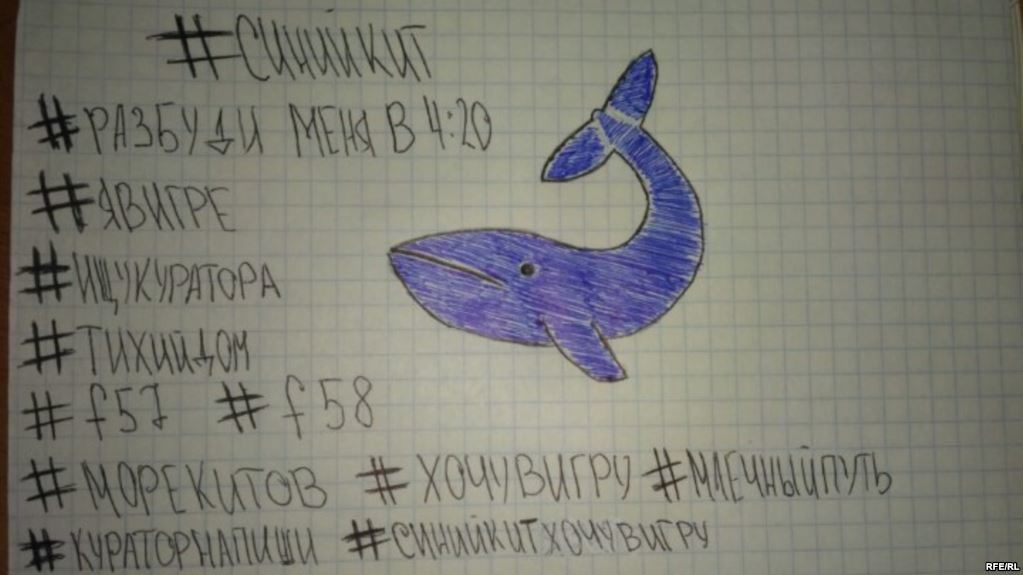

Across Russia and the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, alarming Blue Whale headlines have become a nearly daily occurrence: a child or teen being encouraged to commit suicide through participation in a ghoulish online "game" driven by Russian-language hashtags including "blue whale," "sea of whales," "I'm in the game," "Wake me at 4:20," "F58," and many others.

According to a new Novaya Gazeta report, the Russian Public Internet-Technology Center tracked 4,000 uses of the game hashtags on January 20 alone. Suspicious cases have also been reported in other post-Soviet states Ukraine, Belarus, and Azerbaijan.

But while the Russian-language Internet is groaning with profiles of young people playing or seeking to play the game, shocking photographs of self-injury like cutting marked with the game's hashtags, and purported links to teen suicides, not a single death in Russia or Central Asia has been definitively tied to Blue Whale.

For instance, on February 6, a 19-year-old resident of Karaganda, Kazakhstan, committed suicide by hanging in an incident that was widely attributed to the influence of a Blue Whale group. However, the victim's uncle, Marat Aitkazin, told RFE/RL there was no connection between the tragedy and any Internet games.

Mental-health professionals and government officials are expressing concern, although for different reasons. Activists are urging a focus on the factors that drive youths to be interested in such ghoulish games, while politicians tend to see the Blue Whale phenomenon as an argument for bolstering control over the Internet.

At a hearing on February 16 of Russia's Public Chamber to discuss proposed legislation increasing punishments for inciting suicide, members heard allegations that Blue Whale had been created by "Ukrainian nationalists" as "a professionally prepared campaign that has caught up at least 2 million youths," according to a report of the meeting in the daily Kommersant.

Media in Russia's North Ossetia region reported on February 17 that four local people, including two minors, had been detained on suspicion of organizing a Blue Whale group that "might" have played a role in the February 1 suicide of a 15-year-old in Sindzikai.

On February 20, prosecutors in Altai opened an investigation into suspicion that an unidentified Blue Whale-type group unsuccessfully pressured a 15-year-old boy to commit suicide over a period of three months.

Are You Ready?

"I want to play the game," an RFE/RL correspondent wrote after creating a fake profile for a 15-year-old girl on the popular Russian social-media site VKontakte.

"Are you sure? There is no way back," responded a so-called curator of the Blue Whale game.

"Yes. What does that mean -- no way back?"

"You can't leave the game once you begin."

"I'm ready." Then the curator explained the rules.

"You carry out each task diligently, and no one must know about it. When you finish a task, you send me a photo. And at the end of the game, you die. Are you ready?"

"And if I want to get out?"

"I have all your information. They will come after you."

The first task assigned to RFE/RL's imaginary Internet user is to scratch the symbol "F58" into her arm. A photoshopped image was sent, but the curator stopped responding.

Over the course of about a week, RFE/RL managed to contact more than a dozen self-proclaimed current and former players and several curators.

"I am your personal whale," another curator wrote, explaining that the game consisted of 50 tasks spread over 50 days. "I will help you take the game all the way to the end. The last day is the end of the game. If you die, you win. If you don't, we will help you. Are you ready?"

The curator then promised to send the first task at 4:20 a.m. But by then, the curator's account had been blocked.

'Group Of Death'

Over the last six months or so, dozens of suicides and attempted suicides in Russia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan have been provisionally linked to the game, although on closer inspection none of them has been found to have a conclusive tie.

On November 14, 2016, police outside of Moscow arrested 21-year-old Filipp Budeikin on suspicion of being an organizer of a Blue Whale "death group," as the press has taken to calling the game. Media reports said at the time that 10 other people from various regions were detained around the same time, but all of them were questioned only as "witnesses" and released.

Authorities said Budeikin was suspected of complicity in 15 suicides. However, Budeikin's lawyer, Rostislav Gubenko, told RFE/RL that only one case was still under investigation. A court has authorized police to hold Budeikin until May 15.

"I think they just rushed things," Gubenko said. "There was an article in the newspaper, a bit of a scandal, pressure to do something. They thought evidence against [Budeikin] would come out, but there has been nothing."

Concern about the game was piqued by a much-criticized article in Novaya Gazeta in May that claimed, among other things and seemingly without justification, that the "vast majority" of the roughly 130 youth suicides in Russia between November 2015 and April 2016 were tied to the Blue Whale phenomenon. The paper published an equally alarming follow-up article on February 16.

Such panics occur fairly regularly all over the world. In 2007, The Independent reported that "at least 16 young people in the U.K." had committed suicide after visiting "pro-suicide websites and chat rooms." Even in the pre-Internet era of the 1980s, the popular role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons prompted a mass moral panic amid rumors of murders, suicide, and satanic rituals.

So authorities are clearly concerned. In Russia, conservative Federation Council member Yelena Mizulina has asked prosecutors to investigate reported connections between the Internet groups and any suicides. She argued that the Blue Whale phenomenon had not slowed noticeably since Budeikin's arrest.

Duma Deputy Irina Yarovaya has promised to introduce legislation criminalizing efforts to entice or intimidate minors into committing suicide. Chechen Republic head Ramzan Kadyrov has publicly warned about the Blue Whale phenomenon, while Ingushetia head Yunus-Bek Yevkurov recently said the authorities "need to be ready" to cope with the issue, although he acknowledged there had been no Blue Whale cases in Ingushetia.

In Central Asia, Kazakh Interior Minister Kalmukhanbet Kasymov has called for creating a national database of social-media users. In the Kyrgyz capital, Bishkek, police have combed through schools and Internet cafes checking children for signs of cutting or for suspicious messages on their phones.

In all three countries, there have been calls for blocking websites and other similar measures. Burul Makenbaeva, director of the NGO Mental Health and Society in Bishkek, told Eurasianet that activists feared the Blue Whale anxiety could become an excuse to "clamp down on social networks."

Citizen activists have also taken up the cause. In Russia, an Omsk-based organization called Civic Patrol claims it is monitoring social media and reporting concerns to the government. When the RFE/RL correspondent created an account to investigate the game, it was deluged with messages from so-called dolphins, urging the make-believe 15-year-old to avoid the game and seek help. Many of the "dolphins" were posing as curators in an apparent effort to dissuade players from harming themselves.

When the fake account was used to communicate with people playing the game or curators, conversations frequently came to a halt as those pages were blocked.

Site administrators have been aggressively blocking the game hashtags almost as quickly as they emerge, as RFE/RL learned during its investigation.

'If They Feel Completely Alone'

Child suicide is a real problem in these countries. According to the Russian government, 720 minors committed suicide in 2016. Authorities say the main causes are unrequited love, family problems, and mental-health issues. Lack of opportunity and widespread alcoholism and drug abuse are cited as contributing factors. Only 0.6 percent have any connection to the Internet or social media.

Officials in Kyrgyzstan told RFE/RL that 15 minors committed suicide in January alone, nearly double the figure for January 2016. "The reasons are bad relations within the family and various life circumstances," Interior Ministry spokesman Bakyt Seitov said.

For this reason, psychologists and social workers say there are real reasons to be concerned about Blue Whale groups and urge parents to be vigilant if they see their children manifesting interest in morbid games.

Aleksandr Kolmanovsky is a Moscow psychologist who says the parents of two girls caught up in the game have sought him out in the last few months, as well as the administrator of an orphanage where several wards were playing.

Natalya Lebedeva, head of an online consulting project called Your Territory Online, says her organization regularly provides consulting to teens who are playing or who are concerned about their friends.

"When a child gets into this game, he is not immediately asked to commit suicide," Lebedeva says. "But the tasks are such that they drive children into a state of helplessness and create an oppressive atmosphere. And when we are talking about children who already have some particular problems, these tasks can make their situation worse and increase their risk of suicide."

Lebedeva says her group conducted 1,400 consultations in January, about 20 of which involved minors with suicidal thoughts.

Psychologist Marina Slinkova agrees that Blue Whale-type games are a concern, but they don't lead children to suicide on their own. "I don't think that the only dark spot in the life of such a child is the Internet," she tells RFE/RL. "If everything is OK in his life but he suddenly gets involved with these groups, I don't think they can take over his mind to such an extent."

"But if they have no one to talk to, if they feel completely alone, such youths can find some sort of support there."

In The Real World?

Many participants in the Blue Whale game say they are threatened by curators when they try to leave the game. One participant received a message saying, "Your mother won't reach the bus stop tomorrow" -- which frightened her because her mother actually does commute to work by bus.

A player who identified himself as Ivan tried to quit the game by blocking his curator. But he received a message from another account saying, "You can't hide from us." However, he blocked that account as well and the matter ended there.

Many Blue Whale players are convinced -- wrongly -- that curators have access to a program that lets them convert the players' Internet-protocol (IP) address into a geographical location. However, there are no reported incidents of any Blue Whale incidents occurring in the nonvirtual world.

In the course of its investigation, RFE/RL chatted online with more than a dozen Blue Whale participants, none of whom had advanced very far in the game. They described typical tasks as drawing a whale on one's body or on paper, cutting a vein, or carving a whale or other symbol on one's arm. Many said they found appropriate photographs on the Internet or created them with graphics tools.

Several of the players complained of "false" curators. Stefan, a 15-year-old from Solikamsk, in Russia, says three different curators gave him as his second task the assignment of sending them 200 rubles ($3.50). He didn't have any money, so he blocked them.

The majority of players told RFE/RL they got involved either to "mess with the curators" or just because "it seemed interesting." A few gave darker responses.

"Do you want to die?" the RFE/RL correspondent asked one girl. "Yes," she answered.

But before the conversation could continue, her account was blocked.

Robert Coalson contributed to this report. With reporting from RFE/RL's Kyrgyz and Kazakh services, as well as Current Time TV

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter