"The most important thing that can come out of these fragments is if we can connect them with other documents that were looted from the Judean Desert, and that have no known provenance," says Dr. Uri Davidovich of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, among the scientists investigating the caves.

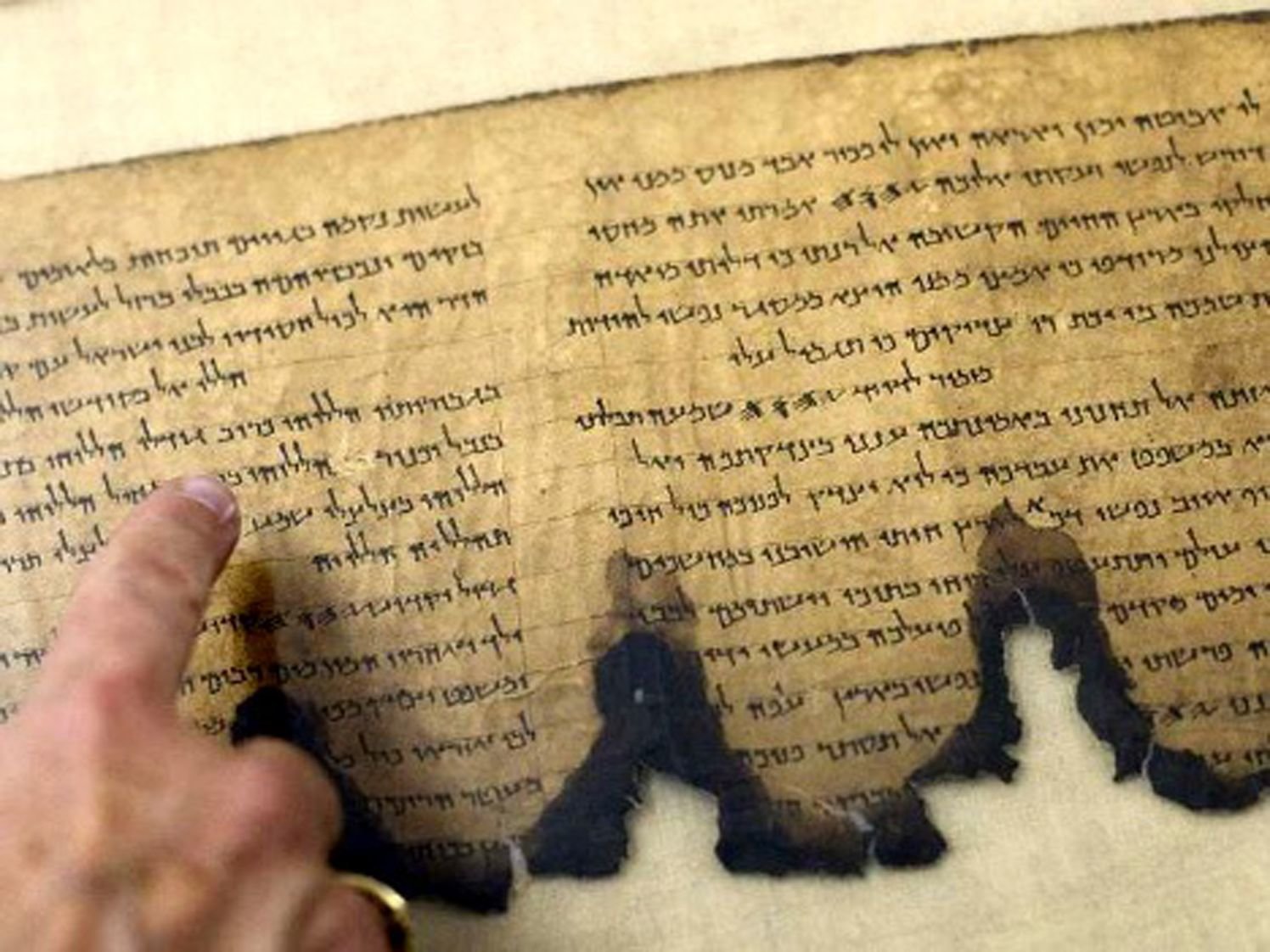

In 1947, a Bedouin shepherd tossing a stone into a cave in the vicinity of Qumran heard the sound of an earthenware jar cracking, which led to what some have called the greatest archaeological discovery of the 20th century. Upon crawling inside, he found the first of what came to be known as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Cave of the Skulls, named for seven human skulls and other skeletal remains, discovered by Prof. Yohanan Aharoni in 1960, is part of the Large Cave Complex, a series of naturally occurring spaces atop a steep cliff on the northern bank of Tze'elim Stream, in the southern part of the desert. The site is in one of the starkest areas of the Judean Desert.

The complex also includes the Cave of the Arrows, where the extraordinarily arid conditions preserved a dozen 30-inch-long reed arrow shafts for approximately 1,800 years, as well as iron arrowheads; and the Cave of the Scrolls where the earliest known documents from the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt were unearthed by archaeologists.

Lice combs and papyri

The latest finds, two papyri fragments about two by two centimeters with writing and several fragments without discernible letters, were made during a three-week salvage excavation in the Cave of the Skulls this May and June by a joint expedition of the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The excavations were led by Uri Davidovich and Roi Porat of the Hebrew University, together with Amir Ganor and Eitan Klein from the IAA.

Though the finds so far are small and many are from secondary dumps associated with modern looting of the caves, the excavations shed new light on human activities in the Judean Desert cliff caves. Despite the inhospitable conditions, they were occupied on and off for thousands of years, starting in prehistoric times and through the Roman period.

Hundreds of fragments of leather, ropes, textiles, wooden objects and bone tools were discovered inside the cave thanks to the aridity of the Judean desert, which preserved the organic material.

Some things evidently never change, and one is pests. One of the more relatable finds in the cave was pieces of wooden lice combs from the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Along with the unique artifacts made of organic materials, dozens of pottery shards, stone vessels and flint items were discovered inside the cave. Several metal objects were found as well, including needles and cosmetic tolls as well as hollow-headed hobnails for sandals.

Another interesting discovery was a bundle - textile wrapping a cluster of beads, which was found in a natural niche at the edge of the cave's western wing. This bundle has yet to be opened but has meanwhile been X-rayed to identify its content. Joining two other bundles of beads Aharoni had previously discovered, this is the largest collection of beads ever discovered in the Levant from the Chalcolithic period, a prehistoric time predating the Copper Age.

Housing for herders?

Even so, thousands of remains from foodstuffs including wheat and barley, palm dates, olives and pomegranates support the archaeologists' long-held contention that these caves were used by refugees during the Roman and Chalcolithic times. They were certainly used by the Jewish warriors and rebels to hide from the approaching Roman armies over 2,000 years ago, say the excavation directors.

What use these caves had in earlier Chalcolithic times is a matter for speculation. Suggestions range from seasonal living spaces for herders or traders, to places of refuge related to social tensions within the settled communities located west of the Judean Desert.

Davidovich thinks the second explanation is more likely. "These caves are very difficult to access, and they were used in their natural forms without changes or modifications that would make them more convenient for prolonged occupation," he points out. "This does not make sense when you think of ephemeral stays by shepherds or the like, but is much more plausible when you consider that they served as temporary refuge places."

The renewed excavations in the Cave of the Skulls is just the first step in a new project of the IAA and the Hebrew University to continue exploring the Judean Desert caves, to salvage hidden treasures that might still lay in the caves, at least before robbers get there first. "We have all the reasons to believe that there are still scrolls hidden," Davidovich says. "Several documents from the Roman times and even from the Iron Age have surfaced in recent years in the antiquities market. They must have originated in the Judean Desert caves."

Anything of real value to us,the human race-

Will be promptly concealed from us by those who proclaim themselves superior beings.