At 9.15am on Friday morning, a minute's silence was held to remember Aberfan.

Here, Jamie Bowman gets Ted McKay's view of the shocking incident half a century ago...

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the Aberfan Disaster.

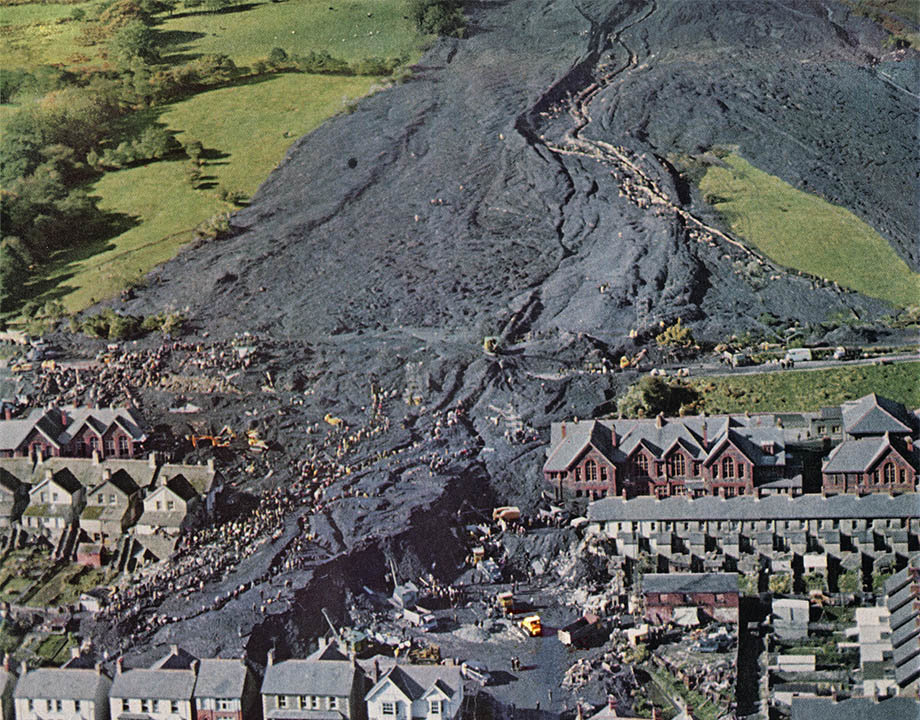

It started as a normal school day at Pant-glas Junior School but in the five minutes between 9.15 and 9.20 am, tragedy struck when thousands of tons of coal waste burst down the mountainside and engulfed the school.

The tragedy claimed 144 lives, including 116 schoolchildren.

It was a hearbreaking day that everyone alive that day will remember.

Former National Union of Mineworkers secretary for North Wales Ted McKay says it was a disaster that shouldn't have happened.

"We were all shocked and we all donated money towards the pit," says Ted, from his home in Gwersyllt.

"Those poor children - they couldn't recognise them - they were black. One poor child was only recognised by the football cards he had in his pocket.

"It was tantamount to murder really."

More than 40,000 cubic metres of slag covered the village in minutes.

The classrooms at Pantglas Junior School were immediately inundated; young children and teachers died from impact or suffocation.

Many noted the poignancy of the situation.

If the slag heap had slipped an hour earlier - before the school opened - the children would not have been in their classrooms.

And if it had struck a few hours later, the school would have broken up for half-term.

Parliament quickly passed new legislation about public safety in relation to mines and quarries.

For 82-year-old Ted, it was the earlier example set by his close friend and future Wrexham MP Tom Ellis, when he was in charge of Bersham Colliery near Rhostyllen, that should have been heeded.

"Tom was a character and he was ahead of the game," says Ted.

He wanted to do something for the village because the tip was so unsightly.

Bersham Colliery closed in 1986 with the loss of 300 jobs and the removal of the slag heap has been the subject of much controversy ever since. But it could have looked so much worse if it wasn't for Mr Ellis' intervention.

"Tom planted silver birch trees which were the only trees which could grow there - but he got into terrible trouble with the Coal Board," says Ted.

"He was told off in a managers' meeting in front of everyone and told he was wasting money and instead should be concentrating on getting coal out of Bersham.

"A few weeks later Aberfan happened."

In his autobiography, After The Dust Has Setttled, Mr Ellis described how his recommendations were ignored and then frantically accepted in the aftermath of the disaster.

"I decided to remove the top soil and spread it on that part of the tip facing the village of Rhostyllen," wrote Mr Ellis.

"The only reason for doing so was to try and make the tip less ugly for the villagers who looked out on it from their homes.

"We made terraces, spread soil and planted tree saplings."

Mr Ellis goes on to describe how he was called to a meeting after the Aberfan disaster where his superiors take the credit for what he has done.

"The Coal Board director took the credit for what Tom had already done at Bersham," remembers Ted.

"He planted the trees mainly for the villagers to have some green to look at but the roots helped bind the tip together too.

"Tom was there and they were saying 'this is what you have to do' and they took the credit for it.

"All the pits were losing money and were neglected and those tips could have gone at any time.

"They took tips seriously after Aberfan but no-one had ever bothered about them before."

Today Bersham Glenside Ltd owns the landmark Bersham mound, which stands by the A483, and moves are afoot for the six millions tonnes of waste to be flattened.

For many, the 50m high slag heap remains an eyesore but for others it has become an iconic part of the landscape and a monument to the area's industrial heritage.

Perhaps when we pause to reflect on the 144 men, women and children who died 50 years ago, it should act as a monument to them too.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter