The rise of Al Shabaab from the shadows was rather quick, the group rapidly grew from a core of just 33 to a force of more than 5,000 troops in less than four years. Their motivation and main objective at that time was to drive the Ethiopian forces out of the country; of course, that had to be done by a strong insurgency, which Al Shabaab was eager to lead. Though the Ethiopians managed to quell ICU and the AIAI, Al Shabaab, which rose from it ashes, was much more radical and determined in its ideas of implementing Sharia law and some form of an Islamic caliphate/state. Ethiopia's military actions hardened Somalis' religious views and made a fertile ground for spreading extreme religious ideologies, which made recruitment and funding for Al Shabaab much easier. After the withdrawal of Ethiopian forces in 2009, a split occurred in Al Shaabab: two conflicting factions were trying to impose their own views and doctrine on the group. One was led by Sheikh Aweys, a spiritual leader with fundamentally domestic aims, and Sheikh Moktar Ali Zubeyr also known as Godane (educated in Pakistan), who had a more ambitious and extremist agenda, which ultimately prevailed and took control over the group. At that moment, the Al Shabaab agenda changed from nationalistic to a more global and ideological rhetoric, which ended with pledging allegiance to Osama Bin Laden and promoting Al Qaeda's jihad across the horn of Africa.

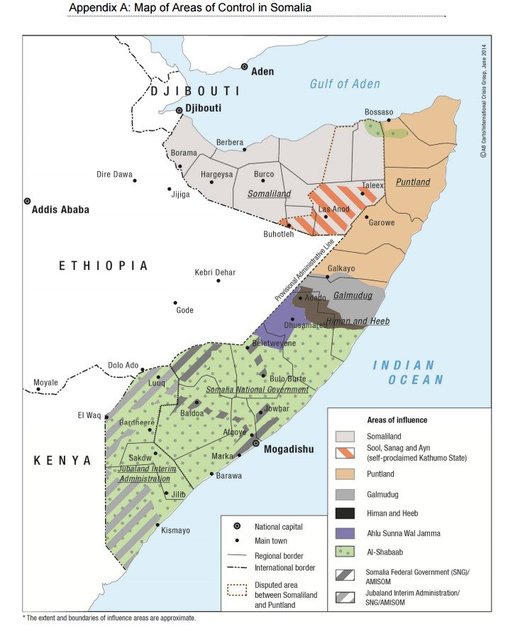

Although Al Shabaab's impact during the past couple of years has decreased, mainly because of new battlefields in Syria and Libya, the group still poses a major threat in the region with the probability of expanding its influence further into the Sahel and also in Yemen. Despite their grievous loss of their leader, Godane in 2014, his successor, Abu Ubaidah, is eager to follow in his footsteps. This can be seen in their constant raids and harassment in Mogadishu targeting primarily non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and United Nations (UN) facilities, extending their reach in Kenya, attracting young fighters and establishing some kind of limited government in some parts of the country which are under Al Shabaab's control.

Before we go any deeper into understanding the structure of Al Shabaab, we first need to determine the doctrine and the ideology behind this radical group. Most of the time, the group is described as a Sunni extremist organisation supplemented with Salafism and Wahhabism. Besides this, Al Shabaab has a strict policy against takfir (bad Muslims), who usually get excommunicated or worse (punishments such as stoning and decapitation are common). The practice of Salafism and Wahhabism is not only used as some kind of ideology, but also as an instrument for attracting funds and finance (there had been rumours that some Gulf states are eager when it comes to funding organisations with this type of doctrine). One of their most important goals is the creation of a fundamentalist Islamic state in the Horn of Africa; it should include not only Somalia but Ethiopia, Kenya and Djibouti as well. Various analysts cite that these radical pan-Islamic ideas come from AIAI, which was a predecessor of Al Shabaab which gave training and needed-knowledge for the future leaders of "the youth". The concept of AIAI, and later ICU, is important in understanding the complex structure of Al Shabaab. Though it is radical and fundamental, it is not monolithic; tribal divides and internal fissures are rather common, especially when more leaders try to take control over the group, differences in their origin and training as well as indoctrination usually leads to conflict between them.

Ahmed Abdi Godane, who triumphed over these internal conflicts in 2011 and 2013, suggests that core group doctrine and affiliation have been settled. Before Godane's victory, the core leadership of Al Shabaab was heterogeneous with strong nationalist and politically pragmatic characters like Hassan Dahir Aweys and Mukhtar Roobow. After the "cleansing" of the leadership, Godane saw a clear future which apparently lies with a strong affiliation with Al Qaeda. After the official pledge to Al Qaeda in 2012, these two organisations began close cooperation with each other in further indoctrination and training of the new recruits. Al Qaeda also played a major role in widening Al Shabaab's vision in terms of globalised jihad rhetoric and propaganda. Implementation of strong Sharia law has become regular; punishments like stoning, decapitation and amputation are common for criminals and also apostates.

Structure, more precisely, the military organisation of Al Shabaab, consists out of five formations/brigades:

- Abu Dalha Al-Sudaani: Lower and Middle Juba

- Sa'ad Bin Mu'aad: Gedo

- Saalah Nabhaan: Bay and Bakool

- Ali Bin Abu Daalib: Banaadir, Lower Shabelle, Middle Shabelle

- Khaalid Bin Wliid: Hiiraan, Mudug, Galgaduud

- Liwaa'ul Qudus: Eastern Sanaag and Bari regions "Sharqistan"

Tactics and strategies which are implemented by Al Shabaab are heavily based on local knowledge and experience from veterans and fighters who participated in former radical organisations in the nineties. This comes as no surprise - many members of Al Shabaab were active during the nineties and especially during the Ethiopian intervention. Also, their expertise in those battles was welcomed by Al Shabaab's leadership in order to train new recruits and improve general combat. A main aspect of the tactics and strategies used by this radical organisation is the asymmetrical warfare, which was executed with wide knowledge and precision. The group was cautious when it came to large-scale battles against larger and better-equipped adversaries, usually they would withdrew their forces in order to reorganise and strike at the right moment. This tactic was further improved by Godane, who decentralised much of the authority within the group making it more flexible and agile.

Commanders or regional "governors" have been appointed, including field commanders who have improved intelligence gathering (Amniyaad), counter-intelligence work, better command of the troops etc. This decentralisation allowed Al Shabaab to easily shift into guerilla warfare style in 2013 and 2014 when the Somali government managed to extend its control over major towns, especially in the south of the country. The jihadists, with their vast knowledge of the region, fled to the countryside and continued their fight. Though they have been driven from some populated areas, there is a growing sense of fear because of the sporadic raids and the retribution, which the terrorists pledged to carry out. Unlike its adversaries, Al Shabaab is quite mobile, which gives it the edge when it comes to fighting in urban areas. Constant raids and pressure, which they keep up thanks to their networks, allows Amniyaad a lot of freedom when conducting assassinations or even suicide attacks. The flow of foreign fighters into the group, especially those from Iraq and Afghanistan, has broadened the knowledge of military and guerilla tactics with a couple of major aspects:

- Extensive use of IEDs and suicide bombers which was not a common sight in Somalia in the past.

- Combat units consist out of nine members, unlike the regular Somali army, which practices with 11 member units, or the Ethiopian army with six member units.

- Heavy emphasis on infantry.

- High mobility of troops due to a limited number of members and a wide area which needs to be covered.

- Distinctive deployment of troops. Al Shabaab usually masses its troops on the borders of the areas which it controls, while there are not many of them in urban areas or city centers. Despite this, the strong psychological effects of fear and retaliation keep citizens in line, who are unable to revolt or oppose their aggressors.

Recruitment and training of Al Shabaab members usually takes place in Somalia and Kenya, but foreign continents like Europe and North America (the US especially) are not the exception. The organisation started as a populist militarist group, focusing on younger parts of the population (staying true to its name, Al Shabaab/"the youth") for mobilisation with constant struggle with the authority of the domestic and foreign factors. With its recruitment programme, Al Shabaab quickly realized that in order to amass new recruits, the idea of waging jihad should be constantly pushed on a daily basis. A regular flow of new recruits needed a population and land from which they could gather them. These factors pushed Al Shabaab to become embedded into the Somali society, as some former members testified (which are often children or teenagers), the organisation gives a mobile phone and a monthly payment of 50 dollars, which for young people in Somalia, seems quite a lot. There are three basic principles on which Al Shabaab recruits its members:

- The use of da'wa [literally means "issuing a summons" or "making an invitation"] gives a strong impact on the youth mainly because they usually lack any deeper religious knowledge. This is often done by various propaganda techniques including videos, books and preaching the importance of jihad.

- Economic motivation also plays a major role. As I mentioned, earlier 50 dollars can mean a lot to a young man in the Somali society. Violence, which is a daily phenomenon in Somalia, makes people used to it and organisations like Al Shabaab largely profit from it. Payment for killing a man can sustain someone's family for a period of time.

- The final part is de-socialisation and re-socialisation of the new recruits. This process can be highly rewarding for the terrorist organisation, since it usually promotes further unification of the new members.

Many of the terrorist or insurgent groups have two main principles of funding which include "lootable" and "unlootable" resources. Those resources may include diamonds, narcotics, gas and similar riches which one territory may possess. Since Al Shabaab lacks this method of funding, the organisation was forced to create an innovative method of gathering financial resources. This new method can be defined as financial control and surveillance of cash flows. This control extends to both domestic and external funding and is directly controlled by the group so it does not rely on third parties. The UN report from 2011 suggests that Al Shabaab was able to collect around 100 million dollars from fees at airports and seaports, taxes on various goods and checkpoints, jihad contributions and extortions justified by religious obligations.

In order to maintain its "taxation" and healthy financial flows, good governance and discipline are essential. In this manner, Al Shabaab has made a wide range of administrative bodies that are far more efficient than the Somali government. These bodies include Maktabatu Maaliya (Ministry of Finance), which has domestic and international responsibilities. On the local level when it comes to gathering taxes, the Amniyat plays a crucial role, while Maktabatu Maaliya is responsible for the macro-economy and development (example: controlling the charcoal exports). These "institutions" give a sense of government and order. For people who live in a state of perpetual chaos these administrative bodies, which were developed by the Al Shabaab, are seen as a more or less good thing; it also helps the organisation maintain its population and recruitment without the use of brutal force. Besides the domestic flow of funds which is reliable and easy to control, there is also an external source of funding. External sources include the Somali diaspora and "deep-pocket" individuals who sympathize with the rhetoric or have other interests in mind when donating financial resources to this group. According to some estimates, 14% of the Somali population lives abroad. These people have certain moral obligations but also relatives who need help back at home. The much-needed help which is delivered from the Somali diaspora sometimes comes to Al Shabaab as well. In the past, especially when the ICU was active, the foreign aid coming from the Somalis living abroad was relatively easy to acquire. Luckily today this type of "foreign aid" is dramatically reduced, mostly due to international actions against those who fund Al Shabaab and domestic prosecutions.

The group also has so-called "deep-pocketed" donors. These donors come from all over the world and when Al Shabaab pledged its allegiance to Al Qaeda, it became much more attractive for these donors. Motivations for donating large amounts of money to terrorist organisations are various and they include: performing a proxy jihad by donating large sums of money to radical organisations, sponsoring those kinds of organisations since the donors themselves cannot be physically present, fight for that organisation or achieve honour for waging a proxy jihad. A 2013 US Treasury Designation Order on Umayr Al-Nuaymi (Qatar businessman) suggests that he allegedly funded Al Shabaab with more than 250,000 dollars. Though Al Shabaab promotes global jihad, it still has donors which support the nationalistic doctrine of the past. Aligning themselves with Al Qaeda (which is strictly orientated to global jihad), there is a probability that some of the donors, domestic and international, who support the nationalistic doctrine, will cut the funds because of this shift in Al Shabaab's goals and doctrine. This was even pointed out by the former leader of Al Qaeda, Osama Bin Laden.

As an organisation, Al Shabaab demonstrated impressive talent for planning, strategy and military tactics, which must not be underestimated. Their social roots in Somalia still remain deep. According to some reports from 2014, the group is still controlling much of the southern part of the country. With the rise of Islamic State and chaos which engulfed much of North Africa and the Middle East, Al Shabaab is positioning itself accordingly, promoting Sharia rule, allaying with Al Qaeda and promoting the idea of an Islamic caliphate. Though the pan-Islamic idea is powerful, with Al Shabaab's rhetoric they retain a strong grip over domestic affairs; this can be seen in their ways of funding via taxes. Despite their rigorous ways of exercising Sharia law in a state such as Somalia, Al Shabaab does not necessarily represent the biggest threat or the biggest problem, hence the absence of any serious uprising from the local population against this organisation. There are also practical benefits provided by the Al Shabaab group, like religious education and some sort of basic institutions and administration. Yet these steps seem insignificant. Looking from abroad, for the locals they can mean a lot. Rooting themselves deep into the sociological sphere and bolstering their relations with the domestic population, it will not be an easy task to remove this radical organisation.

In geopolitical terms, Al Shabaab does not represent a major threat. Unlike the Islamic State and Al Qaeda, it lacks the logistic and foreign support in order to accomplish and spread terror on a global scale. On the other hand, they do represent a major threat in the region; something similar can be observed with Boko Haram. Though they are positioned in the south of the country, Somalia is the Horn of Africa. Somalia has access to the Gulf of Aden, and the proximity to Yemen and the Red Sea can serve not only the interests of Al Shabaab, but also those of foreign organisations which are present in Yemen and maintain contact with Al Shabaab. Al Shabaab's regional influence can also be dangerous because of the instability of the Sahel region. If Al Shabaab manages to use the conflicts in the Middle East and Libya, it can spread further into Sahel. They already have the pattern of Islamic State, which uses different regions and countries in order to avoid total eradication. Thus, dealing with Al Shabaab must be done cautiously. Ethiopian direct military engagement in the past destroyed two radical organisations but also delivered the third one, which is much stronger than its predecessors. Learning from their previous experience is one of the trademarks of Al Shabaab. Directly engaging this organisation may cause unwanted casualties and destruction, which will only strengthen the position of Al Shabaab in the Somali society (we must not forget that Al Shabaab also maintains nationalistic ideas besides global jihad). Thus, the approach must be done through soft power, political reconciliation, mediation support, political and religious education, military support and assistance. Only when the foreign powers realize the realty of Somalis' struggle, can there be hope for a total eradication of radical organisations in that country.

MA IGOR PEJIC, graduated in Political Science from the Foreign Affairs Department at the Faculty of Political Science. He is currently completing an MA in Terrorism, Security and Organised Crime at the University of Belgrade, Serbia.

Comment: The Gulf of Aden is one of the most important trade routes in the world, and one of the West's (e.g., the UK's) biggest geostrategic/economic interests. Somalia's piracy and terrorism problems were practically non-existent while ICU was in charge. But the ICU threatened Western interests in Somalia by exercising autonomy. As Pejic notes, al-Shabaab was not an extremist organization at the beginning. It only became so thanks to infiltration from British terrorist proxies (e.g. recruitment carried out by MI5 asset Omar Bakri's al-Muhajiroun organization). In addition, the SAS had been operating in Somalia for years. Another country successfully divided and conquered, its resources plundered for Western interests. (See T.J. Coles's Britain's Secret Wars for more details.)