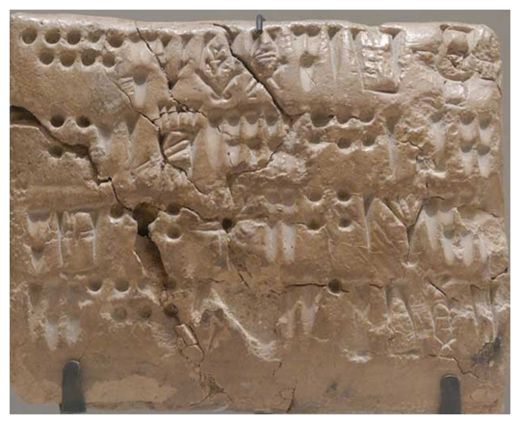

Called proto-Elamite, the writing has its roots in what is now Iran and dates from 3,200 to 3,000 B.C. So far, the 5,000-year-old writing has defied any effort to decode its symbols impressed on clay tablets.

Now a high-tech imaging device developed at the Universities of Oxford and Southampton in England might provide the necessary insight to crack the code once and for all.

Comprising a dome with 76 lights and a camera positioned at the top of the dome, the Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) is able to capture extremely high quality images of ancient documents.

As the object is placed in the center of the dome, 76 photos are taken each with one of the 76 lights individually lit.

The 76 images are then joined in post-processing so that researcher can move the light across the surface of the digital image and use the difference between light and shadow to highlight never before seen details.

"The quality of the images captured is incredible. I have spent the last ten years trying to decipher the proto-Elamite writing system and, with this new technology, I think we are finally on the point of making a breakthrough," Jacob Dahl, from Oxford University's Oriental Studies Faculty, said.

Dahl noted that overlooking differences barely visible to the naked eye may have prevented scholars from deciphering the writing.

"Consider for example not being able to distinguish the letter i from the letter t," he said.

The images are now been made available online for free public access on the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative website.

As high definition images of the clay tablets are shared with scholars around the world, it is hoped that the enigmatic right to left writing will be finally deciphered.

Indeed, a few features of the writing system are already known: the scribes had loaned or possibly shared some signs from or with the Mesopotamians, such as the numerical signs and their systems and symbols for objects like sheep, goats, cereals.

In the past 10 years, Dahl himself has deciphered 1,200 separate signs, but he admits this is almost nothing compared to the complexity of the system.

About 80-90 percent of the signs are maddening puzzle and even basic words as "cow" or "cattle" remain undeciphered.

"Looking at contemporary and later writing systems, we would expect to see proto-Elamite use only symbols to represent things, but we think they also used a syllabary -- for example 'cat' would not be represented by a symbol depicting the animal, but by symbols for the otherwise unrelated words 'ca' and 'at,'" Dahl said.

According to the researcher, half of the signs used in this way seem to have been completely invented for the sounds they represent.

"If this turns out to be the case, it would transform fundamentally how we understand early writing where phonetecism is believed to have been developed through the so-called rebus principle. A modern example would be for example 'I see you,' written with the three signs 'eye,' the 'sea,' and a 'ewe,'" Dahl said.

Containing depictions of animals and mythical creatures, but no representations of the human form whatsoever, the tablets appear to have been used only in administrative and agricultural records.

No evidence has emerged for learning exercises for scribes to improve and preserve the writing.

"The lack of a scholarly tradition meant that a lot of mistakes were made," Dahl said.

Making the decoding even more difficult, the mistakes basically killed the writing system.

Eventually, the proto Elamite became useless even as an administrative system and after some two hundred years it was abandoned.

"This is probably the world's first case of a collapse of knowledge because of the under-funding of education," Dahl said.

After years of study we find it's somebodies grocery list!