Back in July, the Fund said that fiscal consolidation had knocked about 2.5% off UK economic growth. This estimate was based on an assumption that the "fiscal multiplier" - the reduction in GDP growth resulting from a reduction in the government's structural budget deficit - was about 0.5. This estimate was quite similar to that coming out of macroeconomic models like ours at NIESR. It was somewhat larger than the impact estimated by the Office of Budget Responsibility. But it was much smaller that the impacts that many of the most credible macroeconomists - Brad Delong and Paul Krugman in the United States, Martin Wolf and Simon Wren-Lewis here - thought likely. [See Krugman here, for example]. It was also significantly smaller than Dawn Holland here at NIESR and colleagues at LSE suggest in the analysis here.

Now, in a commendable display of self-criticism, the Fund has gone back and reanalysed the forecasts that it made (as well as those made by the OECD and EU). Its conclusion:

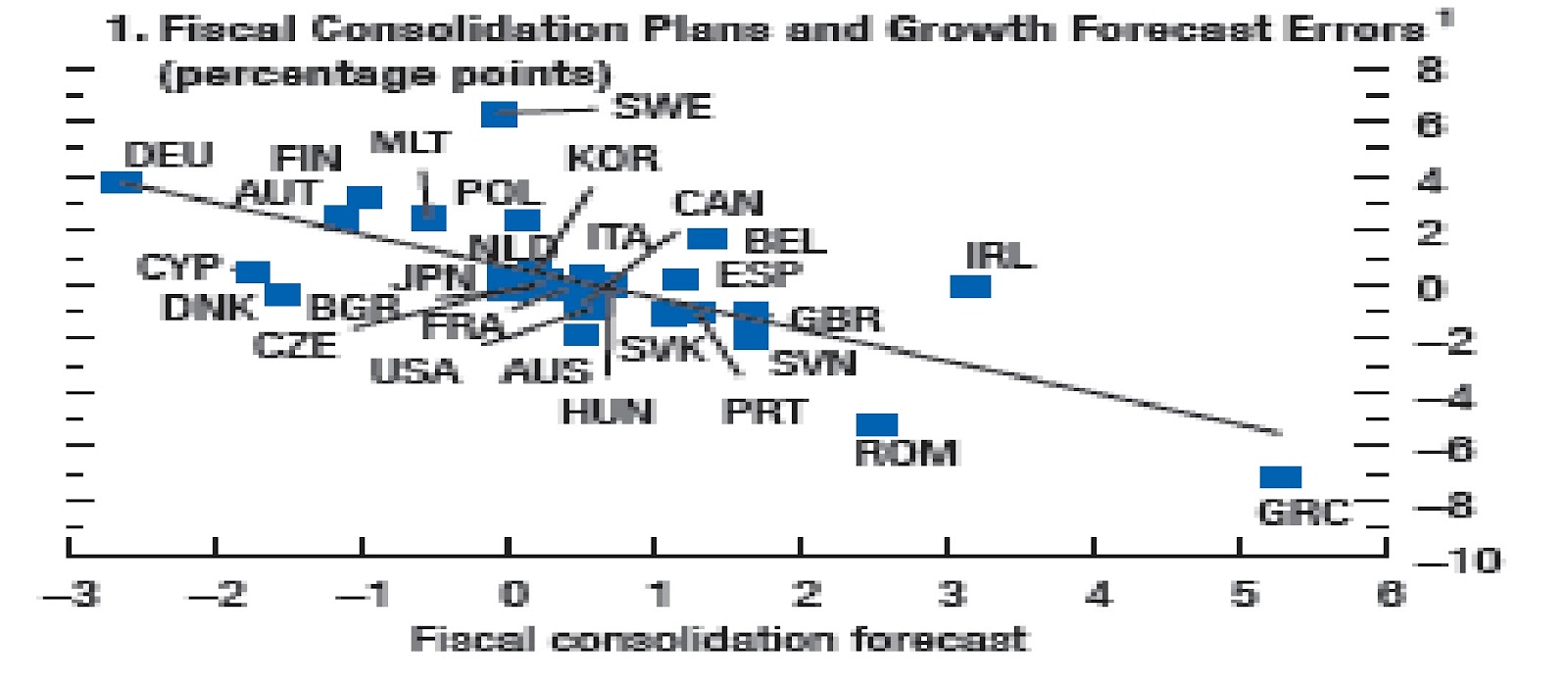

"In line with these assumptions, earlier analysis by the IMF staff suggests that, on average, fiscal multipliers were near 0.5 in advanced economies during the three decades leading up to 2009. If the multipliers underlying the growth forecasts were about 0.5, as this informal evidence suggests, our results indicate that multipliers have actually been in the 0.9 to 1.7 range since the Great Recession. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that in today's environment of substantial economic slack, monetary policy constrained by the zero lower bound, and synchronized fiscal adjustment across numerous economies, multipliers may be well above 1"That is, the Fund is saying: "Delong et. al. were right; we were wrong". They even have a helpful chart, showing that the bigger the fiscal consolidation, the worse growth has been relative to IMF forecasts - implying that the Fund was drastically underestimating the negative impact of fiscal consolidation.

Why does this matter? Everyone agrees growth since 2010 in the UK has been very disappointing. But there has been much debate about why - was it cutting the deficit too quickly, was it the spike in inflation resulting from commodity price rises, was it the impact on confidence from the eurozone? Here at NIESR, we have taken the view that it was a combination of all of these - fiscal policy mistakes made a large contribution, but the other factors mattered too. However, others - notably the OBR, as well as Chris Giles in the FT - have argued that fiscal policy didn't explain much of the weakness in growth. The IMF have now definitively sided with those who think that tightening fiscal policy quickly and sharply had a very large and negative impact.

Once again, the Fund deserve praise for going back, looking at their forecasts, analysing what went wrong, and saying very clearly "We thought the impact of fiscal consolidation on growth would be relatively small. We got it wrong. " Will our government, and those of the eurozone, do the same?

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter