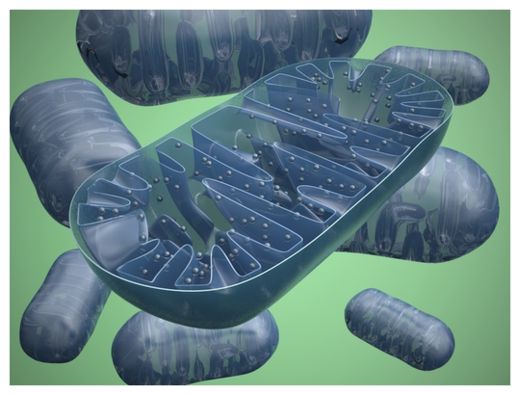

© Wire_man/ShutterstockThe mitochondria are the energy-generating organelles in the cell.

An evolutionary "loophole" might explain why males of many species live shorter lives than their female counterparts, a new study finds.

The loophole lies in the mitochondria, the

energy-generating parts of our cells. The mitochondria have their own DNA, separate from the DNA that resides in the nucleus of the cell that we usually think of when we think of the genome. In almost all species, the mitochondria DNA is passed down solely from mother to child, without input from dad.

This direct line of inheritance may allow harmful mutations to accumulate, according to a new study detailed today (Aug. 2) in the journal

Current Biology. Ordinarily, natural selection helps keep harmful mutations to a minimum by ensuring they're not passed down to offspring. But if a mitochondrial DNA mutation is dangerous only to males and doesn't harm females, there's nothing to stop mom from passing it to her daughters and sons.

"If a mitochondrial mutation pops up that is benign in females, or a mutation pops up that is beneficial to females, this mutation will slip through the gates of

natural selection and go through to the next generation," said study researcher Damian Dowling, an evolutionary biologist at Monash Univeristy in Australia.

The result: a load of mutations that don't harm females, but add up to a

shorter life span for males.

Mother's CurseDowling and his colleague tested this idea - dubbed "Mother's Curse" - in fruit flies (

Drosophila melanogaster). They took flies with standardized nuclear genomes, meaning all had the same cellular DNA, and inserted mitochondrial DNA from 13 different fruit-fly populations around the world.

"The only genetic difference across the strains of flies lay in the origin of the mitochondria," Dowling told LiveScience.

The researchers then recorded how long each strain of flies lived. Their findings revealed a big difference for males, but not for females.

"There was a lot of variation in terms of

male longevity and male aging, but almost no variation in the female parameters of aging," Dowling said. "This provides very strong evidence that there are lots of mutations within the mitochondrial genome that are having an effect on male aging, but are having no effect whatsoever on female aging."

Explaining the gender gapThis finding bolsters the Mother's Curse hypothesis, Dowling said. And the results suggest that the age gap between males and females does not come down to just a few genes.

"In some ways this is bad news for medical biologists, because we're not looking for

the mutation that causes early male aging, we're actually dealing with a whole lot of mutations within this genome that are teaming up to shorten male life span," Dowling said.

The genetic inheritance of mitochondrial DNA is the same across species, so Dowling said he'd expect to see the same results in human males. There is speculation that

women outlive men because men are generally bigger risk-takers or perhaps because testosterone, a hormone men have more of, has deleterious effects on life span, he said. But insects don't have testosterone or a tendency to drive too fast while not wearing a seatbelt, making them a good place to start looking for genetic underpinnings to the gender gap.

Males may not be entirely doomed, however, as evidenced by the fact that

they haven't gone extinct yet. It's possible that the nuclear genome - the DNA we inherit from both of our parents - might be compensating for the mitochondrial handicap in men. In other words, men whose genomes can counteract the nasty effects of mitochondrial mutations might do better and pass on their genes more effectively.

"We're looking to uncover those genes now," Dowling said.

Why do most husbands die first?

Because they want to.