Whilst examining a rural Norfolk church, members of the Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey (NMGS) came across an intriguing inscription etched deeply into one of the pillars of the building. The discovery, made in All Saints church, Litcham, was traditionally thought to be the work of a pilgrim travelling to the important shrine of Walsingham in North Norfolk. However, closer inspection of the inscription using new technology revealed that all was not as it seemed.

The Litcham Cryptogram

"The inscription is known as the Litcham Cryptogram", explained Project Director Matthew Champion, "and has been known about for some decades. Indeed, it was the reason that we chose to carry out one of our first surveys in All Saints. We were interested in looking to see if the church contained further graffiti inscriptions that had not been previously recorded".

The initial survey work soon proved that the Litcham Cryptogram was by no means the only inscription to be found in the church. Within a matter of days the survey had identified over fifty individual images and inscriptions etched into the soft stone pillars of the church. "Almost every pillar was covered with inscriptions", continued Matthew, "and it was clear that there had once been many more. However, our attention kept coming back to the Litcham Cryptogram".

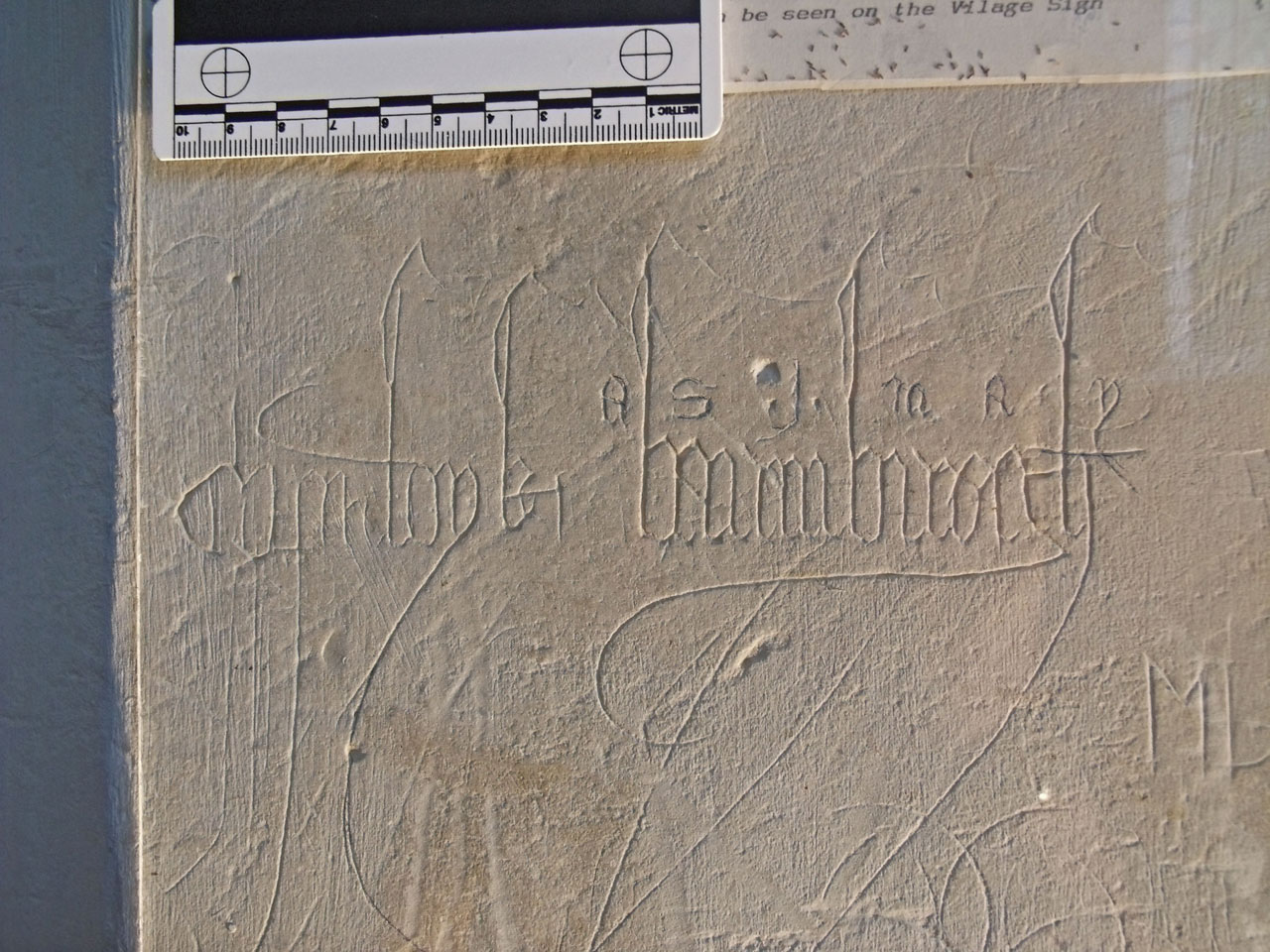

The inscription was etched far deeper into the pillar than much of the surrounding graffiti and it is supposed that this is what had drawn people's attention to it. Indeed, at some point in the past the inscription had actually been placed behind protective Perspex to deter more modern graffiti artists from adding to the original. The inscription itself was written in a very fine medieval 'black-letter' style and was comprised of two lines of text, one above the other.

The traditional translation, which even appeared in the church guidebook, stated that the longer lower line of text was a name, 'Wyke Bamburgh', and that the letters in the upper tier represented the phrase 'Save (my soul) Jesus, Mary and Joseph'. However, upon closer examination, the traditional story soon began to unravel.

Recording a mystery

The NMGS have been pioneering new techniques for quickly recording graffiti inscriptions in the field. In particular the survey utilises digital photography combined with measured raking light images. The results, which are all superimposed to create a complete and scaled image map of the surface, can often show up details that would be invisible using traditional photography or rubbing techniques.

The first images of the cryptogram were very revealing and they were soon convinced that it was not even a cryptogram at all. The images clearly showed that the upper tier of letters were in an entirely different style of text than the lower and were most probably added at a much later date. The cryptogram was, in fact, just one inscription that someone had added to later and, as a result, causing a lot of confusion".

However, the solving of one mystery actually led to the creation of a far deeper mystery, and one that the NMGS has so far been unable to unravel. Having identified the lower inscription as being late medieval, and having examined a vast number of digital images of the text, the survey team soon realised that the traditional translation, of the name 'Wyke Bamburgh', simply didn't fit with what they saw before them.

"It was far more complex than everyone first thought", said Champion," and whilst all the letters that made up the words 'wyke bamburgh' were present, in one form or another, it just didn't make sense. Our images were showing that all the letters were bunched up against each other, with each new letter being created out of the last down stroke of the previous letter. In effect, we have a lot more letters than we first believed, many of them were open to numerous interpretations - and none of them made sense". At a loss to decipher the inscription the NMGS called in the experts.

Investigating over 650 churches

The Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey (NMGS) aims to examine every one of the counties medieval churches, which number over 650, identifying any medieval graffiti and scientifically record it. Although the NMGS has, to date, only completed surveys on around 50 of the counties medieval churches the site examinations have been far more productive than they could have ever imagined. Of the churches examined to date well over half contain significant pre-reformation inscription, most of which have never before been recorded. In addition, the survey members have begun to identify certain geographical and chronological 'hot-spots' that are worthy of study in their own right.

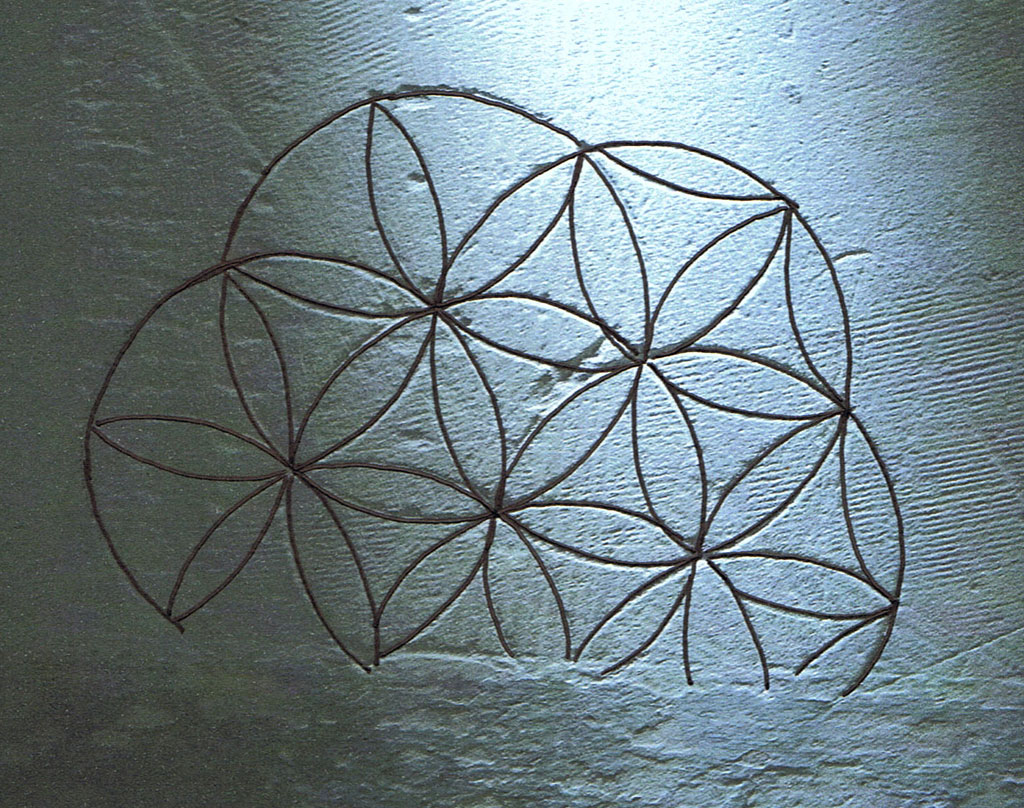

The subject matter of the graffiti inscriptions recorded by the NMGS is as diverse as the churches in which they are located. Certain patterns, such as 'swastika pelta' and 'Daisy wheels', are believed to have religious associations and occur time and time again. However, almost as common are shield shaped pseudo heraldic inscriptions, phallic symbols and multiple crosses.

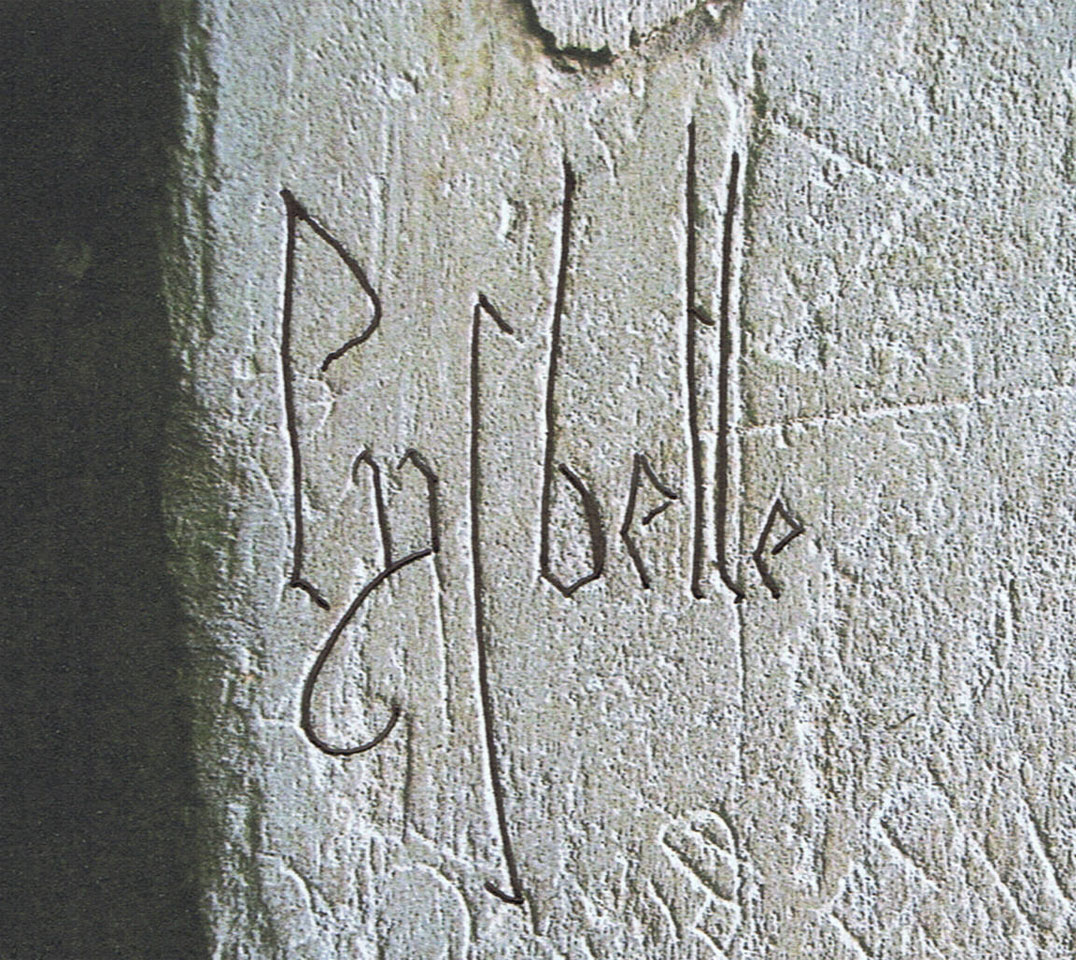

More interesting still are the inscriptions that contain names or prayers, a number of which are in Latin and, in one case, what has tentatively been identified as Greek. These textual inscriptions are often as interesting for the way in which they have been inscribed as for what they actually record. Many of the hands are quite fine, indicating that their creation would have taken a great deal of time, and one particular inscription has the initial letter decorated with streamers and curlicues in imitation of an illuminated manuscript.

Other common inscriptions, that are most probably devotional in nature, are the imprints of hands, feet and complete limbs. Indeed, faces and caricatures have become reasonably common finds during the survey.

However, none of the discoveries made so far are quite as intriguing at the mystery of the Litcham Cryptogram. "Of all the discoveries we have made", concludes Champion, "the Litcham cryptogram is one of the most fascinating. It was created with great effort and patience and was obviously deeply significant to the individual who made it. It was etched into the very fabric of the building with, we must assume, the intention that it would stand as a testament for generations to come. The deep sadness for me is that we are now unable to decipher that meaning".

I can solve this puzzle for ya. It's called "the Flower of LIfe" and represents the sacred geometry and physics behind how life is created and consciousness ascends. It was carved onto the walls in the most ancient of pyramids in Egypt, the Osirion temple at Abydos, and is also underneath the paw of the Lions guarding the entrance to China's forbidden kingdom. Physicist Nassim Harramein did a wonderful lecture on it in layman's terms with beautiful photographs. Here's something to ponder....the same drawing on the Osirion temple was burned into the stone wall with a laser! So the possible reason for this symbol being carved into the wall in this chapel was a symbol for someone "in the know" who has been initiated into the sacred secrets which time eventually lost the interpretation of, although the carving remained behind to benefit the next generation of awakened humans. The Egyptians said they received this knowledge from "The Sun Gods". [Link] [Link] [Link] [Link]