Both in our late 20s, and just starting out in our careers as war correspondents, both of us had already been tear-gassed in angry crowds in the Middle East, travelled with rebel armies in Algeria, and passed checkpoints at night, hoping we would not get shot.

We had both decided we wanted to live a life that was fuelled partially by adrenaline, partially by the desire to report from the worst places on earth, to tell the human story of war.

Bruno was the senior foreign correspondent for France 2, the BBC of France, and I was a foreign correspondent for The Times and Vanity Fair.

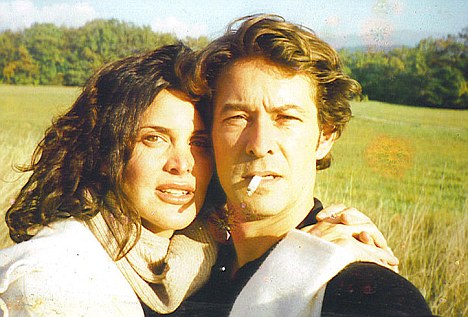

We met when he fell on his knees in front of me in the lobby of the Holiday Inn, the hotel on sniper's alley in Sarajevo where all the journalists lived. That set the tone of the next 17 years of my life - high drama.

He was a polyglot who spoke French, English, German and some Arabic. He climbed the outside of the Eiffel Tower with his camera on his shoulder all the way to the top. He was the most macho man I had ever met and also the most sensitive - the combination was irresistible.

After our time together in Sarajevo, we didn't see each other for five years. He was based in Paris, I was based in London, and we were constantly sent all over the world. We next met in the middle of another war, this time in Algeria. We stayed up all night every night talking, and, of course, drinking.

The difference between us - and this was something I did not discover for a long time - was that he was an alcoholic and I was not.

Maybe I didn't see it because everyone I knew drank. There was huge pressure on me and my colleagues that did not exist in the normal world. We were operating without electricity, water, sometimes without places to sleep - I have spent months living in a tent in Afghanistan.

But there was always the whisky bottle or the bottle of wine smuggled in to dull the senses, help you sleep and blot out the misery, death and disaster we had seen and reported on that day. It seemed quite natural to me that most people I knew ingested enormous amounts of alcohol and then rolled out of bed the next morning with no hangover.

Bruno and I would meet in Paris or London or Africa or the Middle East, collapse into a euphoria of love - and, I'm sorry to say, drink. Except I would stop drinking. And he wouldn't.

Our lives would be something like this: 'Hey, I'm in Thailand on my way on an undercover mission to Burma. Where are you? Liberia? OK, let's meet in Paris in a month.'

It was the stuff of heady, Hollywood romance - and, like the alcohol, the romance was addictive.

Many years and a dozen wars passed between Bruno and I, as well as endless phone calls, three miscarriages, break-ups, a breakdown, and a lot of alcohol.

There was depression, death, suicide of friends, addiction, and more times than I like to think when both of us nearly died. Then came a time when we wanted to live in peace, together.

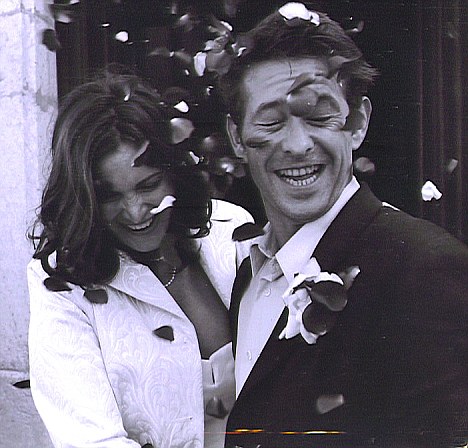

I was 39 when Bruno proposed to me via satellite phone while I was in Somalia. We had been together, more or less, for a decade. 'Let's get married, let's have a baby,' he said, as a gun battle raged outside my hotel room in Mogadishu. He was in Rwanda. 'I don't ever want to lose you.'

We married in 2003 and lived in the Ivory Coast, while civil war raged. Journalists were assassinated, death squads were roaming the streets, the houses near us were burnt down.

I should have noticed, but didn't, how thin Bruno had become, how obsessed he was with working, and how brave - but foolhardy, really - he was when he drove through heavy fire to rescue a friend and her child and take them to the airport.

He had me evacuated, and he stayed on and on. When he called me, he sounded sober - but he was not. He later told me he was drinking whisky in the morning, just to make it through the terror of the day: the road blocks, the mass graves, the dead bodies.

This was when he started to drink to numb the fear, the pain when his friends started getting killed, and the fact he was scared.

But he never talked about it. He kept all the bad stuff to himself. His mission in life was to protect me.

I was the girl with the broken wing, and he saw me as someone fragile, someone who needed looking after, someone who wandered too often into dangerous places alone and needed someone to come charging in like Superman to rescue me. He always wanted to save me.

So who's the addict here? Maybe I was addicted to romance, at least this high-octane cinematic romance of a man barging through a door, coming from a war zone, laden with exotic gifts: precious stones from Madagascar, where he had been beaten up during a riot; a silk evening gown from a clandestine mission filming child slaves in Burma; an enormous diamond from South Africa after he had worked undercover in Zimbabwe.

After a romance like this, how could I go back to normal life? Try going out with an accountant after that.

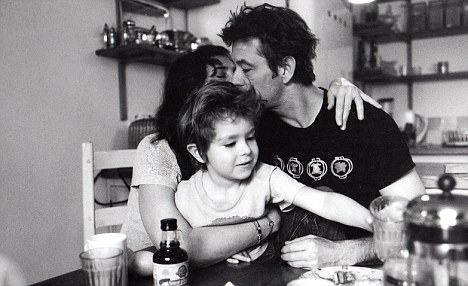

In the winter of 2004, we settled in Paris and had a son, Luca. Bruno was the most amazing father I had ever seen. But he was drinking every single night and not sleeping, and sinking into a hopeless depression, the result of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

There were always empty wine bottles on the table, by the bins. One day, we took Luca into a small grocery store and he pointed to some bottles of wine and said: 'Daddy!'

One afternoon, when Luca was two years old, I took a phone call from a doctor. She explained that she worked at Val de Grace, the military hospital known for treating Yasser Arafat and Jacques Chirac, and that she was a doctor treating my husband.

'I wanted to tell you that I am here with your husband and I am keeping him here under orders for several weeks,' she said. She explained it was her belief that he was exhausted and suicidal.

I held the phone and sat down in the nearest chair. All I knew was that Bruno had left the house that morning for a check-up. 'He's not suicidal,' I said, trying to find the words. 'He's just tired.'

There was a lingering pause.

'May I speak to him?' I said. She passed the phone to Bruno. He got on, his voice full of tears. 'Do you want to stay there?' I said as gently as I could. 'I'm so tired,' he said. 'I'm sorry.'

I sat at the desk thinking of Bruno in the hospital, alone, tired, scared. I thought of how much responsibility he had taken on, so quickly after coming back from Africa. A pregnant, demanding wife. A new city. A premature baby.

'My shoulders aren't that big,' I remembered him once telling me. He came home within a few weeks, but he was never really the same again. The ghosts of the past were chasing us. And they had managed to catch him.

'Inside I feel like ashes,' he said.

'Do you think,' I asked Bruno late one night. 'That this stuff really messed us up for good?'

'What stuff?'

'All of it. The graves, the fires, the bombs. All of it.'

He did not say anything for a while. He poured more wine.

'Did it hurt us?'

After a while, he finally answered me. 'How could it not?'

His drinking got worse and worse, but there were glimmers of hope. The same courage that kept him alive in war zones all those years sent him to Alcoholic Anonymous and he began doing their famous 12-step programme.

It was not easy - and I knew how much he suffered. It was also painful for me not to be able to help and to know he didn't want my help.

I went to an AA Christmas party, and while everyone was friendly and welcoming, it was clear they set a wall between 'us and them'.

Like many wives living with alcoholic husbands, I was not an addict or an alcoholic and, therefore, I was an outsider. I could never understand their suffering, their pain. Bruno changed, too. While he stayed sober, he stopped seeing our friends and he stopped socialising with the world that was not AA.

People were either 'my cult' as he jokingly called them or 'not my cult'.

By that he meant non-alcoholics - meaning me.

It was a no-win situation - I wanted desperately for my husband to survive and be sober, but I did not want to lose him to the smelly hall of The American Church on Quai d'Orsay where he seemed to enter another world. The world of AA.

I met a lovely woman at an AA party who spelt it out for me. 'It's amazing that you guys are still together,' she said. 'Most people who get sober find it impossible to carry on with the relationship they had while they were drinking.'

A light bulb went on as I realised we were barely hanging on.

In some ways I hate AA, because it stole my husband from me. I bought every book I could find on alcoholism and spouses of alcoholics. I went to Al Anon, the support group for loved ones of alcoholics, and hated it.

It met in a church on a Saturday afternoon. The people argued about who made the tea and who cleaned up. When I tried to talk, a stern woman kept interrupting me.

'You have to say, hello, my name is Janine and I am the spouse of an alcoholic,' she kept repeating in a robotic voice.

So I said it, and every time, the group would say, 'Welcome Janine!' like happy morons, and it was too weird. I fled in tears halfway through.

My friends begged me to go back, that I needed support. But I just didn't feel comfortable with the concept. It treated us all like victims; my whole spirit rebelled against being a victim.

Bruno and I separated, but there never was a clean break in the way that people divorce.

We loved each other, as fiercely as on the day when we had put wedding rings on our fingers. That had not changed.

There was no fighting over money or Luca because both of us had a common goal - to raise this beautiful little boy in the best way we could.

But we simply could not live together, because when people do get sober, they change radically.

Bruno took a studio around the corner, and now comes over every day, sometimes twice a day. As I write this, he is here, having just taken Luca to school.

How do you amputate the love of your life from your world?

You don't. It is painful beyond belief, but there are ways of triumphing. Most of all, there is his triumph. My husband is more than three years sober.

There are days when I yearn for the wild husband I had, the days when we lived in Africa and drank shots, and he jumped on top of the bar and ran down it to where I was sitting just to kiss me.

Or the nights we went dancing, met on helicopters and airports in Afghanistan, Benin, Nairobi, Los Angeles, and many other places.

I miss it all. But I am also grateful he is alive. And recovered.

Oh boy. No way is AA a cult in any respect at all, however if you wish to save your life and stop drinking it is bloody stupid to remain with someone who is drinking heavily or you have done a lot of out of order drinking with. The bottom line is death, and an alcoholic death is a pretty horrendous one. In my twenty eight years in AA I have seen fire deaths, falling downstairs deaths, car deaths, exploding insides deaths (when you heamorage your stomach out through mouth and nose and your entire blood system follows) and liver failure deaths. In getting sober and well again we all have to take a good look at our lives. Al anon is a related group for relations of alcoholics so no-one need feel left out, and alcoholics, I can assure you, do not feel superior to "normal" people. Of course alcoholics change in AA, that is the whole point.