© unknown

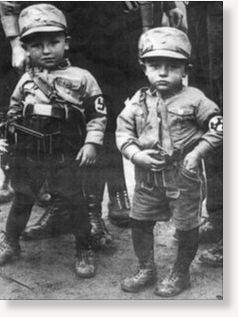

© unknownInge uses this picture of two boys in her lessons on moral choice

She shows the class a photograph of two young boys - they can barely be 10 - who pose in Nazi regalia, and she seeks reaction. One has his chest puffed out in pride, the other seems reluctant and shame-faced. It is for today's children to decide which they would rather be.

If the school visit goes well, she says, a child will say that he or she is going home to ask the parents and grandparents what happened in the war in their family. It makes Inge feel that she has set people thinking and asking.

She was spurred to this mission by her own past, a past hidden in a suitcase - and her mother's mind.

She was only two when her father died in the Siege of Leningrad, so she never knew him, or knew him only through the letters that her mother would read to her on Sundays.

"She said, 'Come, sit down. I will read some parts of father's letter. You should know him because he is not here and you can't see what a wonderful man he was'."

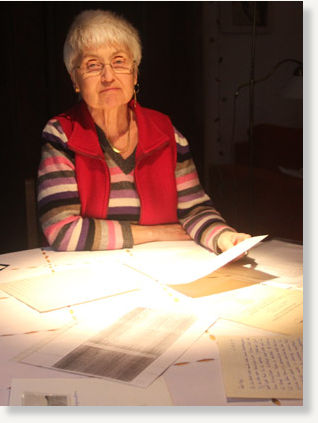

Letters from the frontBut Inge the child noticed gaps, sections that her mother skipped over, and those gaps nagged her for decades into adulthood. At the age of 40, she asked her mother if she could read the letters in full.

What she discovered was that the gaps were detailed descriptions of bad events in which her father seemed to be implicated. He was a committed Nazi who joined the party in 1933 and an officer on the Russian front, and he had clearly been involved in terrible things.

Inge was 40 when she read letters detailing her father's activities during the war

"More than 30 partisans are hanging on the trees," one letter said. There was a sense of pride in his letters at the might of the German war machine.

"I phoned my mother and she said, 'Oh Inge. I didn't want you to read this because it was terrible'."

Over the years, Inge's mother, herself, had undergone a rebirth. When war broke out, she and her husband were both staunch Nazis, and when her husband died she had grieved with pride.

"My mother was a proud widow because she was widow for the Fuhrer, for the leader, for Hitler," says Inge.

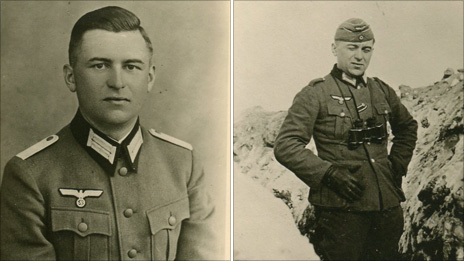

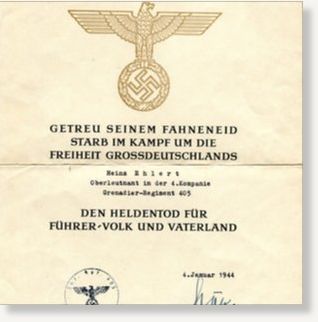

She had a certificate from the Nazi authorities telling her that her husband had died "in the struggle for the freedom of Greater Germany". She kept photographs of him taken in uniform on the Russian front, his chest puffed out in pride.

And, then, with total defeat, she found she had lost everything - her home, her husband and her ideology.

And shame gradually came to her, helped by her daughter, so when Inge asked her about the events in the letters, her mother was very ashamed.

Jewish connectionsThe discovery prompted Inge to help the descendants of Holocaust survivors and victims to find their history, and also to talk in schools.

"When I started to make connections with Jews in Germany and elsewhere, my mother said, 'You are doing this for me, too'."

Throughout Germany, there are people like Inge, seeking out the painful past - tending cemeteries and synagogues, creating museums, simply documenting.

© unknownInge's mother was initially proud of her husband who died in the Siege of Leningrad

Arthur Obermayer, who is Jewish, used to visit Southern Germany with his wife to trace their families' pasts.

"In every town, we found people who on a volunteer basis were preserving Jewish history and culture," he says.

"And they were doing it just because they felt that as Germans it was the right thing to do, because they felt that there was no other constructive way they could respond to Germany's horrible past."

Inge has called a family meeting for this summer. "In my family it was a long time before we could talk about the family history because a lot of the family have been Nazis," she says.

Will it be an easy, amicable meeting? "No," she roared. "People my age say: 'Why are we talking about it? Everybody knows what happened in the family'. And then the next generation says, 'Father, you never told me. I knew nothing about the family background'.

"But now they can come. They can listen. They can read a lot of letters and documents.

"And people are coming. Young people are coming".

It should be said that Arthur Obermayer feels great hope for Germany. Inge, too, says that much is being done. A past is being confronted - painfully.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter